3 Mins Read

As world leaders gathered at COP26 to draw up plans to tackle climate change, one big thing was missing from the agenda: food. With the global food system accounting for nearly a third of emissions, experts say that bringing food and agriculture into climate talks will be “critical” to meet the 1.5℃ under the Paris agreement.

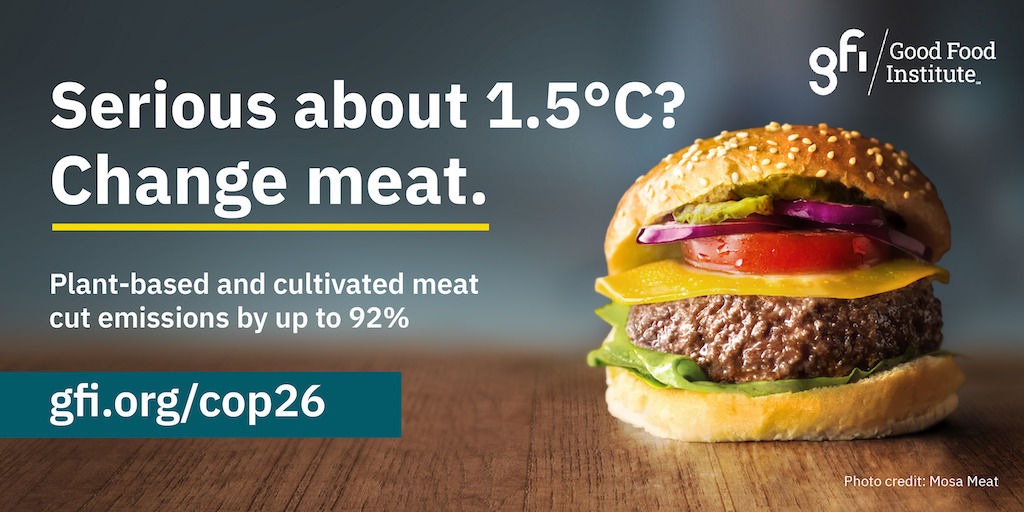

World leaders gathered at COP26 over the last two weeks to discuss their climate action plans, but the absence of food emissions from the agenda will hamper progress on cutting emissions. Experts from the Good Food Institute (GFI) recently issued a warning that the lack of discussion about food and agriculture, especially carbon-intensive livestock farming, will make it “impossible” to meet the 1.5℃ target.

Food system emissions

“Under-represented on the agenda is food and agriculture, particularly looking at meat consumption in ways that limit world temperature rise to the critical 1.5ºC target,” says Alice Ravenscroft, who manages GFI Europe’s policy team.

Scientists have already emphasised the crucial need to tackle emissions from livestock farming, which accounts for the majority of agricultural emissions. Globally, animal agriculture represents nearly a fifth of GHGs, more than all types of transportation combined.

A landmark study published last year warned that the Paris climate goals remain “out of reach” if drastic measures weren’t taken to combat emissions from meat and dairy production, even if fossil fuels were to be eradicated immediately.

Just last week, the Climate Action Tracker’s annual report says that current pledges made at COP26, including the new deforestation and methane agreements, will still lead to 2.4℃ of global heating.

“Too few are zeroing in on the significant role that agriculture and our global food system must play in achieving [carbon] reductions,” Ravenscroft says. “Meeting the 1.5ºC target requires rapid and ambitious changes to food systems, including how meat is made.”

Focus on alternative proteins

One of the ways that governments can assist in a “meaningful transition” towards a sustainable food system is investing in alternative proteins, given the enormous environmental cost of current meat and dairy production.

According to the latest Meat Atlas report, just five of the world’s biggest meat and dairy firms together drive more emissions than big oil firms like Exxon or BP. Despite this, climate negotiations have primarily focused on fossil fuels and renewable energy technologies, with little attention paid to the potential of alternative proteins to curb emissions.

“Just as they did with renewable energy, governments now need to step up and invest money into sustainable protein research and development, as part of their national climate plans,” urged Ravenscroft. “This level of official recognition will also encourage essential investment into the rapidly growing cultivated and plant-based meat innovation ecosystem taking shape across the public and private sectors.”

Two separate reports published recently, one from the GFI and the other from PwC, Rabobank and Temasek, have called for greater public support for the alternative protein industry as part of climate action. Most of the funding to date flowing into alternative proteins have come from the private sector, with public financing making up just 1% of the record $3.1 billion invested in 2020.

Much of the funding to date for the industry has come from the private sector, with 2020 being a record year that saw investment triple to $3.1 billion. Public financing in the same year stood at just 1% of that figure.

“Alternative proteins need to be on the table, placed at the very centre of national and international policies to reduce our emissions,” commented Revenscroft. “They should not be an afterthought.”

Lead image courtesy of Unsplash.