7 Mins Read

Ahead of COP28, new FAO reports will advise rich nations to cut their meat intake, especially given that their actions disproportionally affect lives in developing countries.

The UN will host COP28 starting this week in Dubai, and with this year’s climate summit poised to increase its focus on food systems, the FAO is set to unveil a food and agriculture roadmap to meet the 1.5°C target.

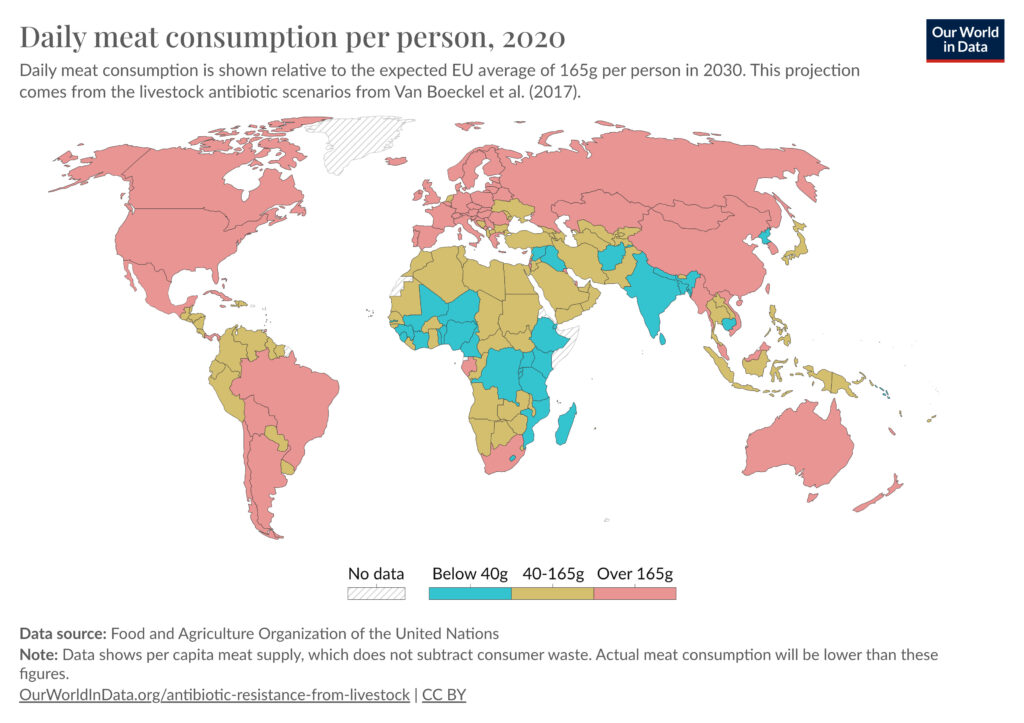

It’s a pretty well-known fact that rich countries eat too much meat. In the US, people consume 127kg of meat per year, while in Australia, that figure stands at 120kg. Canadians eat 90kg each year, and Spaniards consume 100kg.

According to the Eat-Lancet Commission, we should limit our annual meat intake to 15.7kg to keep in line with our climate goals – this means meat consumption is around eight times higher than the recommended amount in the US and Australia, and over six times more in Canada and Spain.

In contrast, many developing nations tend to eat much less meat – for example, 7kg per year in Nigeria, 3kg in the Democratic Republic of Congo. We also know that food systems account for a third of all greenhouse gas emissions and that meat makes up 60% of total food emissions. The problem, then, is one of inequality – the Global North is responsible for 92% of our excess emissions, but 91% of all deaths related to extreme weather occur in developing countries, which are mostly in the Global South.

An Oxfam report earlier this month highlighted this gap – explaining how high-income countries (mostly in the Global North) contributed to 40% of all consumption-based carbon emissions in 2019, and low-income nations (mostly in the Global South) made up just 0.4%. In fact, Oxfam estimated that it would take 1,500 years for someone in the bottom 99% to produce as many emissions as the richest 1% do in a single year.

It’s the marginalised communities that suffer most – migrants, women, girls, Indigenous populations, and those who live in extreme poverty and/or live and work in extreme weather are more financially and physically susceptible to floods, drought, heatwaves and forest fires. “The super-rich are plundering and polluting the planet to the point of destruction and it is those who can least afford it who are paying the highest price,” said Chiara Liguori, senior climate justice policy advisor at Oxfam.

What the FAO roadmap at COP28 will include

With this – and the fact that we’re actually on course to reach 3°C of temperature rises above pre-industrial levels – in mind, COP28 couldn’t come soon enough. It has already been announced that this year’s conference will, at long last, focus on food systems (including a dedicated agri-food day on December 10th), as we look to meet the increasingly unrealistic 1.5°C goal.

Now, Bloomberg reports that the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) – which will be presenting a first-of-its-kind roadmap for the agrifood sector’s path to 1.5°C – will highlight the overconsumption of meat by the rich, as well as the impact of the livestock industry at COP28.

Countries that eat too much meat will be advised to cut back, and developing nations will need to improve their animal agriculture industry. While these recommendations will be non-binding, the roadmap will likely inform policy and funding decisions, and provide a much-needed jolt to the food sector’s climate action.

In terms of the guidance on meat, it’s intended to be a clear message to governments – especially politicians in richer countries, who shy away from consumer behaviour-shaping policies, particularly those that ask them to reduce consumption of daily items.

“Livestock is politically sensitive, but we need to deal with sensitive issues to solve the problem,” Dhanush Dinesh, founder of Dutch food non-profit Clim-Eat, told the publication. “If we don’t tackle the livestock problem, we are not going to solve climate change. The key problem is overconsumption.”

The FAO is hoping to balance climate transition with food security for an increasingly populated planet. In addition to asking rich people and countries to eat less meat, its roadmap will encourage farmers in developing countries to boost the productivity of their livestock and supply more sustainably.

Additionally, the plan – which will be rolled out in three parts over the next few years, alongside country-specific recommendations – will touch upon how producers will adapt to changing and unpredictable weather patterns to tackle food waste, post-harvest loss, and fertiliser use. Farmers around the world are experiencing poor harvests and crop failures – from tomatoes and peaches to potatoes and oranges – due to climate change events.

“This roadmap is needed to bring clarity to both companies and investors so that they can plan for the transition,” Sofía Condés, head of investor outreach at FAIRR Initiative, told Bloomberg. “The longer companies wait to act, the more drastic and potentially disruptive the transition.”

Dinesh added that while previous climate summits have kept away from food and agriculture issues owing to sensitivity around food security, this year, the UN is aiming to introduce several initiatives outside formal talks: “I see more people coming, more events, more activities around food systems.”

Controversies abound, can COP28 deliver?

This idea of informal discussions is more relevant than ever, with the BBC reporting that the UAE planned to use its position as COP28 host to strike oil and gas deals with 15 countries, with the host nation responding by saying “private meetings are private”. It doesn’t paint a great picture for a country that has the world’s third-largest net-zero-busting plans for oil and gas expansion, and whose new fossil fuel developments are incompatible with the 2050 net-zero goals.

The COP28 president Dr Sultan Al Jaber, meanwhile, is the CEO of Adnoc, the UAE national oil company, which the Guardian found hasn’t disclosed its emissions or published a sustainability report since 2016 (though it’s currently conducting studies).

But the hosts aren’t the only body mired in controversy. The FAO itself was subject to an investigation that revealed it censored and undermined work by its own officials on the methane emissions caused by the animal agriculture industry, following pressure from livestock lobby groups. “Even if livestock contributes 18% to climate change, the FAO shall not say that,” its livestock analysis head recalled being told by a senior in 2009. “It’s not in the interest of the FAO to highlight environmental impacts.”

There are also concerns about the continued decline of the FAO’s estimate of livestock methane emissions, which was calculated to be 18% in 2006, then changed to 14.5% in 2013, and is now cited at 11.2%. Other research puts this number at 20% or between 16.5-28.1%. And one study explained that the FAO’s use of modelling over verifiable monitoring data could underestimate these methane emissions by the livestock industry by up to 90% in countries like the US.

The FAO has a lot to contend with and will be hoping it can stitch up its reputation with a strong showing at the food-centric COP28. The summit will host its first-ever Food, Agriculture and Water Day on December 10, which will highlight investment in innovation, procurement around regenerative agriculture, national transformation pathways underpinned by financing mechanisms, and project preparation.

Moreover, COP28 will host the second edition of the Food4Climate Pavilion, convening a coalition of NGOs to highlight the importance of prioritising the production of alternative proteins (two-thirds of the summit’s menu will be meatless) and – the FAO roadmap – tackle the overconsumption of meat in the Global North.

In fact, this North-South divide was prevalent at Glasgow’s COP26, when thousands from the Global South couldn’t attend the conference due to visa and accreditation issues, lack of access to Covid-19 vaccines, and changing travel rules. Addressing this climate inequality is absolutely crucial – if global temperatures rise by 2°C, the richest humans (the ones who eat the most meat too) would be primarily responsible for the climate-induced deaths of low-income people.

Can the COP28 stakeholders address the controversies and deliver a concrete, achievable climate action plan? The world will be watching.