Banks Are Retreating from ESG, But They Play A Key Role in Bridging the Nature Finance Gap

4 Mins Read

As banks and investment funds move away from ESG policies, JP Morgan Chase’s biodiversity head says funding nature-based solutions is key.

It has been over six months since America’s four biggest banks left a framework that assessed the environmental, social and governance risks of their investments.

Bank of America, Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo all withdrew from the Equator Principles, a set of minimum standards and safeguards set up by the banking industry in 2003 to identify and manage the potential ESG impacts of financing high-polluting projects (like fossil fuel extraction and mining).

The move was the latest example of US banks rolling back their climate commitments in the wake of Republican states warning that participation in ESG initiatives could breach antitrust rules and threatening to boycott banks who do so.

But as global leaders convened in Cali, Colombia for the UN’s ongoing biodiversity COP16, one of these banks has acknowledged the importance of incorporating ESG principles in their investment activities to close the global nature finance gap.

JPMorgan Chase highlights nature finance gap, but must do more itself

Speaking to Semafor’s Net Zero vertical last week, JPMorgan Chase’s head of nature and biodiversity, Gwen Yu, explained what banks need to do to support biodiversity.

“We’ve seen a significant increase in client demand for products that incorporate nature, so we’re excited to be part of these global dialogues and share our expertise on how banks can help facilitate capital towards nature-related projects,” she said. “The nature funding gap is near $700B, and filling that will require both the public and private sector to find innovative ways to enable investment into this space.”

Yu added: “Private capital for biodiversity is still extremely nascent, so the finance sector has an opportunity to build on what we know works from a sustainable finance perspective and adapt it for biodiversity, while also looking for new ways to expand our book of business.”

Her comments came just as JPMorgan Chase hired Sarah Kapnick, the former presidentially appointed chief scientist of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, who rejoined the bank as its global head of climate advisory. She is tasked with helping clients “realise the economic opportunities of the transition to a low-carbon economy”.

These developments signify that JPMorgan Chase understands the financial sector’s responsibility to nature and the environment. But that said, it needs to do a lot more, by doing a lot less.

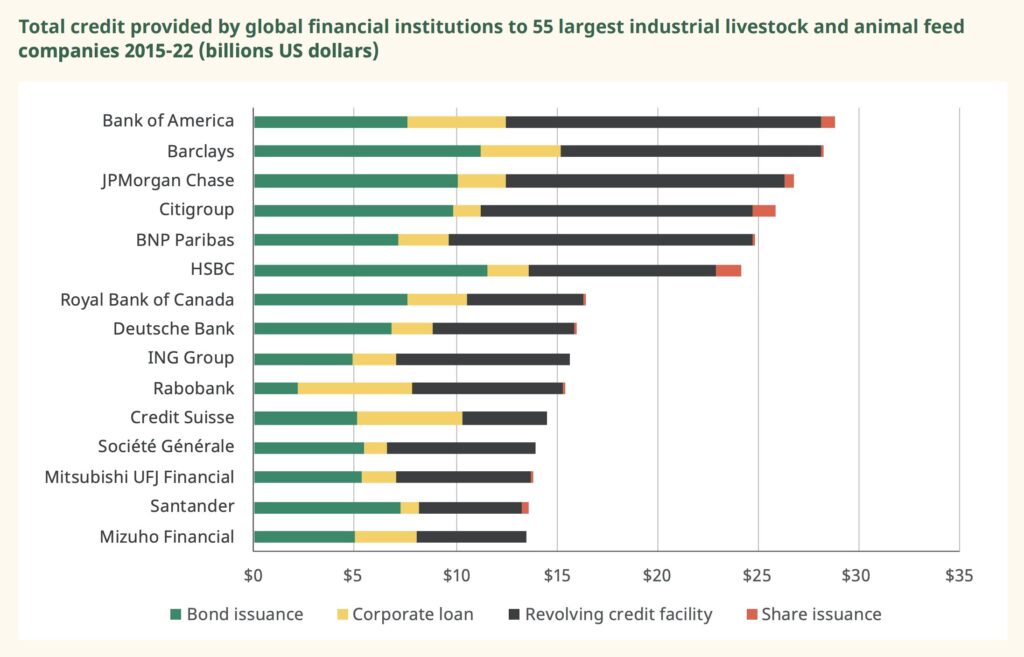

Along with Bank of America and Citigroup, it accounted for 55% of the US financial industry’s financing of meat, dairy and animal feed corporations between 2016 and 2023. Its investments in this space were linked with the third-highest amount of emissions in the US.

Cargill, ADM, Bunge and Nestlé made up 86% of JPMorgan Chase’s financed emissions in this period, and dollar for dollar, its livestock emissions intensities were four times higher than auto manufacturing and nine times more than operational oil and gas.

Similar research suggested that it was the third-largest creditor of livestock producers from 2015-22, dishing our $27B to these companies. These reports have led to over 100 organisations writing a letter to urge banks to withdraw their financial support of the planet-harming animal agriculture industry.

Biodiversity funding needs ‘practically a rounding error’

In her chat with Semafor, Yu mentioned an important number: $700B. This is the estimated global biodiversity funding gap calculated by experts from the Paulson Institute, The Nature Conservancy, and the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability.

In the seminal 2020 Financing Nature report, they looked at how much is currently spent on protecting nature, and how much is needed annually in the next decade. The exact number, $711B on average per year, may seem like a lot, but it is less than 1% of the global GDP, which is higher than $100T.

That is lower than what the world spends on cigarettes or soft drinks every year. “It is practically a rounding error compared with the trillions of dollars that world governments currently inject into their economies through stimulus programmes or the tens of trillions in private assets around the world,” the Paulson Institute noted.

The report also found that while financial flows into these efforts had tripled from 2012 to 2019, spending on agricultural, forestry and fishery subsidies – all of which degrade nature – was at least two to four times greater.

Similarly, at the COP28 climate summit in Dubai last year, the UNEP’s State of Finance for Nature study revealed that public and private sector funding of activities that directly harm nature amount to nearly $7T annually, 35 times higher than than the $200B spent on nature-based solutions.

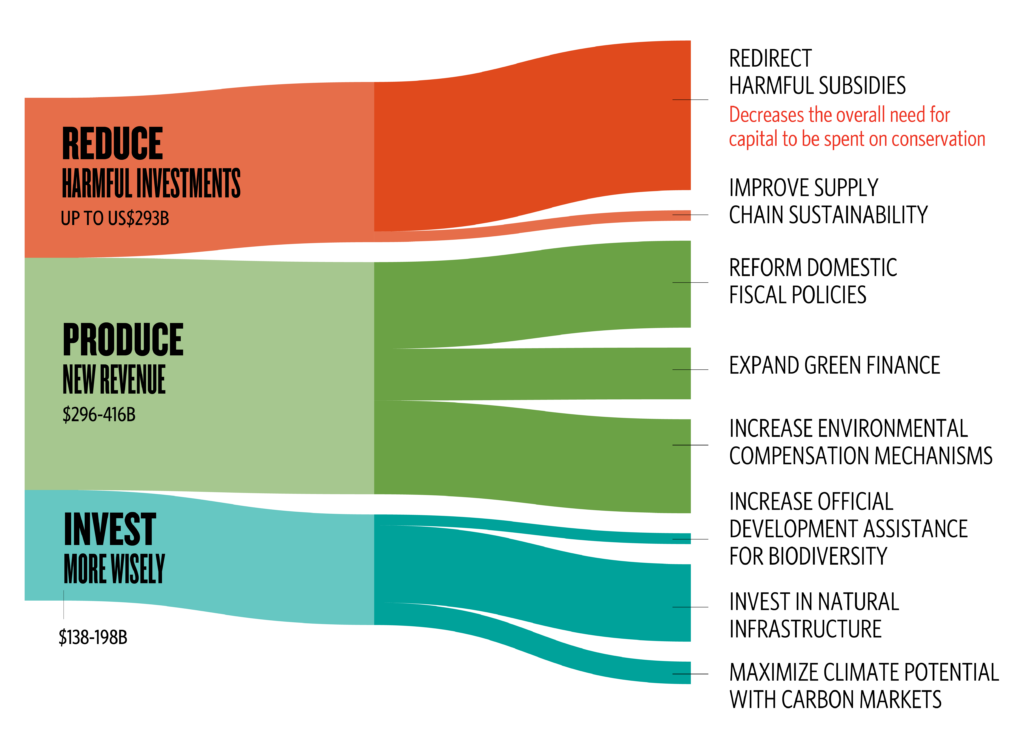

The Financing Nature report suggested that half of the nature finance gap can actually be closed with no new investments – instead, this can be addressed by better deployment of existing funds and smarter policy and investment choices.

The authors called on governments and stakeholders to redirect harmful agricultural subsidies, improve supply chain sustainability, introduce taxes to discourage nature-harming activities, expand development aid to biodiversity-rich nations, and create investments for banks and financial institutions (such as JPMorgan Chase) to invest in green products and services.