Some of the Most Powerful Ad & PR Execs Have Links to Highly Polluting Industries: Report

6 Mins Read

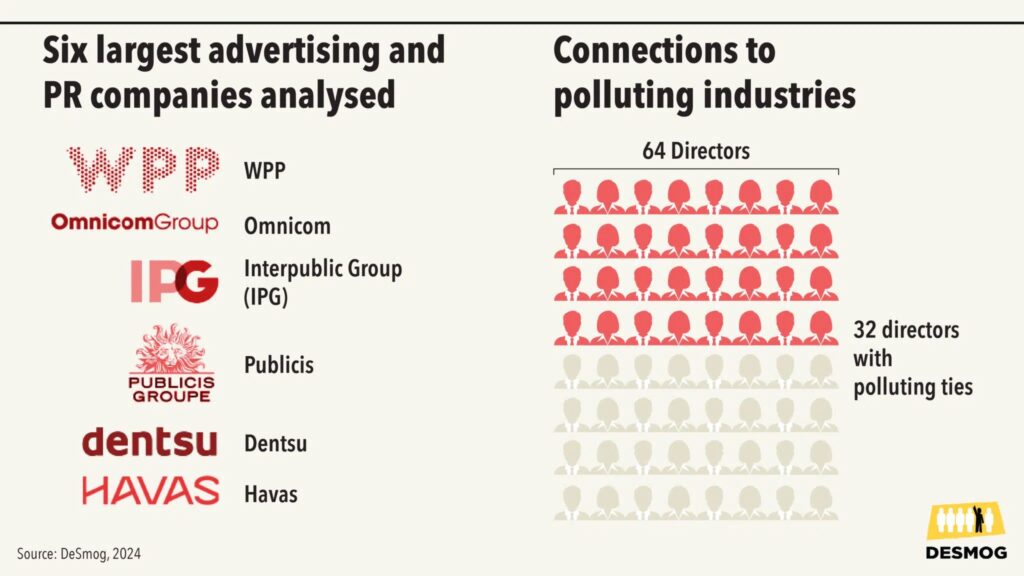

Half of the executives at the six largest advertising and public relations firms have connections with heavily polluting industries, according to a new investigation by climate media outlet DeSmog and marketing activism group Clean Creatives.

The PR industry has its own PR problem: climate change.

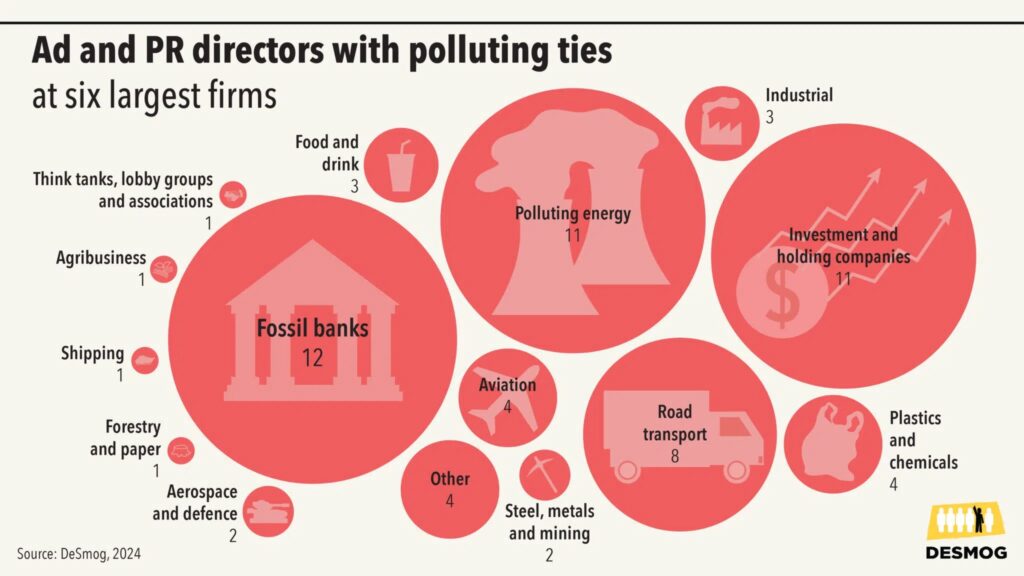

At the world’s six largest advertising and PR companies – Omnicom Group, WPP, Interpublic Group (IPG), Publicis Groupe, Dentsu and Havas – 32 out of 64 executives have been found to have significant experience in carbon-heavy sectors like fossil fuels, plastics, utilities and aviation, with 22 still serving such roles in these sectors.

That’s according to an investigation by DeSmog and Clean Creatives, which has found that these six firms – with $67B in revenue in 2022 and hundreds of subsidiaries worldwide – have held at least 163 contracts with fossil fuel clients over the last two years. It highlights the conflicts of interest presented by some of the leading communications executives in the world, as governments, campaigners and their own employees urge them to stop producing greenwashing campaigns that benefit fossil fuel companies.

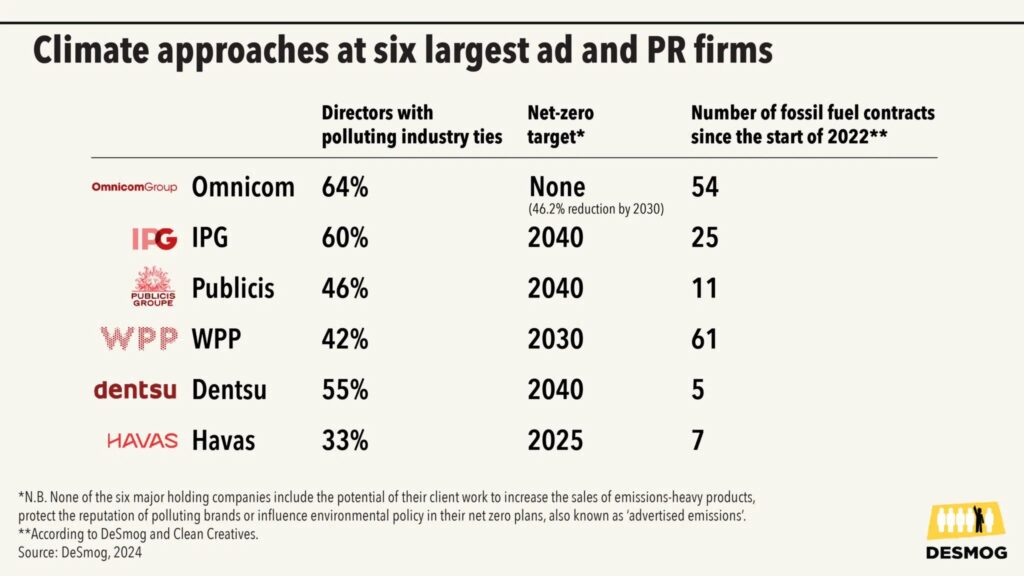

Omcom has the most “climate-conflicted board”, with seven of its 11 directors directly affiliated with polluting sectors – this includes roles at Chevron’s soon-to-be-subsidiary Hess Corporation, fossil fuel fund manager Global Infrastructure Partners, and previous positions at some of the largest private fossil fuel financiers. Omcom itself has held 54 fossil fuel contracts since the beginning of 2022.

“The tangled web of board memberships is a key barrier to agencies moving away from working with fossil fuel clients,” said Belinda Noble, founder of industry climate campaign group Comms Declare.

The links between communication firms and polluting industries

All six companies in the investigation have publicly pledged to slash carbon emissions, which DeSmog says creates “an appearance of climate awareness” and helps them recruit younger talent looking to join companies with good eco credentials and avoid those with fossil fuel clients. However, these firms don’t seem to be ending any of their oil- and gas-related contracts, and concerned employees raising issues about the same have met with pushback from the highest executives.

Omcom has three contracts with Exxon, the world’s third-most profitable oil and gas company, and the highest-polluting investor-owned fossil fuel company since the 2015 Paris Agreement. Exxon has published YouTube videos promoting carbon capture and storage as emissions reduction methods – but these technologies are usually used to extract more oil and scientists have questioned their ability to truly affect climate change. Another campaign saw ExxonMobil (its automotive fuel brand) position petrol cars as a way of “disconnecting”, taking a shot at electric vehicles.

“When you’re in a position like I am, trying to make change at an agency to make it more climate-minded, and you see this research, it makes you wonder whether it’s all a bit of a waste of time,” one Omnicom employee involved in staff-led climate groups said.

IPG came second on the list of pollution-linked executives, with six of its 10 board members having experience in natural gas, shipping and plastics. This is the only firm in the list that has established a policy for taking on fossil fuel projects, one requirement being that clients must set emission-cutting goals aligned with net zero for 2050 – but employees suggest the policy is weaker than it appears, with one source saying: “You could drive an oil tanker through some of the loopholes in it.”

McCann, one of IPG’s marketing agencies, will this year pitch to renew its contract with Saudi Aramco, which is the largest oil company globally and the heaviest state-owned fossil fuel polluter in history, accounting for 3.6% of the world’s carbon emissions since 1854.

WPP board chair Roberto Quarta, meanwhile, has seven current and past links to polluting industries, the highest in the analysis, while another member was an executive at Goldman Sachs, one of the top private fossil fuel funders – a total of 12 directors have such ties. Meanwhile, five out of Dentsu’s nine directors have such just under half of Publicis’s 13 directors have similar links.

At Havas, three out of nine executives have ties with carbon-heavy sectors, including chairman-CEO Yannick Bolloré and his sister Marie Bolloré, who are connected with the oil logistics division of Havas’s parent company, the family-run Bolloré Group. The firm last year won a contract to manage the global advertising spots for Shell, the fourth-largest oil company.

Despite requests for comment from DeSmog to the firms and their directors, all but one responded. And the one that did – WPP – declined to comment.

Younger board members symbolise hope

Even though five of the six holding companies have net-zero goals, these plans only count emissions generated by their own operations, like employee travel or building energy use. All six are members of industry initiative Ad Net Zero, which entails a pledge to slash such in-house emissions. But its action plan does not entail the wider climate impacts of its work, such as campaigns that enhance the reputation of polluting clients and could divert pressure to reduce emissions.

Advertised emissions, which refers to pollution linked with ad-generated sales growth of carbon-heavy products and services, have been recognised by the UN-led Race to Zero campaign, which works to help businesses, universities, cities, etc. to eliminate their carbon emissions by 2050 – Dentsu’s advertised emissions in 2022 were 32 times the size of its own operational carbon footprint.

“Board directors have been adamant publicly about their dedication to climate action and their companies’ pivot towards net zero,” said Sarah Chow, an investment analyst at ethical pension fund Future Super, which has been attempting to engage with Publicis and WPP on pollution-linked work. “But behind closed doors and after public [annual general meetings], our relations with these directors have gone cold.”

Experts also note that these firms’ potential for change is slowed by their parent company structure, which limits subsidiaries’ power to make independent decisions on subjects like climate change. “You have to remember, these few leading directors are setting the tone and agenda not just for the overarching company, but multiple chains of companies,” said Nadeem Khan, Board Practice and Directorship programme lead at the University of Reading.

In certain parts of the world, legislators are introducing regulations and initiatives to clamp down on greenwashing, including the EU, California and the UK. In the latter, the Advertising Standards Authority banned ads by Shell and Repsol (created by WPP and Omnicom agencies) for making misleading claims about renewable energy investments in June, followed by two more bans on Toyota ads promoting planet-harming driving (made by a WPP subsidiary).

These bans can pose a legal risk to board members at ad and PR companies, since they can potentially lead to reputation damage and subsequent financial losses. Some of these firms are recognising this, with WPP and Dentsu both mentioning such risks in public documents.

Many are calling for – and banking on – a changing of the guards, with more climate action expected as younger generations take up executive positions. “Board directors are often removed from the actual problems their employees face,” said Chow. “They need fresh blood that understands the pulse of a company’s workforce, and what the workforce wants.

One WPP employee they feel “very ashamed” to be part of the comms industry. “There are people in it who do genuinely want to use their skills and knowledge for positive change – lots actually – but unfortunately none of us hold positions of power and there’s only so much we can do.” Maybe it’s time for the communications industry to pass the baton.