More Heat, More Inflation: Study Confirms That Climate Change is Driving Up Food Prices

5 Mins Read

Climate change and related extreme weather events will speed up global inflation and lead to higher prices for food, goods and services in the coming years, according to a new study.

The food industry’s emissions are heating up the world, and these higher temperatures are making our food more expensive. That’s the alarm bell being sounded by researchers at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research and the European Central Bank in Germany, who have linked climate shocks to increasing inflation and food costs.

Published in the peer-reviewed journal Communications, Earth and the Environment, the study involved an analysis of over 27,000 data points derived from consumer price indexes and weather data from 121 countries over the last 30 years. This information was used to measure how changing temperatures affect inflation and combined with climate change projections in a range of emissions scenarios.

The research found that in the worst-case scenario – where not much else is done to reduce the planet’s greenhouse gas emissions – the climate crisis could drive up the cost of food by as much as 3.2 percentage points annually, while average inflation could rise by up to 1.2 percentage points. They might look like small numbers, but they will worry banks that fight inflation, such as the US Federal Reserve, according to study lead Max Kotz.

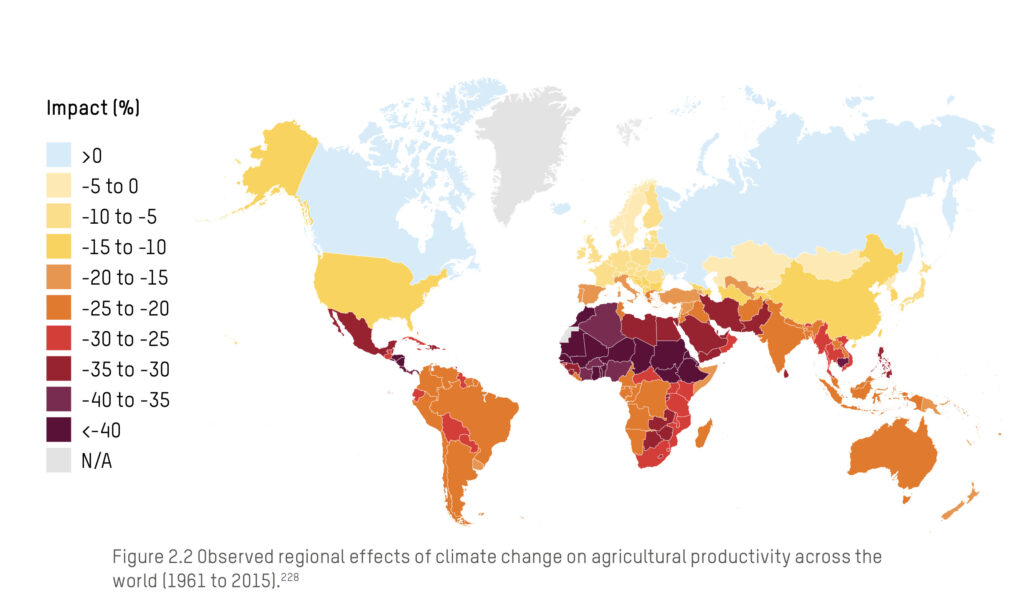

“There are these productivity shocks that we know about from climate change, from the weather phenomena caused by climate change, from heat waves and so forth to reduce agricultural productivity,” said Kotz, a climate scientist at the Potsdam Institute. “Those also then have a knock-on effect on food inflation, on headline inflation.”

Even best-case scenarios will see higher food prices

Food prices reached a record high in 2022, while climate-change-induced crop failures and poor harvests have also led to increased food shortages, whether it’s tomatoes or stonefruits in Italy and Spain, wine in Australia, Argentina and South Africa, potatoes in Peru and England, or even maize in India and Zambia.

This has inevitably caused price hikes for food, affecting healthy access to nutritious food across the world. In 2023, 21.6 million more people faced a high level of acute food insecurity than in 2022 – a 10% increase. It demonstrates the need to transition towards a low-impact food system (which currently accounts for about 40% of global emissions), where much less land and water are required to grow significantly more crops.

But the study demonstrates how far the damage from climate change has come, and how long-lasting its impact will be. Even in a best-case scenario, overall inflation could hike by up to 0.3 percentage points each year, and food inflation by 0.9 percentage points, until 2035.

Kotz told ABC News that “shocks” to agricultural productivity would be the main channel underlying the impact of climate change on food inflation, which is tied to extreme weather events that could upset the global economy. And while the impact on food prices from every 1°C increase in average monthly temperatures will last for up to a year, it’s not just excess heat that will have an impact.

Excess wet conditions could trigger a hike in food inflation too, while excess dry conditions will have implications during hot months or in warmer regions, though these will likely be less significant and more short-term.

“The physical impacts of climate change are going to have a persistent effect on inflation,” said Kotz. “This is really from my perspective another example of one of the ways in which climate change can undermine human welfare, economic welfare.”

The Global South will be hit harder

The researchers noted that rising food prices and inflation will affect people in both richer and poorer countries. In Europe, which witnessed over 70,000 excess deaths due to extreme heat in the summer of 2022 – and is said to be unprepared for future climate risks – the higher temperatures were responsible for an increase of 0.34 percentage points in overall inflation and 0.67 points in food prices. In areas like Romania, Hungary and parts of southern Europe, these hikes were even greater.

However, the scale of impact is disproportionate, with more vulnerable countries in the Global South (especially those in Africa and South America) the hardest hit. As some of the hottest weather occurs in these nations, the impact of climate change on food supplies and prices will be much larger here. “They’re closer to higher temperatures at which further temperature increases start to be damaging, especially for most crops,” Kotz told ABC News.

In high-latitude regions, only seasonal changes drive up inflation – increasing temperatures cause upward inflationary pressures (where prices are hiked due to short supply) during the hottest months of the year, and downward pressures in the colder months. In the lower latitudes, however, higher average monthly temperatures result in upward inflation all year round.

This is consistent with other studies that have shown the imbalance of climate impacts on people in lower-income and more vulnerable countries. Research has indicated that the Global North is responsible for 92% of our excess emissions, but 91% of all extreme-weather-related deaths occur in developing countries mostly in the Global South.

“Because of human-[caused] emissions, certain types of weather extremes are going to be intensifying,” said Kotz. “More and more temperatures are generally going to be increasing, and we know that there are negative implications of those kinds of changes on things like agricultural productivity.”

The study notes that without significant mitigation of GHG emissions, inflationary pressures will remain “persistent and sizeable”, adding that future adaptation to climate change “through unprecedented technological changes” could help limit food price hikes. These include space cooling projects, which can limit heat stress impacts on labour productivity, and crop switching, which could circumvent agricultural productivity losses.