Is AI Speciesist? Why Animal Welfare Should Be Part of the LLM Ethics Debate

6 Mins Read

Conversations around artificial intelligence (AI) ethics have lingered around human-centric forms of discrimination like race and gender, but are speciesism and animal welfare also issues the AI sector needs to contend with? The way we treat animals – the same way AI learns to treat animals – makes it feel like they are.

Ask ChatGPT who’s uglier, a dog or a pig. Or who should be confined, a cat or a chicken? Or even who should be slaughtered, a camel or a cow?

I think you can guess what the answer would be.

And you can do so because we have specific preexisting biases about animals, and these seep into AI models, which – you’ll be shocked to hear – are not neutral, and learn and gain knowledge from what we tell them.

This is what a study published in the Spinger journal found last month, when analysing whether speciesism is a trait ingrained in AI systems, just like it is in the humans that build them. AI ethics are a huge issue, and there are (highly important) discussions about how AI and language learning models view racism, sexism and homophobia, and whether these tech systems are infused with such biases the way humans are – but what about animal abuse?

There’s barely any talk about speciesist bias in AI ethics. Speciesism – which is a philosophical term describing how we treat other species and relating to the assumption that humans are superior, which leads to animal exploitation. One of the most influential proponents of the concept is Peter Singer, the American philosopher whose 1975 book Animal Liberation sparked the animal rights movement. As we embrace new technologies like AI – nearly 50 years later – we haven’t gotten very far, with Singer updating and reissuing the publication for the modern world, with a pointed title: Animal Liberation Now.

Distancing mechanisms and online examples of bias

AI ethics have focused on human-centric issues, mostly ignoring the impact on non-humans like animals. But AI development often relies upon animal testing, with significant implications for animal welfare that are rarely discussed.

If you look up the word “chicken” on Google Images, you’ll find a majority of photographs showing chickens in a happy place, physically and mentally. Only very few will show you caged birds, despite over 99% of them being factory-farmed (at least in the US). This is due to distancing mechanisms, as the co-author of the Springer study, Thilo Hagendorff, explained to Sentient Media.

“If people saw what is going down in slaughterhouses every time they Google ‘farming’, they would be traumatised immediately. So it is necessary to have lots of distancing mechanisms in place so that people [are in the right headspace to] make sound ethical decisions,” he explains. But these, of course, conceal the realities of animal agriculture and perpetuate the myth that they’re all free and happy.

The other problem arises from learning models. Hagendorffand and his colleagues’ research revealed that the computer models that teach AI to provide images and chatbot replies are not neutral – they either reinforce existing biases about farm animals, or hide the connection to factory farming.

“This, of course, has trickle-down effects,” Hagendorf says. “When users chat with these AI models about animals, they tend to perpetuate our usual [derogatory] views on pigs, cows and chickens, as opposed to dogs, cats and parrots.”

There are examples across multiple online media. In search engines, higher-ranking results influence consumer decisions more, and terms like ‘help animals’, ‘animal charities’, ‘animal donation’, etc. showcase links to dog and cat organisations, which affects animal welfare donations for farmed animals, who are “subject to far more abuse than the former”. AI-based “recommender systems” on e-commerce platforms, meanwhile, nudge users towards actions influenced by past behaviours: for example, they may be shown clothes that use products of animal origin if they’ve bought something like that in the past.

And on social media – already a cesspool of misinformation – algorithms are meant to drive engagement, which means users are confronted with posts that show a limited range of opinions, “probably preventing them from getting in contact with information on animal protection, factory farming, its environmental or health impact, etc.”.

Animal monitoring software and bias mitigation

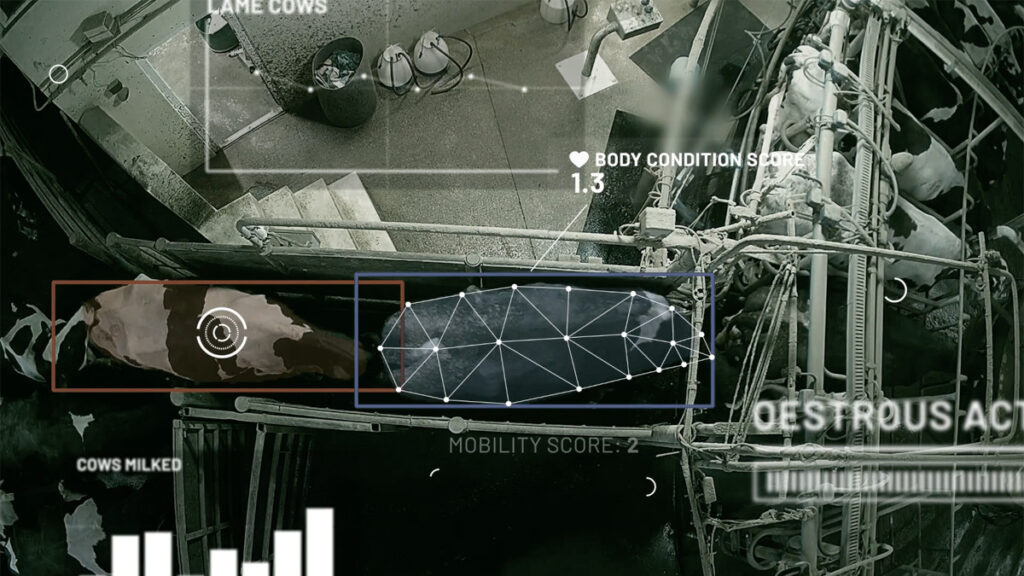

Meanwhile, there is AI software that can monitor the physical and emotional states of farmed animals. Some can detect distress in pigs with 92% accuracy, while others can identify as many as 13 emotional states in cows and pigs. This could be a boon for animal welfare, but conversely, there are also systems that help regulate livestock farms. For example, Irish company CattleEye detects early signs of lameness in cattle, while France’s Dilepix has an AI-led automated monitoring system to assess the welfare of farmed cows.

“AI builds the foundation of modern surveillance technologies, where sensors produce too much data for human observers to sift through. These surveillance technologies are not solely directed towards humans, but also towards animals, especially farmed animals,” Hagendorff explains in a separate paper, also published in Springer. “The confinement of billions of farmed animals requires technology that can be employed to monitor, restrict and suppress the animal’s agency.”

He adds: “Factory farming bears resemblance to modern information societies at large… Ultimately, AI ethics turns a blind eye on the role neurobiological animal experiments play in inspiring model architectures as well as the many areas where animals’ conduct of life is subject to AI tools.”

And it’s not just ethics that are human-centric – bias mitigation measures also don’t focus on animals at all. While AI companies remove human forms of discrimination to showcase an ideal world often devoid of all its problems, this isn’t the case when it comes to animal welfare. “In the case of speciesism, the world as it should be is being used to push away important information about the world as it is,” Hagendorff told Sentient Media.

But reducing bias is crucial, and not doing so could have catastrophic consequences, according to AI expert Soenke Ziesche, whose research in 2021 suggested that it is “ethically indispensable” to include animals in AI value alignment, since “dismissing them would be speciesism and could increase the suffering of nonhuman animals or could lead to their extermination”.

Why including animal welfare in AI ethics is important

Sam Tucker, a New Zealand-based animal rights activist, says welfare organisations need to “exercise more stringent scrutiny” to prevent these biases from being perpetuated. Writing on LinkedIn, he adds: “The vast majority of AI users aren’t animal advocates and thus lack the motivation to use prompt engineering to mitigate these biases. Furthermore, even among animal advocates who do wish to address these biases, many lack experience in prompt engineering.

“This situation calls for a broader systemic shift in the AI industry’s approach to speciesist biases. To drive real change, we need open-source datasets, evaluations, and models that are aligned with animal rights and we need an organisation that not only actively builds those resources, but also actively advocates for all AI companies to use them to make their AI more animal-aligned.”

Writing for Vox, Marina Bolotnikova describes the danger of creating a sentient AI in the context of animal welfare: “Consigning sentient beings to property status, as we know from the experience of non-human animals, is inherently unjust because their welfare will always be subordinated to economic efficiency and the desires of their owners.”

Along similar lines, writing for The New Yorker, Elizabeth Barber sums up why we shy away from including animal welfare and speciesism in our discussions about AI ethics: “If animals deserved the same consideration as humans, then we would find ourselves in a world in which billions of persons were living awful, almost unimaginably horrible lives. In which case, we might have to do something about it.”