How Food Companies Should Report & Reduce Their Emissions with Better Progress Markers for Investors

5 Mins Read

Are corporate climate actions on par with their emissions targets and disclosures? A new report explores this very question.

Food companies are making some progress on reducing their greenhouse gas footprints, but they’re slow to address scope 3 emissions, according to a new analysis of corporate carbon disclosures.

Sustainability non-profit Ceres looked at the emissions reporting of the 50 of the biggest agrifood companies in North America – part of its Food Emissions 50 initiative – to provide investors clarity around the disclosures and set out best practices for further progress.

These include the likes of processing giants such as ADM and Ingredion, restaurant chains like McDonald’s Yum! Brands and Chipotle, meatpackers such as JBS, Maple Leaf and Tyson, CPG behemoths including Kraft Heinz and Mondelez, as well as retailers like Kroger and Walmart, among others.

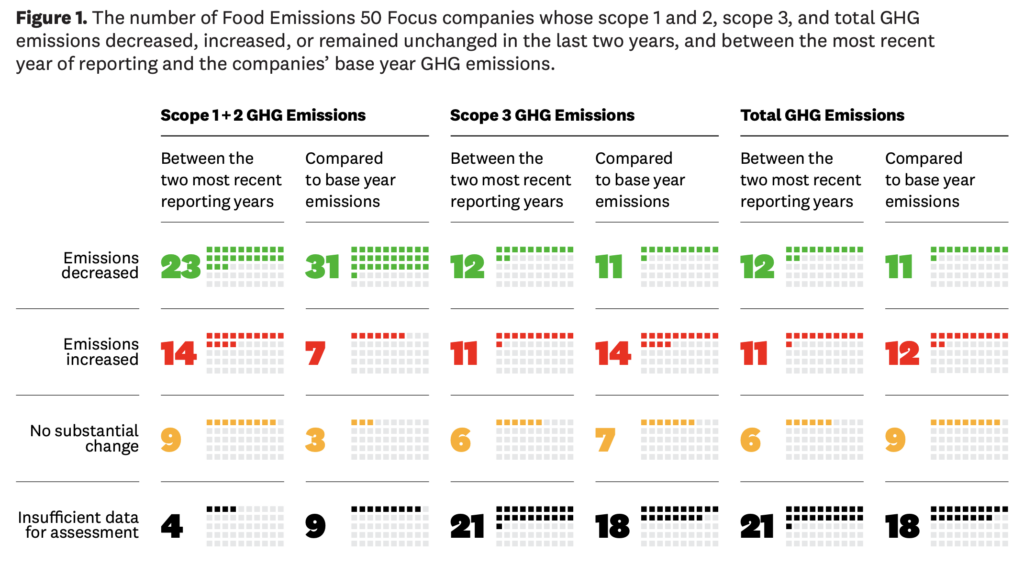

It found that 31 of the companies (62%) have reduced scope 1 and 2 emissions compared to their base year, but only 11 (22%) did so for their scope 3 emissions (which include the full supply chain).

On the flip side, the scope 1 and 2 emissions of seven firms have actually risen, and this doubles when you look at scope 3 emissions. The lack of focus on the latter is a problem, since these activities account for up to to 95% of corporate emissions. Without addressing them, aligning with the 1.5°C wouldn’t be possible.

The report calls on food corporations to act on scope 3 emissions. Outlining just how outsized their impact is, it notes how one company’s total emissions increased by 23% because – even after it cut scope 1 and 2 emissions by 77% – its scope 3 emissions were up by 27%.

The connection between emission disclosures and reductions

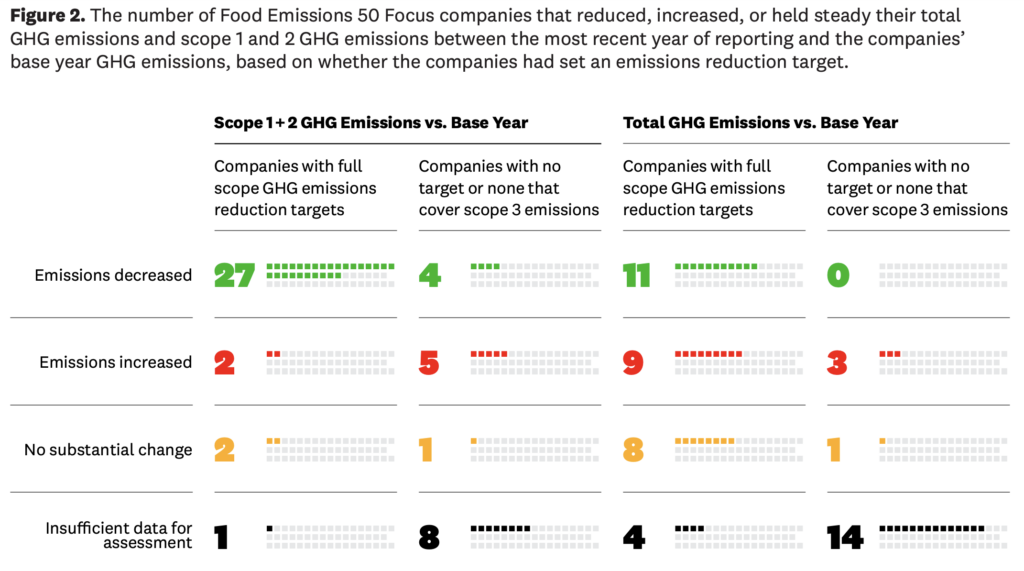

Ceres revealed that companies with robust emission reduction targets that include scope 3 and are validated by the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) are more likely to have reduced their emissions.

Of the companies that had full-scope targets lowered their emissions, 11 managed to lower their emissions. In contrast, no firm without such goals reduced their overall emissions.

“it is likely that were they to disclose these emissions, these companies would show that their scope 3 GHG emissions are also increasing, making the difference between companies with and without targets even larger,” the study notes.

For 18 of the 50 companies included in the report, it wasn’t possible to determine whether their total emissions declined between their base years and most recent year of reporting, partly because some stopped disclosing emissions since 2020, either since they never reported scope 3 emissions, or are changing their methodology.

To make it easier to assess progress, Ceres recommends disclosing scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions separately, using a clear table to show emissions data across multiple years, indicating changes to calculation methodologies or business structure, and being transparent about any uncertainties in the data.

Analysing how the companies that managed to cut their emissions did so, Ceres revealed that increased granularity can help pinpoint where to cut emissions. Setting specific targets for Forests, Land, and Agriculture (FLAG) emissions – the largest drivers of the sector’s impact – is critical too.

Meanwhile, focusing on specific emission drivers like methane – as the likes of General Mills, Kraft Heinz, and Starbucks have done via the Dairy Methane Action Alliance – can have an outsized impact on their GHG footprint and help mitigate climate risks.

Such collaborative efforts can scale the mitigation impact across the supply chain. Moreover, policy support is crucial. “Companies are increasingly publicly supporting key legislation that may lead to broader adoption of sustainable practices in the food and agriculture system that would help them achieve their goals to cut emissions and address risk,” the report reads.

What investors need to know about emissions reporting

So, how should investors interpret emission inventories in the food industry? For starters, GHG disclosures are better used as a tool to assess a business’s progress over time, rather than compare firms with each other.

“Emissions disclosures are estimates, and the degree of accuracy depends on a company’s emissions calculation methodology,” explains Ceres. Some companies are investing in robust traceability to access primary data about agricultural activity in their supply chains, others might not know the countries of origin and could be left to rely on country-level emissions instead.

Understanding a company’s changing business context – whether it’s M&A activity, changes in emissions calculation methodology, macroeconomic factors like consumer spending, or supply chain disruptions – is key to tracking its performance over time.

“Investors can ask companies to explain whether changes in emissions were due to corporate climate action or an external factor that may not lead to a substantial change in emissions once the company re-baselines its emissions inventory,” the report says. The businesses, meanwhile, should “re-baseline their emissions promptly” to allow consistent tracking.

Finally, emissions disclosures should be examined within the full context of a firm’s climate strategy. There may be some activities the company is investing in that may not be reflected in its GHG inventory yet, while there could also be supply chain activities they can’t account for yet.

This is why Climate Transition Action Plans (CTAPs) are a critical disclosure. “CTAPs provide space for companies to contextualise their emissions inventory, describe ongoing initiatives that may help them make further progress towards reducing emissions, and highlight planned future investments that will help close the gap to achieve emissions reduction targets,” the report says.

“Considering variations and uncertainties in corporate emissions disclosures, CTAPs provide more assurance to investors that companies are taking steps to mitigate the financial risks associated with climate change and [have] concrete strategies in place to reduce emissions and future-proof their businesses to thrive in a low-carbon economy.”