10 Mins Read

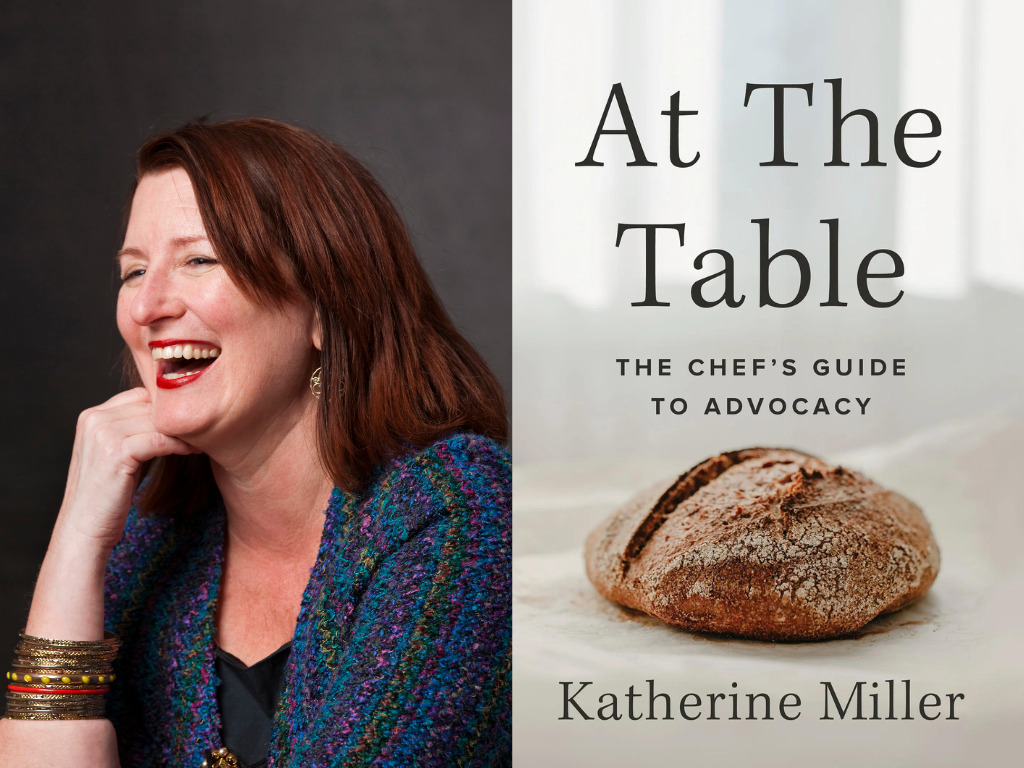

Thin Lei Win talks to former James Beard exec, GWU Terker fellow and communications expert Katherine Miller about her new book and why chefs are the perfect advocates to bring about structural change to food systems.

I used to think I must be abnormal, given how obsessed I am with food.

While having breakfast, I’d be thinking about lunch and planning for dinner. My holiday destinations and schedules revolve around where and what I want to eat. I travel hours to taste something special.

In fact, multiple ex-boyfriends have commented incredulously on the amount of time I spend thinking about, listening to, watching and reading anything food-related. After a quick research for this issue, however, I’m glad to report that I’m pretty normal.

Did you know that:

- 43% of Instagram users have food and drinks as their main interest? Only two other passions rank higher than food – travel (45%) and music (44%). Since Instagram crossed the 2-billion-user mark last year, this makes food and drinks the key draw for at least 860 million users.

- Videos on TikTok with the #foodtok hashtag have been viewed more than 64 billion times?

- “(Food videos) remain the most watched content type across all platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, and YouTube”?

Obviously, I feel vindicated, but more importantly, these statistics also show how intertwined food and entertainment are these days and the power of chefs to become our inspirations and guides.

Katherine Miller is banking on chefs to use this power for the greater good. She’s urging them to become advocates in making our food systems fairer, healthier, and more sustainable.

“Chefs can help translate what goes into producing our food to what is on our dinner table – and can help us all understand how food policy, from cottage food laws to global fishery management treaties, affects what is available to us and at what cost,” she writes in At The Table: A Chef’s Guide to Advocacy which was launched in Washington D.C. last week.

“Chefs are a key ingredient in making not just restaurants, but the food system itself, more just and sustainable.”

From Skeptic to Spearheading

In 2012, Miller, who had spent more than a decade working for the Democratic Party before helping non-profits, corporations, and policymakers with strategic communications, was approached in 2012 to design and lead a training focused on turning chefs into political advocates.

She was skeptical at first, but realised food is the common thread that runs through pretty much all the other work she has been doing – climate change, gender equity, sexual violence, global health, et al – and jumped in with both feet.

She helped set up the James Beard Foundation’s (JBF) Chef Bootcamp for Policy and Change, and became the founding executive director of Chef Action Network, and vice president of impact at JBF, whose awards are some of the most coveted in the food industry.

Grist put her in its 2017 “Fixer” list – a selection of 50 people leading us into a sustainable future – and the same year, Food & Wine called her one of the most innovative women in food & drink.

At The Table is a slim book that is supposed to act as a guide for chefs who want to lead hunger relief efforts, support local farmers, fight food waste, or confront racism and sexism in the industry. It is, understandably, U.S.-centric but much of it is applicable for people who want to advocate for better food systems in general.

The conversation below has been edited for length and clarity.

Thin Lei Win: What prompted you to write the book?

Katherine Miller: I’d always wanted to figure out a way to put the stories together. I think the (James Beard’s) Bootcamp is such a boutique and unique experience. But I no longer work there and it is an invitation-only training for influencers themselves.

There are many more chefs and restauranteurs that could benefit from this type of thinking. So this is really the off-the-shelf way of reaching a much larger audience.

The other thing I was excited about was that culinary schools don’t teach anything other than culinary aspects. Some are getting better but that’s at the graduate level. There’s no curriculum that introduces chefs how to be a business owner or how to be an ethical or community-participatory business owner.

In the US context, there aren’t many people who didn’t start as a waiter, a waitress, a bartender or a dishwasher. So if the chefs are informed and inspired and activated to participate more broadly, for both better business practices and democracy, won’t their staff be too?

TLW: Obviously, a lot of the examples you cite are U.S.-based. But I feel it’s also applicable to chefs and foodies outside the U.S. too.

KM: Absolutely. It’s a very brief anecdote, but The Chefs’ Manifesto is an organisation that was set up outside the U.S. (Me: by Paul right?) Yeah. When I was at James Beard, we certainly worked together on that. And towards the end (of the book) is an Australian chef who has sort of taken the same practices around advocacy to work on food waste reduction.

I’ve worked all over the world for different foundations and organisations and a lot of the training methodology that really honed with chefs was used to train land advocates in Nigeria and medical advocates in China. So, it has a lot of applicability, but as you know, your editors will always say, “Pick an audience!”.

My hope is that people will take some of the tips and tools that are there and do two things. One is they’ll see the food system as a system and think about all the choices that we make, whether it’s on the plate or within our community.

The second is that the tips and tools are pretty universal and if someone is interested in advocacy at any one of those levels, maybe a chef story makes it more palatable.

TLW: It was fascinating to read your book and your experience on how you came to advocate for this issue.

KM: I mean, you probably know from your work that this food system is like a deeply rooted, overgrown bush, right? It’s hard to sort of rip it all out, because you can’t just start over again, so you’re constantly rebuilding the system. What I love about chefs and restaurants in particular is they’re sort of at the nexus of that system.

They work with the farmers and the producers, they’re subject to all sorts of price fixing and policy pieces, and they also are the ones who translate (these issues) for customers. They have been huge economic drivers in their communities, but they’re also like – and this is part of the challenge especially on wage, workforce, and benefits – perpetuators of an antiquated system.

For me, the book is really about how that system can look in on itself, and then step out and try and make a little bit of a difference.

TLW: Compared to when you first started Chef Bootcamp for Policy and Change in 2012, how far have we come? Or have we not come far enough yet?

KM: We certainly haven’t come far enough. I mean, we are staring down the literal barrel of federal shutdown once again. The Farm Bill again is sort of hostage to that. Also, the USDA calls fruits and vegetables specialty crops and (they) still get minority funding within the Farm Bill.

We’re still staring at hundreds of millions of dollars that will be spent to maintain the status quo in terms of subsidies and the dominance of a global food system that is optimised for price and convenience and shelf life.

So we haven’t come far enough. But what I do think is amazing is that every day more and more people are willing to step into an arena that feels alien, or combative, or opaque, and try and make sense out of it because of their desire to see something different.

When I think about Michel Nishan, who helped found Wholesome Wave and works at this intersection of food as medicine and produce prescriptions, that took a decade.

Policy work is hard work but you need fresh new voices to do it. You need people who are willing to take the long game. But you also need people who will bring some creativity to the table. That’s why I like chefs.

So I think we have a long way to go and but I am always optimistic about the number of people who step into that arena. I don’t know if it’s still the case but when I left JBF there were over 1,000 names on that waiting list to get in to the programme.

TLW: You wrote about how there’s just so much food content as lifestyle and entertainment offerings. Yet that seems to be two very different camps between people who watch them and people who look at food from a systems perspective. How do we get more chefs as well as ordinary consumers to become more interested in things beyond what’s for dinner and how cheap or tasty it is?

KM: We all have to eat every day, right? Food is the thing that if you eat too much, it can kill you and if you don’t have enough, it can kill you. Yet at the same time, consumers are really driven by that intersection of price, convenience, and flavour memory. Like what feels good to me at this moment that I have time for and can afford? So that’s always going to be a challenge.

What I love about chefs in particular, again, is this translation aspect. Also, the food system is really complicated. Who really wants to have a conversation that 10 global companies control so much of our foods?

When people go to the grocery store, they have this romanticised vision of what they’re getting and it’s not always the case. So chefs can really help translate the raw ingredients.

The other thing is they can help take the judgment out of it. Dining is a universal experience. Eating is a universal experience. But too often food systems advocates resort to the language of a value judgement, like, “We have to teach people to cook because they don’t know how to cook” or “They’re making bad choices”.

No! We have a system where processed, cheap, convenient food is ubiquitous. You actually have to go out of your way to make different choices and a restaurant can help educate you about that. I feel like chefs and restaurants can translate what’s happening on the plate in a way that isn’t passing judgment on your choices.

Because I just can’t anymore with, like, the food systems advocates who are righteous in the way that they message about how consumers should spend their money. No one wants to hear that.

TLW: Yeah, it becomes yet another layer of guilt that you have to live with because you are doing it wrong.

KM: I did a project a few years back before I started working with chefs. It was around feelings about government programmes and we interviewed about 100 recipients.

One of the things that has always stuck with me was a woman who talked about how every time she went to go see her counsellor, they went through her grocery expenditures and asked her why she bought something. In one case, it happened to be a cake. Her counsellor was like, “Why did you buy a cake?” And she was like, “It was my child’s birthday!”

Sometimes you just want a cake and the cake you can afford is not from the boutique cake maker, and the fact that we make people feel bad about those decisions, as opposed to showing them how you can make other choices, or showing what the impacts of those other choices are in a way that’s positive and affirming and isn’t judgmental.

TLW: Speaking of which, everything has become extremely polarised, as you know. Consumption of meat is an example. In this atmosphere, do you think bipartisan action is still possible? As somebody from the outside of the U.S. looking in, it just feels like the gap is getting wider.

KM: I think this is an interesting thing. I’ve spent a lot of time working in establishment electoral politics, and every election cycle I say, “I’ve never seen anything quite like this!”

At this moment, what I see within the power of food and the power of chefs is that they are on every street corner. We have them in every community around the world and (they have) the ability to support that community and are willing to listen at the community level.

Meat is a great example. Our food system globally, but certainly in the U.S., is subsidised to a point that makes meat consumption possible and affordable for a large number of people. You can see it in the amount we eat. It’s not always the best meat, like it’s not the most humanely raised or free of antibiotics. But it’s cheap and convenient and easy.

People say all the time, “We should stop that.” You cannot rip out the roots of a global meat enterprise without something to replace it with. And you can’t replace it overnight. So what we’re talking about is gradual systems change at all the levels.

We’ve got to crack down on really unethical lobbying. We have to change the incentives. We have to have meaningful enforcement. We also have to have a consumer that is ready to make that decision. I just think chefs can do that.

From a partisan perspective, I think we’re probably at the worst time that we’ve ever been globally and in the U.S. But I think community-based leaders are gonna help us get through it.

When I look at the anecdote in the book around the Bay Area Ranchers Co-Operative, that’s a community-led effort to get the thing that they need that will help create a new economy, and do all the things that you want from better, higher quality meat that’s raised more ethically. That didn’t come from Washington.

TLW: Anything else you’d like to add?

KM: At our heart, we’re all eaters. It’s our unconscious political act that we do every single day. And my hope is that with the book, there’s a very simple framework that anybody can use and that chefs will help guide us a little in how to get involved and do it in ways that open conversations.

This is an edited and web-adapted version of the 29th September 2023 edition of the Thin Ink newsletter, a weekly publication on food, climate and where they meet by journalist Thin Lei Win – subscribe here.