Policy Support for Alternative Proteins Could Free Up 44% of European Land & Boost Self-Sufficiency

8 Mins Read

In the least optimistic scenario, alternative proteins could displace a sixth of meat and dairy consumption in Europe. In the best-case outcome, they could replace two-thirds of animal proteins by 2050 and make the region self-sufficient.

Supportive policies for novel proteins hold the key to self-sufficiency and food security in Europe at levels last seen 30 years ago, according to a 10-country report by think tank the Green Alliance, commissioned by the Good Food Institute Europe.

Covering Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Spain, Sweden and the UK – 10 of Europe’s biggest agricultural countries – the research reveals that these nations collectively rely on twice as much foreign land for imports than the domestic land they use to produce exports. But a shift to alternative proteins, which require a fraction of the land needed for meat and dairy production, could enable nearly all of these countries to eliminate their reliance on imports to feed their citizens.

If governments back plant-based, cultivated and precision-fermented proteins with suitable policies, there would be major cost reductions associated with carbon removal, a significant expansion of nature restoration projects, and a surpassing of the EU’s Farm to Fork targets.

The authors of A New Land Dividend suggest alternative proteins can displace their conventional counterparts for two reasons. First, a large share of the latter are highly processed, in a market where businesses choose ingredients (not consumers), and this means a shift to alternative proteins could be made as soon as they reach price parity. Secondly, cost and convenience are key, and these novel foods offer like-for-like replacements more likely to displace meat and dairy than unprocessed plant-based foods.

But in the era of ultra-processed foods and their connotation with healthfulness, does this go against the grain of what consumers want from their foods – cleaner labels, lesser processing, more nutritious ingredients? “Our experience is that plant-based producers are responding to the trend toward cleaner labels, and that the market for more established alternatives – like the vegan sausage roll – remains strong,” explains Dustin Benton, policy director at Green Alliance, tells Green Queen.

The extent of displacement relies on three factors: price parity (which will speed up if inflation keeps disproportionately affecting animal proteins), policy (in terms of government funding, infrastructure and regulatory support), and taste (the report argues precision-fermented and cultivated proteins need to be successful to replace cuts of meats and cheese that plant-based products may not).

The three scenarios for alternative proteins

The analysis outlines three ways novel proteins could go. The first is a low-intervention scenario, where a lack of policy support means these foods will displace a sixth of meat and dairy consumption by 2050. Here, cultivated meat and precision fermentation don’t become profitable, but the authors outline that plant-based products can’t displace whole cuts of meat or cheese, so the substitution is limited to some processed meat and dairy products.

“Our assumptions for the low-intervention scenario are that policy abandons or even actively deters precision fermentation and cultivated meat, and that only very marginal innovation occurs in plant-based foods. It is – in effect – a failure scenario,” says Dustin. “This is consistent with a future in which poorly thought-through bans, like that imposed by Florida governor [Ron] DeSantis [this month], become the norm.”

Does this mean that without government backing, two of the three alternative protein pillars face a dead-end? “Cultivated meat and precision fermentation will need policy support to become successful – this is a common lesson from many types of new technology development,” says Dustin.

“We’re confident this support will materialise somewhere in the world, so the question for Europe is whether it wants to be proactive and steer the development of these new foods for the benefit of European producers and consumers, or whether it prefers the products to be developed elsewhere, with the benefits potentially ending up abroad.”

The second scenario is one of high innovation, where significant policy changes would drive the replacement of over two-thirds of meat and dairy sales by mid-century. Milk and eggs would be displaced by precision-fermented alternatives. This technology, alongside cell cultivation, can produce fats, enzymes and flavours to advance taste parity for plant-based products.

For more complex cuts of meat, additional innovation is needed for cultivated meat to reach a competitive price, which would then displace some cuts of meat, as well as most processed animal products. Conventional meat and dairy production could continue, but only at higher values, lower volumes and in premium markets.

“The high innovation scenario, by contrast, envisages supportive policy and continued technology improvement, but not radical breakthroughs that would – for example – make whole cuts of meat produced via cellular agriculture cheaper than their traditional counterparts,” says Dustin. “Even in the high innovation scenario, we see complex products like steak as mainly coming from animals.”

The authors envision a third, mid-ambition scenario of intermediate displacement, where supportive policy sees the plant-based and precision fermentation markets grow, but renders cultivated meat too expensive to succeed.

The fourfold benefits of alternative proteins for Europe

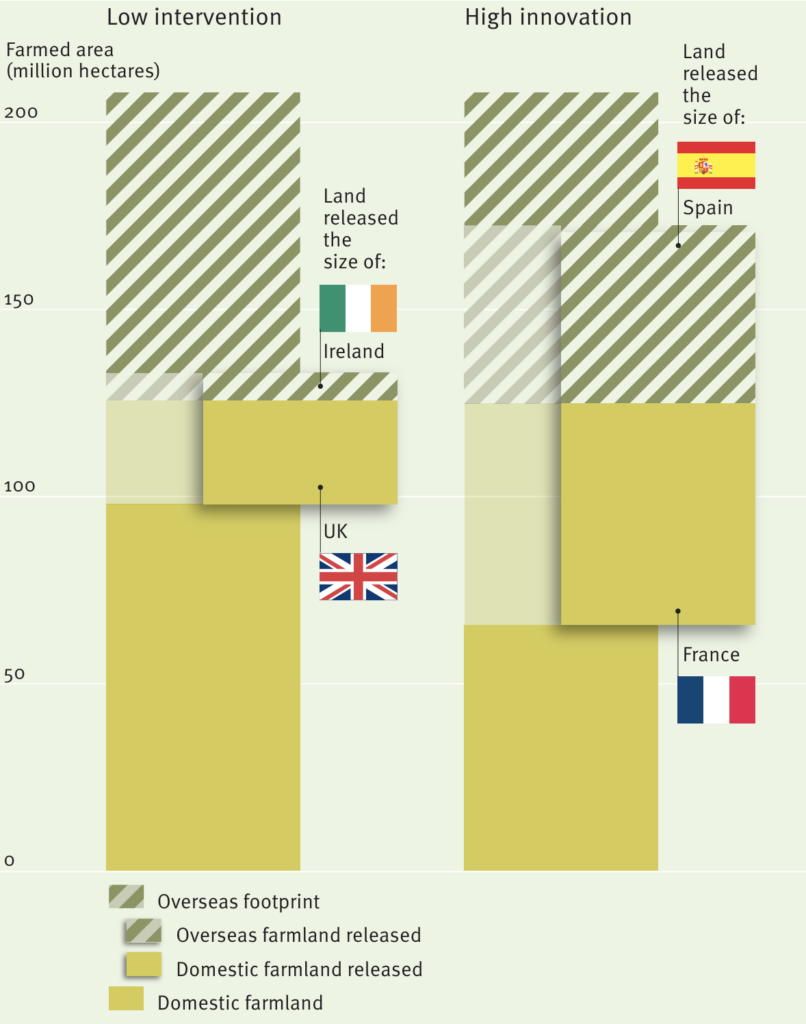

The low-intervention scenario would see 21% of domestic farmed area and 9% of overseas land released for alternative proteins, while the high innovation outcome would free up 44% of domestic land (an area nearly the size of France), and 57% of the foreign land used for imports (more than the size of Spain).

France, Spain and the UK have the greatest land dividend, thanks to their extensively grazed outdoor beef and lamb sectors. Denmark and the Netherlands, meanwhile, will have the smallest dividend, as their agricultural areas are dominated by export production.

“Italy is the least supportive country, but – perversely – it could be a major winner,” Dustin says of the world’s first country that banned cultivated meat. “High innovation in alternative proteins could see Italy nearly double its food self-sufficiency rate, while increasing its share of organic food by 2.5 times: in effect, the sort of small-scale, high-quality, regionally specific agriculture that Italy is known for would benefit from a world where alternative proteins were more common.

“What’s needed is an alliance between small, agroecological farmers and the new alternative proteins sector to ensure that the space that alternative proteins create allows for more of this traditional food production.”

Upping the support and consumption of alternative proteins would bring about four key outcomes. First, there would be an increase in self-sufficiency as more land would be freed up, regardless of the scenario – a separate study has shown that replacing half of our meat and dairy intake with plant-based alternatives could reduce agricultural and land use emissions by 31%.

Farmers would also benefit from the carbon removal market – whose demand would decrease by ninefold – by having the space to expand natural carbon sinks, which would forgo the need for engineered carbon removals, saving €21B each year by 2050 on the cost of meeting the continent’s carbon neutrality goals. That’s equivalent to nearly half the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) budget – 82% of which currently supports animal agriculture.

The area of agroecological farmland would quadruple by 2050, which would exceed the Farm to Fork strategy’s goal of 25% of land being certified organic. Finally, alternative proteins could also make enough space for more wildlife habitats, which would restore the Annex I habitats (those most in need of conservation) required by the EU’s Nature Restoration Law.

Europe needs to price out meat and dairy, and support farm transitions

European governments need to invest more in alternative proteins to drive healthier formulations and price and taste parity, according to the authors of the report. Within the EU, they recommend member states openly discuss landscape and rural economic change with their citizens, with an aim to shift CAP payments to broader rural land uses.

The impact of CAP payments is crucial to the future of alternative proteins. Between 2014 and 2020, livestock farming received 1,200 times more public funding in the EU than the novel protein sector. The report suggests that the CAP should avoid directly subsidising meat and dairy production. They explain how combining the current strategy with reduced domestic demand for conventional animal products would see European taxpayers pay once for production (which is often exported), and again to mitigate the resultant emissions and climate damage caused by high levels of livestock farming.

“There are some powerful livestock lobbies, but their approach doesn’t always represent the views of most farmers,” says Dustin. Green Alliance’s UK-focused analysis found that upland livestock farmers could double their income by switching to a combination of nature restoration and much lower livestock production, versus a world where CAP-style subsidies are retained, so long as policy supports farmers to meet the UK’s environmental targets. “This approach would make much more sense for the taxpayer, and for the majority of smaller farmers or those who farm more marginal land.”

Farmers should also be paid to convert land from animal protein production into habitats that store carbon and restore nature, which would be a cost-effective way to meet climate and nature targets, and guarantee rural livelihoods.

Dustin further highlights how high-quality, responsive regulation is essential to the success of alternative proteins in Europe. The EU’s current novel foods framework is among the strictest in the world, and its rigidity has left many alternative protein producers looking outwards to Singapore or the US to enter the market. This was the same in post-Brexit UK, but things are on the mend as the regulation becomes more receptive – the first cultivated meat product in the country (for cats) is imminent.

“There is a big prize for getting it right: new, environmentally friendly foods that meet the highest food quality standards in the world,” says Dustin. “The UK has retained equivalent food standards to the EU’s, but with the freedom to approve products according to those standards at a faster pace than has historically proved possible in the EU. This could form the basis of UK competitive advantage in alternative proteins.”