The Arctic’s On Fire, the Amazon’s Destroyed, and 1.5°C Is Out the Window – But Are We Reaching Peak Emissions?

5 Mins Read

Recent extreme weather events serve as a warning of what’s to come if governments don’t get their house in order, with most climate scientists now prophesising “catastrophic” 2°C warming.

Hurricane Helene has ravaged six states, some far from the coast, and killed over 220 Americans. The images are harrowing and terrifying, and the worst part is that such disasters could become increasingly common, thanks to climate change.

All this while vice-presidential candidate JD Vance continued to question the validity of the climate crisis during his debate with Democratic counterpart Tim Walz. Vance may have called it “weird science”, but the very real impacts of climate change are being felt across his nation, and the world.

Climate scientists have repeatedly warned that the goals of the Paris Agreement – which Donald Trump pulled the US out of – are in jeopardy. The target of keeping temperature rises down to 1.5°C by 2100 from preindustrial levels seems out of reach now. We’re currently on course to see increases from 1.7°C to 2°C by 2050, and this would bring about catastrophes unlike what we’ve faced so far.

A new survey of 211 climate scientists – all authors on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) – echoes this sentiment, with 86% of experts believing global heating will surpass 2°C by the end of the century if things remain unchanged.

For context, at 2°C, an extreme heat event that happens once a decade would take place 5.6 times (versus 4.1 times for 1.5°C) every 10 years. This kind of heating would raise sea levels by up to 10 metres and trigger the collapse of ice sheets, and destroy 99% of coral reefs (compared to 70% for 1.5°C). And a larger share of animals and insects would lose their habitats.

Experts agree on 2.7°C warming forecast

The Arctic, home to the world’s carbon-rich peat, is heating up faster than any other region on the planet, owing to a constant stream of intense wildfires. When it burns, the fire slowly goes underneath the surface, becoming harder and harder to extinguish.

The carbon released from burning peat has sent the Arctic Circle’s emissions – already at their third-highest on record – through the roof. And according to climate scientists, a third of the Earth’s permafrost will be eliminated by 2050 in a high-emission scenario.

Meanwhile, a recent report revealed that the Amazon has lost 12.5% of its forest cover between 1985 and 2023 to deforestation, mainly for mining and agriculture. That equates to 88 million hectares across South America, an area the size of Germany and France combined.

Here’s why that’s worrying: the Amazon rainforest is home to half of the world’s tropical forests and over three million species of plants and animals, but continued deforestation (both legal and illegal) has put 10-47% of its forests – and much of its biodiversity – at risk of collapse by 2050.

These are just a couple of examples of the long-term damage climate change is leaving across the world, from the tropics to the poles. And if our climate policies don’t change in a major way soon, things will only get much, much worse.

The aforementioned survey, published in the Communications Earth & Environment journal, found that while most climate scientists believe we’re on course for a 2°C reality, 58% think there’s a 50% chance that we’ll actually cross 3°C by or before the end of the century.

According to the IPCC’s latest assessment, 3°C of global heating would drown cities like Shanghai, Rio de Janeiro, Miami and The Hague, as they’ll reach below sea level. The survey’s median estimate was a 2.7°C rise in global temperatures, which it suggests will have catastrophic consequences for the planet.

Can we reach peak emissions this year?

The results chime with a similar Guardian survey of 380 IPCC scientists earlier this year, in which 77% of respondents said we’ll cross the 2.5°C barrier, while 42% said global temperatures will rise by over 3°C. Meanwhile, only 6% thought we’d be able to meet the 1.5°C goal, which was even lower than those who felt we’d go over 4°C.

But both these polls had something in common: hope. In the Communications Earth & Environment study, two-thirds of the climate scientists say the world will reach net zero by 2085, in line with a 2°C scenario. They are also optimistic about the potential of carbon removal, believing that this stech could eliminate up to five gigatonnes of CO2 per year by 2050, which is on the lower end of the Paris Agreement’s goals.

Summing up this message of hope, University of Exeter’s Peter Cox, one of the respondents of the Guardian survey, said: “Climate change will not suddenly become dangerous at 1.5°C – it already is. And it will not be ‘game over’ if we pass 2°C, which we might well do.”

“Climate scientists certainly have expertise in climate systems and energy transitions, but it will be policy implementation and societal change that actually determine how quickly emissions drop,” said Damon Matthews, co-author of the Communications Earth & Environment research and a fellow IPCC scientist.

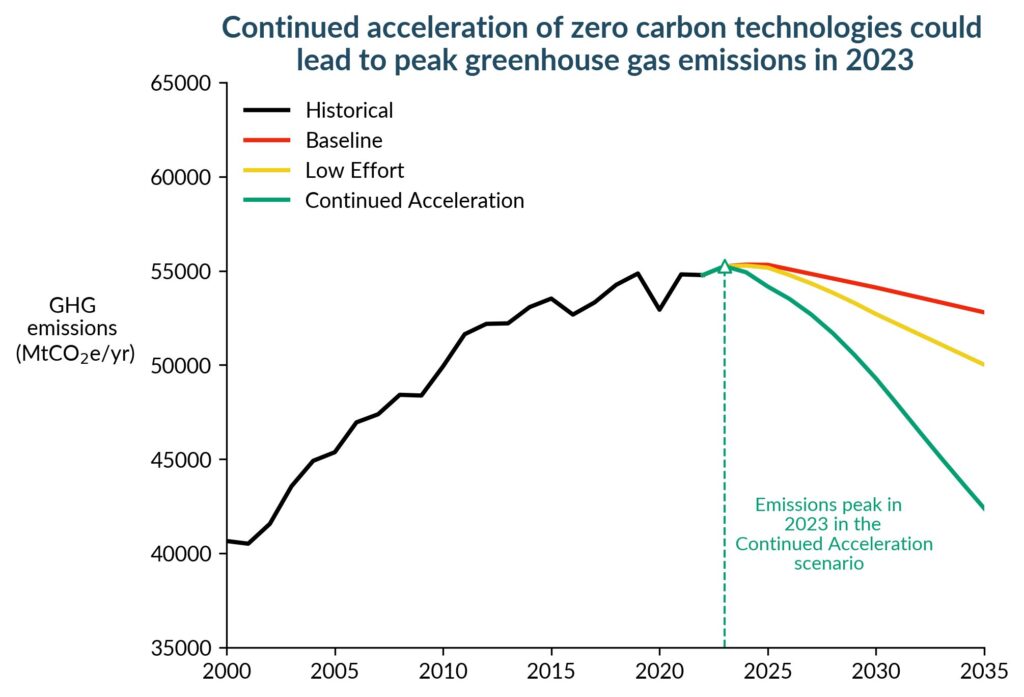

Maybe there is a little bit of hope. Two major climate research organisations – Bloomberg NEF and Climate Analytics – have said that it’s possible 2024 could be the year we reach peak emissions, a year ahead of what many reports have suggested in the past.

Experts have said that fossil fuel emissions could peak by 2025 after Russia’s war on Ukraine spurred a spike in clean energy investments globally. This is also the year that emissions must peak if we’re to realise the goals of the Paris Agreement.

“Our analysis from last year found that if wind and solar continue to accelerate at the pace that they have been, consistent with historical trends, then there’s a 70% chance that emissions would fall in 2024,” Climate Analytics’s Neil Grant told ABC News.

Whether we truly will reach peak emissions this year, we’ll find out in a few months. “Ultimately, the decision as to what we do and how we respond to the climate challenge is up to policymakers and the public that they represent, and I think the full range of outcomes is still very much on the table,” said Matthews.