Blue Horizon: Why The Food Tech Investor Gave Up Fund Management To Build a Giga Protein Factory in The Desert

12 Mins Read

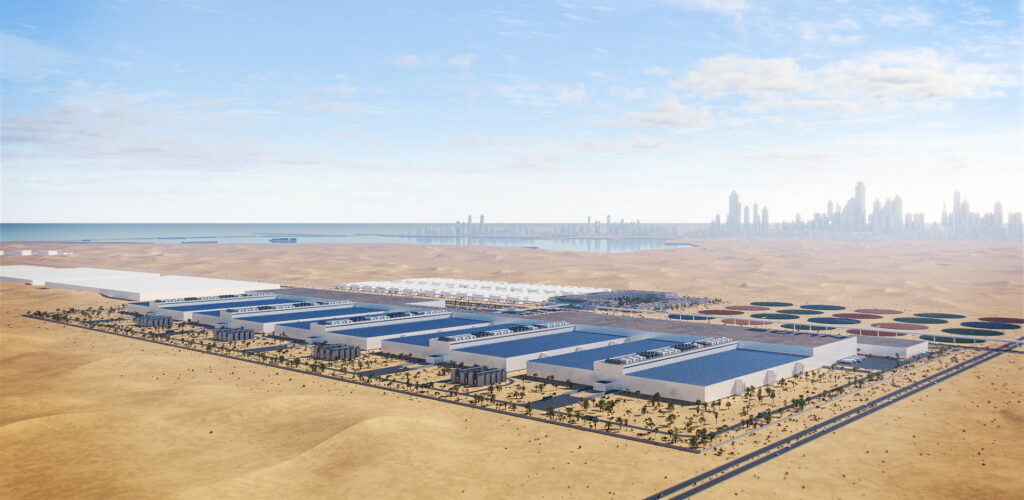

Leading future food industry investor Blue Horizon is pivoting from fund management to manufacturing, starting with a Giga Protein Factory in the Arabian desert. Here’s why.

Just over a year ago, alternative protein fund leader Blue Horizon pulled the plug on its growth fund amidst changes in the venture capital landscape and an internal dispute that had led to complications.

Fast-forward to June 2024: agrifood VC platform AgFunder announced in a social media post that it was taking over the management of Blue Horizon’s growth fund effective immediately. The update stated that Blue Horizon had “exited the investment advisory sector”.

According to the announcement, the fund’s limited partners (LPs) would “gain access to AgFunder’s global network, with offices in Silicon Valley, London, and Singapore” and “benefit from the resources provided by AgFunderNews, comprehensive research, and GAIA, AgFunder’s proprietary database and AI platform, which includes over 60,000 agtech and foodtech startups.”

Blue Horizon, meanwhile, said it was pivoting away from asset management to focus on core operations and manufacturing via large-scale ‘Giga Protein Factories’ under a new entity, dubbed NUOS (NUtrition Operating System), in a bid to “accelerate the global transition to a sustainable food system”.

It represents a significant shift in the alternative protein and future food investor space. Since its founding by Swiss businessman Roger Lienhard in 2016, Zurich-based Blue Horizon has been a seminal fund in the sector.

The team told Green Queen that over the past eight years, they looked at over 7,000 companies and startups, resulting in over 100 investments in many of the best-known names in the food and climate space, including Atomo, Eat Just, Finless Foods, Impossible Foods, Mosa Meat, Beyond Meat, and Wild Earth.

But the seed for change came when Blue Horizon began raising the growth fund – the firm realised that the category wasn’t mature enough to warrant growth equity capital.

According to Blue Horizon’s founders, the future food industry was entering the Gartner hype cycle, and concern around pricing, taste and health came to the fore, which led the conventional meat and dairy industry to mobilise and launch anti-plant-based meat campaigns. Subsequently, mainstream investors became nervous and the alternative protein sector fell into what the firm calls a “capital chasm”, a bottleneck that impeded the industry’s progress.

Blue Horizon told Green Queen they couldn’t break the cycle, ending up with only a $100 million raise after three years of efforts for their first growth fund (reports suggest the firm was targeting multiples of this sum).

Behind the scenes, there were other complications. The firm’s fund management business had faced hurdles despite raising capital, and a dispute with one key executive of the venture fund rattled LPs’ confidence, resulting in its liquidation.

“Yes, there have been tensions,” says Hector Freitas, partner and head of business development at Blue Horizon. “But that’s history.”

After much soul searching, Blue Horizon made the decision to scale back its fund management business – the firm transferred the growth fund to AgFunder – and recalibrate its employee base with an eye toward the future.

AgFunder takes on growth fund

Founded in 2013 by Michael Dean and Rob Leclerc, AgFunder is a leading global early-stage investor in food and agriculture with a portfolio of nearly 100 agrifood tech companies across six continents.

Last month, AgFunder closed its fourth early-stage fund on $102M, surpassing its target. It has already deployed a third of this fund, supporting startups like jitter-free coffee brand Rarebird and ketone-rich energy drink maker Key.

The takeover of Blue Horizon’s fund brings its total managed assets to $300M and adds a growth-stage portfolio to the firm.

“We’ve always intended to have [a growth fund], but the market needed to mature and there have been limited viable opportunities for growth stage investing until fairly recently,” Dean told Green Queen.

“With our network and AI-driven discovery platform, we have been particularly strong with early-stage investing, which also offers the best opportunity for high multiple returns – but with a maturing portfolio, we’ve always intended to have a growth strategy, and this deal with Blue Horizon gave us the opportunity to dive in sooner than later,” he added.

Discussions about Blue Horizon’s fund management began because the two funds share a limited partner. “The anchor investor in Blue Horizon is also an anchor investor in our fund,” he shared. “They approached me to see if AgFunder would be interested in taking over the Blue Horizon growth fund, and facilitated the introduction last September. So it took around seven to eight months to close.”

Would AgFunder use the funds to invest in its existing early-stage portfolio companies? “We have a good number of portfolio companies maturing nicely who will be going out for their Series B+ soon, and we’ll certainly take the best of those opportunities to our LPAC [Limited Partner Advisory Committee] for consideration [under the growth fund],” Dean said, after confirming that roughly 50% of the fund is left to disburse.

Freitas says he is confident that AgFunder will do right by the fund. “The [growth] fund is now under control of the LPs.[It’s] super important to make sure that the LPs are being looked after in the right way,” he says in an interview with Green Queen. “I’m sure they [AgFunder] will do something really good with the fund going forward.”

Blue Horizon taps into its true DNA

The focus is now on NUOS, which is described on its website as “the world’s leading contract development and manufacturing organization (CDMO) facility for producing alternative proteins at scale”. It’s an extension of Blue Horizon’s goal to transition the world to a sustainable food system.

Freitas, alongside Lienhard and CEO Björn Witte, is part of Blue Horizon’s management team, and says the development of NUOS is one of his key responsibilities.

He frames the latest activity at Blue Horizon as the result of a long-term master plan with three main verticals, with the first revolving around innovation: “One of our master plans is our innovation vertical – Blue Horizon has always stood for accelerating the transition into a sustainable food system.”

Blue Horizon’s smart protein journey started with backing alternative protein innovation, which involved seeding the early-stage funders – “meet the founders, help them with capital, and support them to grow”, as Freitas puts it. “Since the inception of Blue Horizon, we have done close to 100 investments in the alternative protein space.”

Further, he points out that the firm has had a handful of successful exits to its name, something that’s “quite unusual in the current market environment”. The latest example is New Roots, the Swiss vegan cheese company (as per Blue Horizon’s own website).

Blue Horizon began by making investments off its balance sheet, Freitas tells Green Queen, about the firm’s origins. “[First}, we started with balance sheet investments, which was followed by the inception of the funds. We started the venture capital fund, and we started the growth fund,” he says, suggesting that operational excellence has been one of the firm’s strengths.

The firm was one of the most supportive fund partners in the alternative protein space, he adds, going above and beyond a typical venture capital role. He points to a dedicated content and social media team based in Los Angeles whose sole job was to assist Blue Horizon startups as an example. “That’s how we supported our portfolio.”

Green Queen spoke to at least three founders whose companies were seed-funded by Blue Horizon who characterised the fund’s team as “very supportive of founders,” with both noting how important the team was to the broader alternative protein ecosystem.

Freitas says that Blue Horizon will continue to invest in innovation, though not at the same pace. “The adjustment of strategy is that we have decided to exit the investment advisory side of the business given the market development in our industry over the last two years,” says Freitas. “It just does not seem to work well for us.”

Covering the whole spectrum from early seed to fund advisory was “not our DNA. Our DNA is being entrepreneurial,” he explains. “That’s where we see the biggest impact,” he says when asked why Blue Horizon is pivoting to driving operational businesses. “That’s where we see the biggest need.”

Phase two: consolidation

The second vertical involved the execution of a consolidation strategy. Freitas says that while plant-based meat companies such as Like Meat, Planted or Daring tend to become very successful in their home markets quite quickly, it’s when the startups start expanding geographically that things get complicated.

“It’s still food,” he says. “It’s not an app that goes from one phone to the other,” noting the challenges of regulations and logistics for tangible goods like plant-based meat, challenges alien to software startups and their investors.

For Lienhard and his team, the “early sparks were failing to create the fire” – products were costly, they weren’t getting tastier fast enough, and the startups were too small for the impact needed. To set the stage for large-scale transition, Blue Horizon set up a special purpose vehicle (SPV) to fundraise and bring together “some of the most promising players out there”.

Blue Horizon tells Green Queen that the firm saw an opportunity to break the fragmentation cycle and consolidate some of the sector’s leading players into one holding company, which would benefit from tailwinds in the market, world-class products, consolidated operations and a credible leadership team.

That formed the basis of Livekindly Collective, which launched in 2020 with $200M in funding (later raising a $135M convertible round and a $200M Series B). Claimed to be the world’s third-largest alternative protein company, it’s essentially a roll-up of plant-based portfolio brands including Like Meat, Fry’s, Oumph!, No Meat, Dutch Weedburger, and later Alpha Foods, which allowed for economies of scale on R&D, production, distribution and marketing.

Giga protein factories and the Tesla model

The third vertical of the master plan is all about managing costs and expectations. “Up until 2022, there was ‘an early hype’; and hope in our market of gaining fast traction,” says Freitas. “Several funding rounds and funds came into the picture, Beyond Meat went public, and everyone was talking about the plant-based sector growing rapidly.”

But when the hype cools down, people look to make changes. “If you’re tight on money, you tend to go for the cheapest protein you can find in the supermarket, and the cheapest protein is still meat,” he says.

Plant-based meat still comes at a premium – in the US, it is 77% more expensive on average than conventional meat. To bridge this gap, Blue Horizon is taking inspiration from Elon Musk’s Tesla Gigafactory EV playbook in Nevada: build on a large scale in the desert, with optimum costs for energy, land, labour and logistics; involve people who care about sustainability; and focus on food security.

“We did very detailed calculations over the last 18 months… [and] realised that we will be able to undercut the lowest price of chicken breast of JBS meat from Brazil or Thailand,” says Freitas.

Just like EVs are going from highly prized (and priced) luxuries to gradual mass-market adoption, for alternative proteins to truly reach the mainstream and meet demand, the unit economics needs to compete with meat.

The first of these giga protein factories will be in the Middle East, which would be able to produce a million tonnes of product each year. “We want to be the home for alternative protein production going forward. And establishing in the Middle East has a lot of benefits,” Freitas states. “Capital, of course, but also a willingness [from local governments] to be in this space.”

When the news was announced, Witte – who is the chairman of NUOS – said the company was looking for “the right partner who shares the vision, mission and has the ecosystem to drive a global transition”, and the Abu Dhabi government turned out to be the ideal fit.

“Amongst all of the nations’ proposals NUOS received, it was clear from the outset that Abu Dhabi would be the natural partner. Through a combination of their vision, commitment, local infrastructure and long-term partnership appetite we felt that we could… create the gold standard for the food industry globally,” Witte added.

An ‘Innovation Academy’ to reach price parity

Some supermarkets have already made major strides towards price parity via their private-label ranges, with Lidl in Germany and other EU markets being the most notable example. Why can’t the sector have more such wins?

“The Lidl campaign was amazing… putting alternative proteins next to meat at the same price on the shelves. It looked super cool to start with. But in the end, products were not good or tasty enough yet to attract repeat buyers,” he says. [Editor’s note: Lidl said the campaign helped increase sales by 30% over six months.]

“There are some products out there that are really amazing. Look at Burger King: they’re selling plant-based chicken nuggets at the same price as meat. They get closer to their sustainability targets – being one key driver, but they’re probably not making enough margin yet.”

Getting taste and texture right is crucial, as is cleaning up ingredient labels. He alludes to the constant headlines criticising Beyond Meat’s supposed long ingredient lists, adding that nobody talks about what goes into the minced meat found in supermarkets. “It’s often an unfair comparison. But that’s how it works,” says Freitas. “Constant development needs to be done because our minds are so conditioned to meat.”

It’s why Blue Horizon is creating an Innovation Academy next to the gigafactory, which would allow it to invest in R&D for companies and drive prices down. While price is important to the end consumer, Freitas believes it’s probably even more crucial for B2B customers.

“If you can give a retailer or a QSR more margin against an equivalent product on a plant-based basis… they will be able to sell it,” he says. “They will place it correctly, and then consumers will take it on.”

Freitas adds: “Our strength is being close to the founders, being close to operations, being close to building infrastructure, and creating ideas [about] what the next step can be so our industry is growing… When you are on the operational side, you constantly have to be in a fight so you have a better chance [when] sitting in the driver’s seat, and steering food chains in the right direction.”

NUOS breaks ground in 2025, aiming to solve what it describes as the “great bottleneck” with the “great unlock” for plant-based meats, by enabling the upsurge in the S curve and the leap into mass adoption.

As Lienhard puts it: “The unlock for the industry is building something that can help startups accelerate and scale.”

This article was updated to add new information.

Disclaimer: NUOS is a content partner for Green Queen’s newsletter Green Queen Gulf.