What Does Cultivated Meat Actually Taste Like? We Asked People Who’ve Tried the Real Thing

8 Mins Read

With a number of cultivated meat startups hosting public tastings of their products, three taste testers take us behind the scenes of what it’s like to bite into the future from cultivated fois gras to cell-cultured salmon.

It was a typically humid day in Singapore, with some scattered rain bringing respite from the heat. Danai Georgiadou hopped on Grab – aka Uber for the city-state – in search of a comforting Sunday lunch.

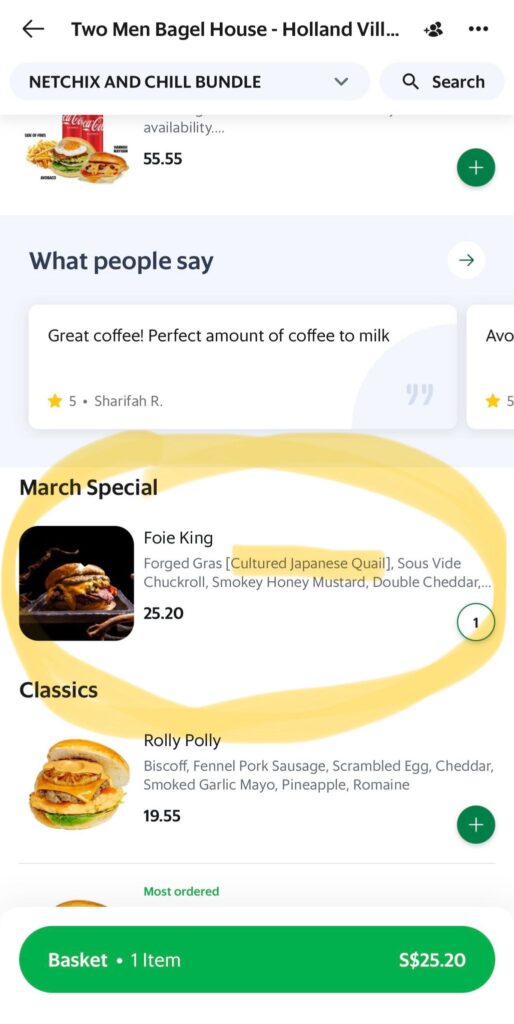

Navigating through the options, she landed on Two Men Bagel House, one of several restaurants that have partnered with Vow, the Australian startup behind cultured quail and foie gras.

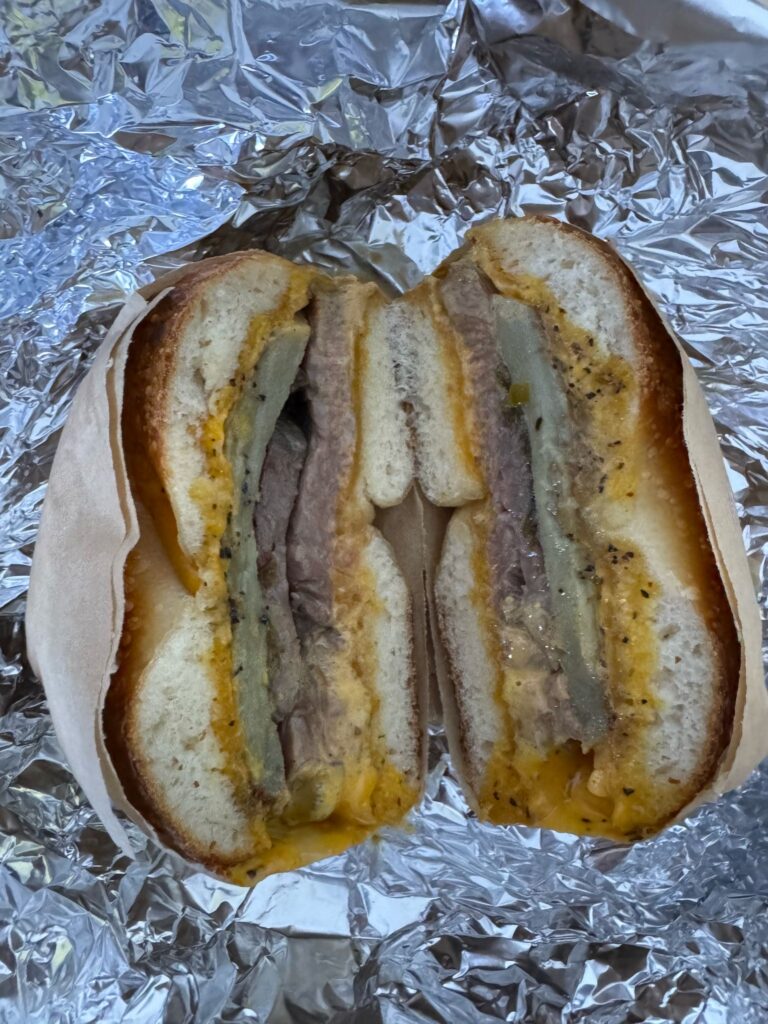

She opted for the Foie King, an S$25.20 ($19) bagel featuring the Forged Gras – as it is branded – combined with sous-vide beef skirt steak, jalapeño relish, smokey honey mustard, and double Cheddar.

Georgiadou is – as you might have guessed – a meat-eater; as a stem cell scientist and member of Cellular Agriculture Greece, she is at the heart of the future food movement. She’s part of a small but growing group of people who have tasted cultivated meat.

“What stood out to me was that it was genuinely delicious,” she says of Vow’s foie gras. The bagel delivered to her doorstep wasn’t the first time she had tasted it. Georgiadou has previously enjoyed the company’s cultivated meat at Tipping Club, Ryan Clift’s pioneering gastro-cocktail establishment, before it closed in 2024.

She paid S$250 ($187) for a set dinner menu, and S$150 ($112) for a lunch menu, both featuring Vow. “I’ve tried Forged Gras in many forms/dishes by Ryan Clift. Croquettes, covered in solid duck butter, fluffy texture like whipped cream. In the bagel I got as takeout, it was grilled,” she says.

“The chefs managed to create some amazing dishes with it. I’ll admit, I’m a bit biased since I work in the field and advocate for cultivated meat, but I really enjoyed it. I’d say Forged Gras has a very versatile texture, which gives you the flexibility to cook it in many different ways.”

Tasting Wildtype’s cultivated salmon: ‘Better than conventional lox’

On the other side of the world, Brian Cooley was in Marin County, California, attending a pop-up event at Loveski Deli. It was hosted by Wildtype, a San Francisco-based startup working to commercialise cultivated seafood.

“I learned about the pop-up by being on a Wildtype waitlist to try their product,” says Cooley, a technology expert who spent nearly three decades as CNET’s tech editor. “A stream of people like me arrived and ordered Wildtype lox on a bagel from a special one-day menu, and we all paid for our orders (about $24 for a bagel with lox as I recall).”

So, the million-dollar question: did it live up to the ‘real thing’? “You would have to tell someone that the Wildtype lox wasn’t conventional for them to suspect it was anything different,” says Cooley. “That’s the crucial bar to clear for any alt-protein.”

He adds: “I think it’s actually better than conventional lox because it doesn’t have the occasional gristle or silverskin you find in conventional products.”

Mission Barns’s cultivated bacon ‘tastes just like it should’

Gustaf Brandberg, founding partner at Swedish VC firm Gullspång Invest, is an investor in Mission Barns. The cultivated pork fat maker recently earned a ‘no questions’ letter from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) – the first for a cultivated meat company since 2023 – and aims to launch its products into restaurants and supermarkets later this year.

“I have tried Mission Barns’s products for several years, and one of the main reasons we invested in the company is the quality of the products,” says Brandberg. “The bacon tastes just like bacon should, and the meatballs and salami could trick just anyone into thinking that they are made of meat, not a hybrid product with pork fat in an otherwise plant-based product.”

Fat, he says, is the key element: “A lot of the taste is carried through the fat, so what stands out compared to other plant-based alternatives is how closely it mimics meat.”

Where can cultivated meat improve?

Okay, so cultivated meat has the same – or even – better sensory qualities than the products it’s aiming to replace. Where is it lacking?

Brandberg, understandably, passed on that question. For Georgiadou’s palate, however, the cultured foie gras was a touch salty. “But that’s just personal preference,” she says.

“The fact that Forged Gras contains 51% cultivated quail is already incredible, especially considering how expensive it is to produce any cultivated meat product. If there’s one area for improvement – and I’m confident it will get there – it would be increasing the cultivated meat content.”

As Cooley attested to, the texture of the Wildtype salmon was ideal for him. “But some other tasters mentioned that it was slightly ‘softer’ than conventional lox,” he recalls.

“It also didn’t smell ‘fishy’, which some people might miss,” he adds. “But when you understand why conventional seafood smells fishy, you don’t miss that ever again.”

Cultivated meat is like most tech products

So if cultivated meat tastes so good, what’s stopping it from appearing on our plates? Well, policymakers, for starters – one country and two US states have banned cultivated meat from being sold, with others on the horizon.

Investors are stepping away from the sector, with funding falling by 75% in 2023, followed by another 40% drop in 2024, reaching just $137M. “I’m not surprised that investors and consumers, for different reasons, are going through phases of the Gartner Hype Cycle with regards to alt-proteins,” says Cooley.

“But alt-protein isn’t one sector: We have a solid sector of plant-based meats, the imminent launch of cultivated meats – Wildtype being one example – and the development of interesting new fermented products, especially in the alt-dairy category.”

These three product groups have room to grow and take repeated “bites at the apple” of consumer acceptance, just like most tech products whose path was rocky before they became ubiquitous. “I’m also reminded of Rosabeth Moss-Kanter’s maxim that many big ideas seem like a failure in the middle, and Roy Amara’s observation that we tend to overestimate a technology’s impact early and underestimate its impact later,” he says.

“Yes, food is very different from VR or AI, but both must work from the playbook of getting people to accept unfamiliar manners and methods of doing things to live better tomorrow than today.”

The ‘right players’ have survived, and things will ‘only go up’

For Georgiadou, the shift in the cultivated meat landscape was much needed. “When I joined the research front of cultivated meat in Singapore in 2022, funding was flowing, driven by overpromises, unfeasible milestones, and dream-like deliverables pitched to investors. There were many founders who just wanted to join in the hype without actually having a solid scientific foundation or proper planning,” she suggests.

“As a researcher in the public sector, I experienced that firsthand – I was contacted by many of them for scientific advice. So, as we all saw, there was a big drop in the years that followed. Companies went bankrupt or got acquired, simply because they couldn’t meet those unrealistic promises. This not only led to a loss of investor trust, but has also hurt the cultivated meat field overall.

“But, because of that drop, I can now see that the right players survived, and anyone stepping in now knows they need to be ready for a fight. Expectations have also been reset. Cultivated meat isn’t just another alternative protein – it’s a novel food, a new technology. So the investors coming in now are better prepared, with more realistic expectations.”

Brandberg explains that the FDA approval for Mission Barns took much longer than he believed when his firm invested. “It’s good that the FDA is diligent when approving new food production methods, but we hope they can speed up their processes. After all, the end product is normal pork fat, produced in a bioreactor and not in a living creature,” he says.

“The slow approval processes have hampered the whole industry, and cultivated companies still need to prove that they can produce ingredients at scale cost-efficiently. This is where we think cultivated fat has an advantage over cultivated meat; you only need a few percentages of fat in the end product, dramatically reducing the cost of ingredients.”

Georgiadou is “pretty confident” that things will now “only go up” for cultivated meat. “And when it comes to political challenges – anything new always causes waves in the beginning. IVF (in vitro fertilisation) faced huge political and ethical resistance when it first emerged, but today it’s one of the most common reproductive assistance procedures,” she says.

“Why wouldn’t the same happen with cultivated meat? History always repeats itself.”