Plant-Based Meat Labelling Faces Respite in Belgium, But Alt-Milk Taxes Hurt Local Brand

6 Mins Read

Belgium is halting the establishment of guidelines against plant-based meat labelling after continued disagreement among stakeholders, but its higher VAT on milk alternatives is hurting the sector, especially one homegrown brand.

The plant-based labelling war in Belgium is – for now – over, with ‘vegetarian steaks’ and ‘vegan burgers’ all fair game after the country’s lawmakers failed to reach a consensus on the subject.

Following political discussions dating back to 2022, economy minister Pierre-Yves Dermagne has announced that the government has halted its process of establishing guidelines on the labelling of meatless food products, owing to widespread disagreement on the topic.

But while that may be good news, Belgium’s stance on plant-based milk taxes is worrying, and – in the case of the company – potentially fatal.

Why Belgium has paused its plant-based meat labelling guidance

In 2020, the EU decided to vote against a proposed labelling ban for plant-based meat products, which led to a working group comprising Boerenbond, the National Union of Butchers, Bacon Butchers and Caterers, the General Farmers’ Syndicate, the Federation of Meat Producers, ProVeg International, and others, which sought to develop “clear guidelines” for plant-based labels. The group used the common argument of consumer confusion, arguing that companies can’t use meat-related terms for alternative products.

It sparked discussions that have lasted years, as well as backlash from plant-based advocacy groups the Good Food Institute Europe, the European Vegetarian Union, and ProVeg. They have urged the Belgian government to reject these guidelines, claiming that they disrespect consumers and endanger market unity in the EU.

“We feared that very restrictive guidelines regarding permitted vegetarian names would seriously compromise the accessibility and promotion of vegetarian food – which we really need to work on in the context of the fight against global warming,” said Green MP Barbara Creemers. Touching upon the consumer confusion aspect, she added: “What is the worst that can happen? That you come home with a bowl of vegetarian chicken cubes when you thought it contained real chicken?”

Creemers was told by Dermagne – who, alongside agriculture minister David Clarinval and state secretary for consumer protection Alexia Bertrand, was responsible for this issue – that there would be no new Belgian guidelines on plant-based meat labels. “There is still great dissonance between the various stakeholders regarding the guide with guidelines that has been drawn up,” Dermagne said, according to Nieuwsblad.

The guidelines that were drawn up were actually discussed at the cabinet level too. “But there is no political consensus on its publication, which I think is a shame,” the economy minister added.

“Whilst the process for developing the guideline has not officially changed, we believe it is unlikely to get any further before the next election [in June],” said ProVeg Belgium communications manager Fien Louwagie. “We hope that, post-election, the new Government acknowledges that consumers are simply not confused by plant-based foods carrying ‘meaty’ names and abandons the development of the guidelines altogether.”

Other European countries have been successful in efforts to ban the use of meat-related terms on plant-based products, most recently France and Italy. Similar discourse is ongoing in Poland. Meanwhile, Switzerland ruled against such a legislation, with a court announcing that such labels aren’t deceptive to consumers.

Discriminatory taxes leave local alt-milk brand reeling

While the halting of the process is a positive sign for plant-based advocates, Belgium’s “fiscal discrimination” against plant-based milk is a major hurdle. Currently, most drinks are subject to excise duties and packaging taxes, which amount to 22 cents for sweetened and 17 cents for unsweetened beverages. Three products are exempt from these, though: cow’s milk, soy milk and rice milk.

However, some companies aiming to come up with even more climate-friendly alternatives to rice or soy (such as pea or oat) are finding it difficult to understand why they’re treated any differently. One of them is pea milk maker Top Toh, which last year faced a bill of €30,000 in overdue excise duties, followed by a fine of €10,000.

“I had no idea we had to pay excise taxes,” Tip Toh founder Arnaud Muylaert told De Tijd. “That invoice was a very unpleasant surprise. €40,000 is a lot for a company with a turnover of €200,000.” He added: “Why does the government impose excise duties on other plant-based drinks such as oat, almond and pea milk? Especially since [they focus] on sustainability?”

The unexpected bill has forced Tip Toh to raise its prices, with its products now costing €3, which puts it at a major disadvantage, considering soy and dairy cost about €1.20 for the same amount, while most alt-milks are priced below €3. While finance minister Vincent Van Pethegem has confirmed he’s reviewing the exemption for milk, any change isn’t imminent as it would need a change in law, and will be a task for the next government.

That has left Muylaert and Tip Toh in a state of bother. “I am concerned about the survival of our company,” she said. “We can pay the excise duties, taxes and fines thanks to recently obtained subordinated loans of €180,000. But I would rather use that money for innovation and growth. We wanted to hire our first employee, but we had to cancel those plans.”

The entrepreneur has been in touch with the cabinets of lawmakers and spoke to Sammy Mahdi, president of the CD&V party. “They told me they support me, but still nothing happens. I never expected that the government would oppose our project,” he said.

It’s not just small startups that are calling for a change. Danone, parent company of Alpro, Europe’s leading plant-based dairy producer, is also in the same boat. “There needs to be harmonization,” said Danone communications and sustainability director Nathalie Guillaume. “Our society is undergoing a sustainability transition. A flexitarian diet of dairy and plant-based alternatives is the future. The price must be accessible. Therefore, there should be no discrimination in the valuation of both types of milk drinks.”

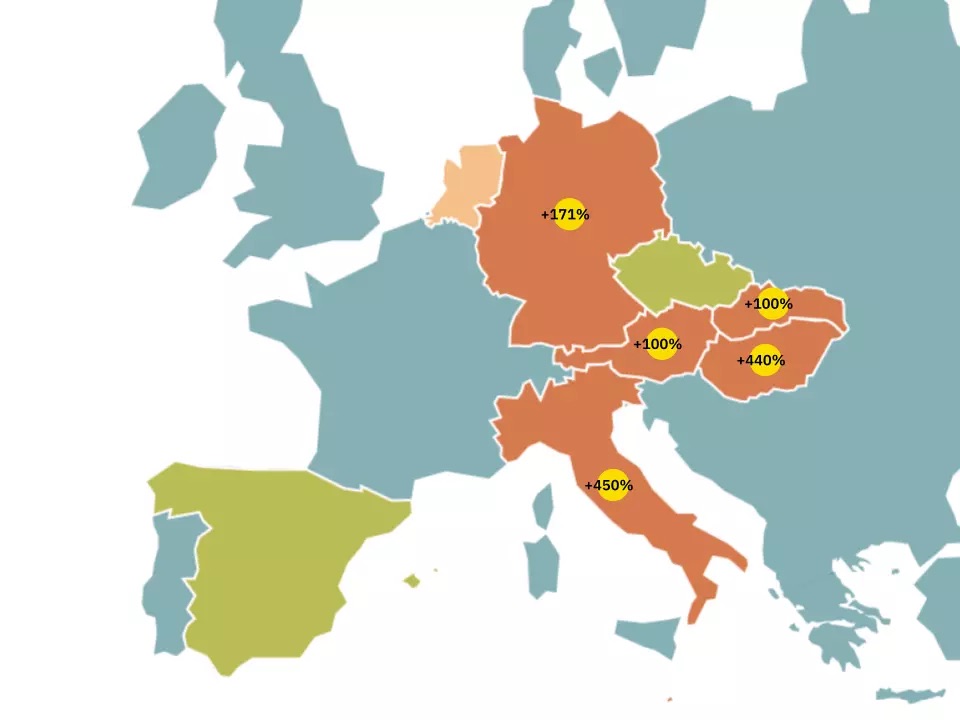

Belgium isn’t the only country with disproportionate taxes on plant-based dairy. In Germany, vegan alternatives are charged 19%, versus 7% for dairy (though there are calls for parity), Hungary has a 22% levy on plant-based and 5% tax on conventional dairy, while Italy similarly imposed 22% and 4%, respectively. The Netherlands, meanwhile, is going backwards: it previously carried an identical VAT rate of 9%, but new rules mean a 196% increase in alt-milk taxes (except soy).

But Belgium can follow the lead of the Czech Republic, which closed the gap between the tax laid on cow’s milk and plant-based alternatives – both now carry a 10% levy. Greece has also reduced its plant-based milk VAT from 24% to parity with cow’s milk (13%) now. There’s a lot resting on Belgium’s upcoming elections.