Cash Cows: Banks Have Financed Over Half a Trillion Dollars to Increase Meat & Dairy Production Since the 2015 Paris Agreement

6 Mins Read

Since world leaders signed the landmark Paris Agreement in 2015, banks and financial institutions have credited livestock producers with $615B to increase meat and dairy production, according to a new study.

It’s not just public funding propelling the meat and dairy industry forward and widening the gap with plant-based meat. While VCs have deserted the food tech and alternative protein sector lately, private equity firms and banks have provided livestock companies with more than half a trillion dollars in credits to boost animal-derived food production.

Globally, meat production grew by 9% from 2015-21, while milk production saw a 13% hike in that period. It meant we produced five times more meat and three times more milk since 1961. And according to the UN FAO, the demand for animal-based foods will increase by another 20% by 2050.

This will be fuelled by banks and financiers that have been beefing up the wallets of the animal agriculture sector, having provided $615B in credits to the world’s 55 largest livestock companies since 2015, according to a new report by agrifood campaigner Feedback International. Titled Still Butchering the Planet, it’s an update on a 2020 report that first analysed the flow of capital in this space.

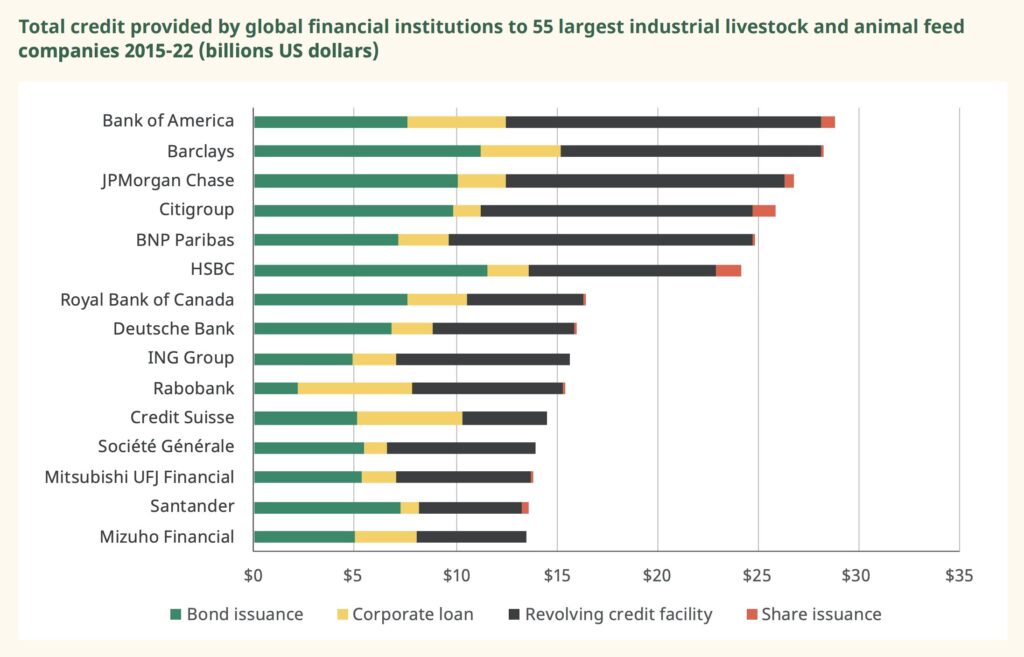

Credit is designed to help companies expand, and has helped drive the “huge and unsustainable increase” in global meat and dairy production over the last decade. The money has been provided by the likes of Barclays, Bank of America, HSBC, JPMorgan Chase and BlackRock, to name a few, and amounts to an average of $76.9B per year, helping companies that have the capacity to slaughter 44 million chickens, nearly 200,000 cattle, and 639,000 pigs every day.

These institutions lent $89B in corporate loans, underwrote $248B in bond issuances and $24B in share issuances, and provided over $254B in revolving credit facilities (which essentially work as a company credit card). As of March 2023, $288B in shareholdings and $35.5B in bond holdings were invested in these companies.

All this money contributes to a sector that causes an estimated $8.5T in externalised health and climate costs, disproportionally affects poorer countries in the Global South, and is responsible for between 11-19.6% of global emissions. “Expansion of meat and dairy production is completely at odds with the imperative to restrict global temperature rise in order to avert catastrophic climate change,” the report states.

Bank of America the worst offender, JBS the largest beneficiary

The biggest creditors to livestock companies between 2015 and 2022 were Bank of America (which shell out nearly $29B), Barclays ($28B) and JPMorgan Chase ($27B), while the largest investors were BlackRock ($38B), Vanguard ($24B) and Capital Group ($21B).

JBS, the world’s largest meat processor and highest-emitting livestock company, is also the biggest beneficiary, receiving more than $20B from these organisations, spearheaded by Barclays (which has provided it with $6.7B). Fellow meat giant Tyson Foods received $18B, with Morgan Stanley being the biggest creditor at $5.2B, while Cargill secured $19B, with BNP Paribas injecting the most capital at $4.5B.

In terms of the milk sector, Dairy Farmers of America was on the receiving end of around $5B, an amount led by Wells Fargo’s $1.3B investment. Fonterra, New Zealand’s largest company, got over $3B, with ANZ being its biggest lender at $900M.

Feedback Global notes that none of these companies have “plans to substantially reduce their livestock numbers”, with most doubling down on initiatives to increase production. For example, JBS – which has been under heavy scrutiny that has delayed its plans for an IPO – has laid out its aim for a 70% increase in global animal protein consumption by 2050, which the report says is “impossible if we are to remain within planetary boundaries”.

In fact, industrial meat and dairy companies have intensified their lobbying against any reductions in meat and dairy production and consumption, despite calls from climate scientists to reduce the amount of animal protein we’re eating. Just earlier this month, a survey of 210 academics and experts revealed that to meet the 1.5°C goal, livestock emissions must peak by next year, and they need to be halved by 2030, with high- and middle-income countries needing to eat substantially more plant-based foods.

It’s well-documented that poorer countries in the Global South are much more adversely affected by climate change than richer nations in the North. Here’s a thinker: the Global North is responsible for 92% of our excess emissions, but 91% of all extreme-weather-related deaths occur in developing countries mostly in the Global South. This is why Feedback Global says the continued injection of funds into meat and dairy companies will end up disproportionately impacting countries in the South, which in 2020 just received $21-24.5B in climate assistance funding.

Banks are going against their own policies

The report mentions that many of these investments go against these financial institutions’ policies. HSBC, for example, has an Agricultural Commodities Policy that states it will “not knowingly provide financial services to high-risk customers involved directly in or sourcing from suppliers involved in deforestation”. This included cattle ranching, but the bank was the world’s second-largest creditor to Minerva and fourth-largest to Marfrig, two of South America’s largest beef companies.

Similarly, Bank of America has a Forests Practices Policy that claims “lending proceeds are not used to finance commercial projects or operations” that lead to deforestation, but it was the fifth-largest creditor to Minerva in this period. And last year, Barclays announced it would stop financing beef or soy companies directly involved in illegal deforestation in South America, and hadn’t done so since 2021, but was still the biggest creditor to JBS between 2021-22. The company argues this doesn’t contradict its policy because it only finances JBS’s US and Europe operations.

In a statement to the Guardian, HSBC said it was important to distinguish between entities that are banking service customers and “other companies to whom we may appear to be linked to via shareholdings”. It added that it had “a stewardship plan and engagement policy” to raise concerns about companies “including deforestation risk”.

A Barclays spokesperson, meanwhile, said its financial policies “were updated in April 2023 to include restrictions on beef production and primary processing in high deforestation risk countries in South America [and require companies] to respect human rights across their operations and supply chain”.

In the four years between 2019-22, there was an overall 15% increase in financing to these livestock companies, which clearly doesn’t help the climate cause. These companies should follow the lead of institutions like De Volksbank and Australian Ethical, which have policies against investing in livestock farming, as well as Norges Bank, Aviva and Nordea Asset Management, which have either put JBS on exclusion lists, or divested from the company.

Feedback Global is asking these banks and financiers to stop all new financing to industrial livestock companies (starting with the 55 named in the report), implement agriculture-specific climate plans that recognise the need to lower livestock production and halt deforestation, engage with retailers to ensure they introduce time-bound meat and dairy reduction targets, and work with small-scale livestock farmers to lower their production and diversify into plant-based foods.

And for policymakers, the report calls on governments to regulate private banks for a phaseout from industrial livestock financing, divest public pension funds from and end funding from multilateral development banks to livestock companies within the next five years, introduce meat and emissions taxes, fund a Green New Deal, incentivise lower meat and dairy consumption, shift subsidies away from large livestock companies, and set pollution limits of water, soil and air for these producers.