6 Mins Read

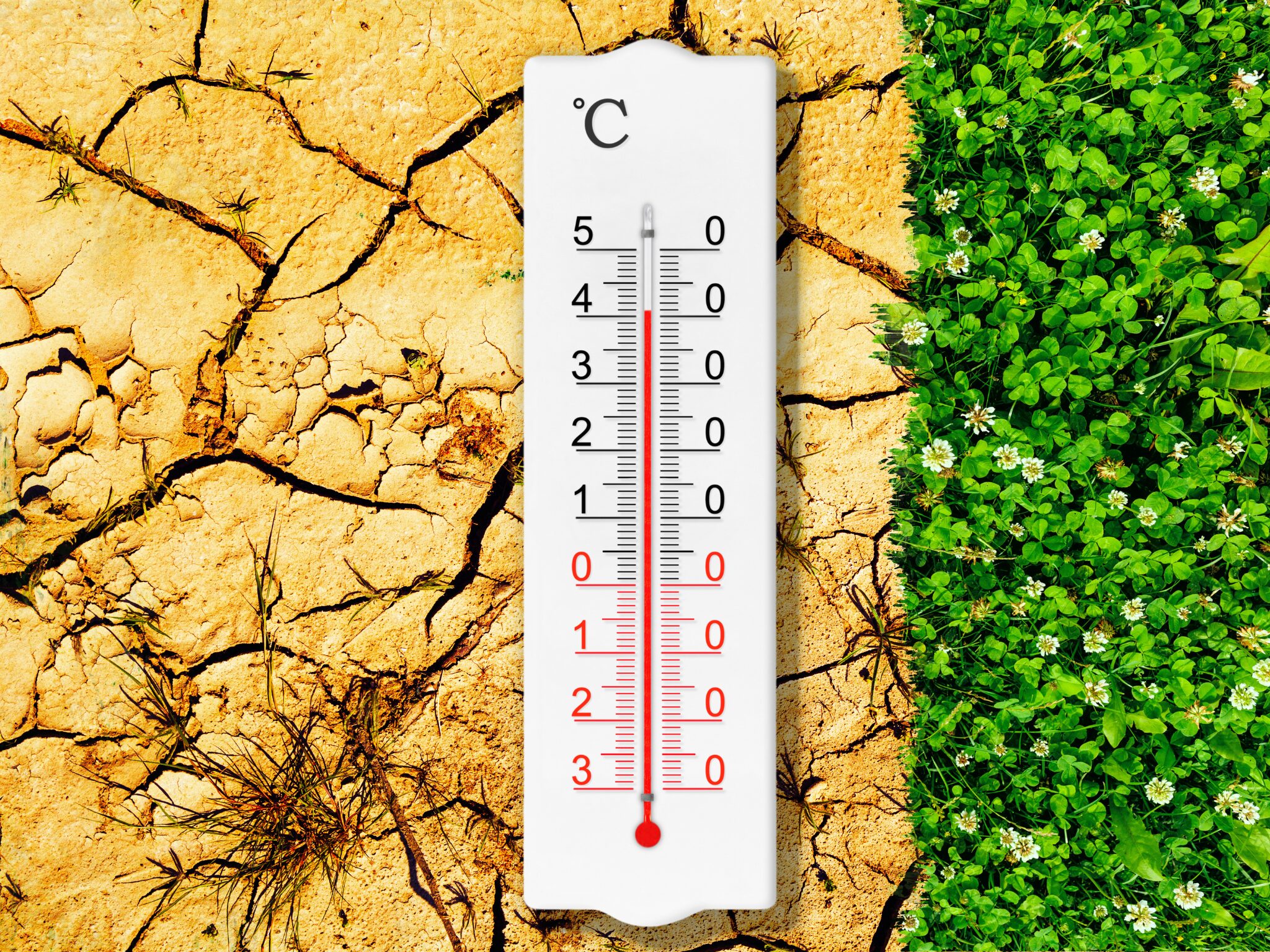

A majority of the world’s top climate scientists say we’re on our way to breaching the 2.5°C barrier this century – and only 6% believe we’ll meet our 1.5°C budget. The only way we stand a chance is through heavily accelerated action.

In 2015, global leaders struck a landmark deal to adopt the goal to limit temperature rises to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels by 2100. Almost a decade later, we’re further away from that objective, with 94% of climate experts saying the world will miss this target, opening itself up to catastrophe for humans and the planet.

That’s according to a new survey of 380 scientists – all part of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – by the Guardian. To say the results make for grim reading would be a major understatement: 77% of the respondents think we’ll blast past post-industrial temperature hikes of 2.5°C, with 42% feeling we’ll go over 3°C.

In fact, there are more scientists who think the world will cross the 4°C barrier than those who say we’ll meet the 1.5°C goal this century. The latter was chosen as a target to prevent the worst effects of climate change – the devastating effects of the crisis already being seen around the world have come during a time when global heating has only risen by 1.2°C on average (in the last four years).

Current projections show we’re on track to reach 2.7°C, and that the climate crisis could cause a billion deaths by the end of the century. “The world’s response to date is reprehensible – we live in an age of fools,” said one South African scientist. “I expect a semi-dystopian future with substantial pain and suffering for the people of the Global South.”

The survey has garnered strong reactions from climate experts and global leaders, who have labelled it a “wake-up call” for global climate efforts. “The goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C is hanging by a thread,” said the official spokesperson, UN secretary-general António Guterres.

Capitalism, disinformation and a lack of will

Guteress’ spokesperson noted that “the battle to keep 1.5°C alive will be won or lost in the 2020s – under the watch of political and industry leaders”. Their lack of effort was pinpointed as the single biggest reason behind the world’s current failure to tackle climate change.

Nearly three-quarters of the IPCC scientists polled blamed it on a lack of political will, while 60% ascribed it to vested corporate interests, like the fossil fuel industry. The most glaring example of that was perhaps at COP28, the UN’s climate summit in Dubai last year, headed by the chief of the UAE’s national oil company, who claimed there was no science showing that a fossil fuel phaseout would benefit the climate.

“I think 3°C is being hopeful and conservative. 1.5°C is already bad, but I don’t think there is any way we are going to stick to that,” said climate scientist Ruth Cerezo-Mota, who has developed depression over the future of climate change. “There is not any clear sign from any government that we are actually going to stay under 1.5°C.”

According to the latest IPCC assessment, 3°C of global heating would drown cities like Shanghai, Rio de Janeiro, Miami and The Hague, as they’ll reach below sea level. “It is the biggest threat humanity has faced, with the potential to wreck our social fabric and way of life. It has the potential to kill millions, if not billions, through starvation, war over resources, displacement,” said James Renwick from Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. “None of us will be unaffected by the devastation.”

“If the world, unbelievably wealthy as it is, stands by and does little to address the plight of the poor, we will all lose eventually,” added Dipak Dasgupta from the Energy and Resources Institute, New Delhi.

Only 27% of scientists think a lack of capital is a concern for the climate fight – most believe the money exists for a green transition. “Multiple trillions of dollars were liquidated for use during the pandemic, yet it seems there is not enough political will to commit several billion dollars to adaptation funding,” said Trinidad and Tobago scientist Shobha Maharaj.

Additionally, only 6% and 4% pointed to a lack of green technology or scientific understanding, respectively, as an issue. But disinformation is a major concern for respondents, who said it was polarising society, exacerbating poor public comprehension of the risks, and making people think we have almost all the climate solutions we need.

Another barrier was the overconsumption in rich nations. “I feel resigned to disaster as we cannot separate our love of bigger, better, faster, more, from what will help the greatest number of people survive and thrive,” said one scientist from the US. “Capitalism has trained us well.”

Climate scientists urge optimism, action and faith in the youth

Younger scientists were more pessimistic in their assessment of the future, with 52% of respondents under 50 anticipating temperature rises over 3°C, versus 38% of over-50s. Female scientists were also in the same boat, with 49% expecting this hike, versus 38% of male respondents.

Many scientists have lost hope for the future – or are close to doing so. Camille Parmesan, from the CNRS ecology centre in France, was one of them, having almost given up 15 years ago. “I had devoted my research life to [climate science] and it had not made a damn bit of difference,” she said. “I started feeling [like]: ‘Well, I love singing, maybe I’ll become a nightclub singer.’”

But things changed when she saw the dedication of youth activists at the 2009 UN climate summit in Copenhagen. “All these young people were so charged up, so impassioned. So I said I’ll keep doing this, not for the politicians, but for you,” she recalled.

Cerezo-Mota echoed this sentiment: “I really don’t know what needs to happen for the people that have all the power and all the money to make the change. But then I see the younger generations fighting and I get a bit of hope again.”

But the lack of action has left climate scientists at the end of their tether. Parmesan noted how the big difference between the last and latest IPCC report was that “all of the scientists I worked with were incredibly frustrated”. “Everyone was at the end of their rope, asking: what the fuck do we have to do to get through to people how bad this really is?” she said.

“We did our science, we put this really good report together and – wow – it really didn’t make a difference on the policy,” said Lisa Schipper from the University of Bonn. “It’s very difficult to see that, every time.”

In response, Christiana Figueres, the UN climate chief who oversaw the landmark 2015 Paris Agreement, said: “These climate scientists are doing their job. They are telling us where we are, but now it’s up to the rest of us to decide what this moment requires of us and [to] turn the seemingly impossible into the new normal.”

But scientists are also encouraging people to not give up hope. “Climate change will not suddenly become dangerous at 1.5°C – it already is,” said Peter Cox from the UK’s University of Exeter, UK. “And it will not be ‘game over’ if we pass 2°C, which we might well do.”

Less than a quarter of respondents believe think temperature rises will be restricted to 2°C. One of them, Maisa Rojas – who is Chile’s environment minister – said: “We need to communicate that acting on climate change can be a benefit, with proper support from the state, instead of a personal burden.”