5 Mins Read

A large analysis of climate change policies from across the world has found that only one in 20 has any meaningful reductions in emissions, with carbon pricing earmarked as key to success.

Despite the global commitment to cut emissions by 42% come 2030, on the road to net zero by 2050, national climate policies are largely failing, according to a new analysis.

Led by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research and the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC), the study looked at 1,450 climate change policies from 41 countries between 1998 and 2022 – together, they accounted for 81% of global emissions in 2019.

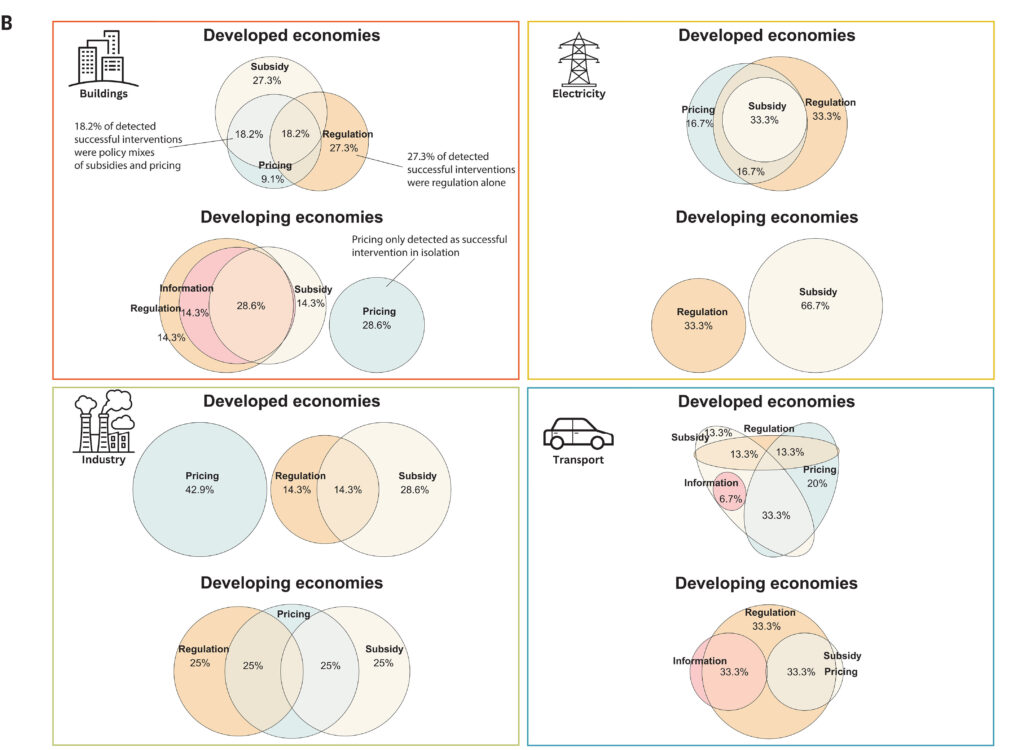

The researchers categorised the policies into four subgroups – pricing, regulations, subsidies and information – and assessed the electricity, transportation, buildings, and industry sectors in both developed and developing economies.

The results, published in the Science journal, are jarring: of the policies analysed, only 63 (or 4.3%) were found to have delivered large emissions reductions (over 5%). And even among these, the actual impact on carbon emissions was meagre.

These policies lowered emissions between 600 million tonnes and 1.8 billion tonnes. But last year alone, the world emitted 36.8 billion tonnes of the planet-heating gas, driven by pollution from fossil fuels.

Two (or more) are better than one

The study found that most policy tools – like phasing out fossil fuels, coal power plants, or combustion engines – haven’t worked on their own. Instead, they’re more likely to succeed when mixed with an energy tax or another pricing system.

“Our findings demonstrate that more policies do not necessarily equate to better outcomes. Instead, the right mix of measures is crucial,” said PIK and MCC’s Nicolas Koch, the study’s lead author, explained. “For example, subsidies or regulations alone are insufficient; only in combination with price-based instruments, such as carbon and energy taxes, can they deliver substantial emission reductions.”

For example, one of the more successful efforts came from the UK in the energy sector – its government implemented a mix of 11 different policies starting in 2012, including a phaseout of coal power plants and a pricing scheme around emissions trading. This nearly halved emissions, according to Koch.

Similarly, in the industry sector, China’s launch of seven pilot emission trading schemes reduced emissions via a combination of carbon pricing, fossil fuel subsidy cuts, and stronger mechanisms for energy efficiency investments.

Overall, the largest reduction in emissions through a climate policy came in South Africa’s building sector, where a mix of regulation, subsidies and the labelling of appliances brought emissions down by 53.8%.

In the US, the only substantial cut identified was in the transportation sector, with a combination of tax incentives and subsidies for low-emitting vehicles and CO2 efficiency standards reducing emissions by 8.2% from 2005-16. However, the recently passed Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) – the Biden-Harris administration’s signature environmental legislation, and the largest climate investment in US history – was not part of the study’s timeline.

Another notable example is Germany, whose environmental tax reform and truck toll introduction led to an 8% reduction in emissions in the early 2000s.

But experts note that pricing schemes are critical for better climate policies. “Carbon pricing puts the onus on the owners and products causing the climate crisis,” Rob Jackson, a Stanford University climate scientist not involved in the study, told the AP. “We won’t crack the climate problem in wealthier nations until the polluter pays. Other policies help, but nibble around the edges.”

Policy mixes are effective, but carbon taxes work alone too

The scientists point out that even if every major nation applied the lessons of this study and enacted successful policies, this would only close the UN emissions gap by about 26%. This gap – the difference between where global emissions are headed with current national commitments, and where they need to be to align with a 1.5°C future – is currently 23 billion tonnes.

To allow people to see these impacts for themselves, the researchers have established a public website called Climate Policy Explorer. Here, the result of the study can be viewed by choosing countries and sectors where policies have been successful. Eventually, this would also comprise the IRA.

These case studies provide insights into effective policy combinations, and demonstrate how “well-designed policy mixes depend on sectors and the development level of countries”, according to PIK’s Annika Stechemesser, a fellow lead author. “This knowledge is vital for supporting policymakers and society in the transition to climate neutrality,” she added.

The analysis informs climate policy discourse in three ways. First, it serves as empirical evidence that policy mixes are effective, countering critics who argue that a combination of policies could be subject to overlapping instruments. The research found larger emission impacts when subsidy schemes and regulatory instruments like bans, energy efficiency mandates, and labels were mixed, as opposed to a standalone implementation.

Secondly, the scientists believe that successful climate policy mixes vary by sector, and lawmakers should focus on sector-specific best practices rather than adopt a one-size-fits-all strategy. For example, carbon pricing is particularly effective as a complementary measure in the industry sector, while policy instruments work better in the building sector.

And finally, economic development dictates the efficacy of climate policies. “In sharp contrast to that of developed economies, we did not find any successful pricing intervention with large emission reductions in the electricity sector of developing economies, even though around 13% of policy adoptions or tightenings are pricing interventions,” the researchers explain.

That said, carbon or energy taxes seem to be a uniquely impactful measure, notably effective in cutting emissions on its own. “It stands out as the only policy instrument that achieves near equal or larger effect size as a stand-lone policy across all sectors,” says the study.

Denmark earlier this year announced it would begin taxing meat and dairy production from 2030, in what was the world’s first carbon tax on agriculture.