4 Mins Read

The exacerbating effects of climate change could wreak havoc on human gut health, especially in middle- and low-income countries, according to a new study.

The growing popularity of Ozempic, GLP-1-supportive food and drink products, and documentaries like Netflix’s Hack Your Health has put gut wellness in full focus for consumers today.

For example, in 2024, Google searches for ‘gut health’ and ‘microbiome’ hiked by 35% and 31%, respectively. Awareness about fibre consumption also took centre stage, with 64% of Americans and 70% of Brits looking to increase their consumption of the nutrient.

This has coincided with a plethora of new research about what impacts the gut microbiome, and how to best keep it healthy. One new study by Michigan State University posits that climate change could worsen things for gut health, primarily by altering food quantity and quality and environmental microbiota.

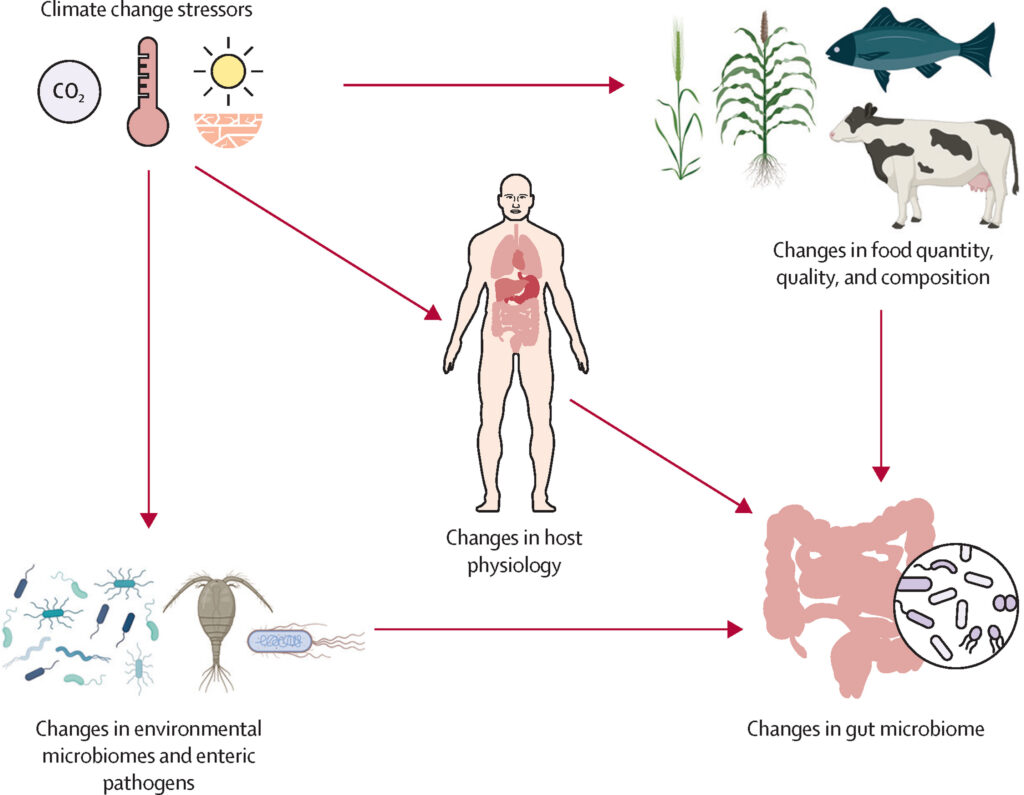

“Climate-change-induced variability in food supply, shifts in elemental and macromolecular composition of plant and animal food, the proliferation of enteric pathogens, and the direct effects of high temperatures on gut physiology might alter gut microbiota in undesirable ways, increasing the health burden of climate change,” wrote study author Elena Litchman.

How climate change could impact gut health

The research, published in The Lancet Planetary Health journal, stated that high temperatures, extreme weather events, and increased pest outbreaks can significantly decrease – or even decimate – various crop supplies, which can make famine and undernourishment more prevalent. This, in turn, would lead to extreme caloric restriction, impacting human health and gut microbiota.

Rising emissions and temperatures can reduce the nutritional quality of crops, and subsequently lower nutrient concentration and increase carbon-to-nitrogen ratios, which makes food less digestible. Current projections show that over 100 million people might become protein-deficient by 2050. “The combined effects of multiple stressors, such as high temperature and droughts, might cause further declines in protein, micronutrient, and macronutrient content in food plants,” wrote Litchman.

Heat stress can also induce complex changes in the gut, including a change in microbiota composition, higher oxygen levels, and overproduction of stress hormones – this could make people more susceptible to harmful organisms.

The body’s gastrointestinal lining becomes more permeable under heat stress, making it easier for toxins and pathogens in the digestive tract to enter the bloodstream. These changes can further disrupt important digestive and immune functions.

Moreover, changes in the consumption of meat, dairy and plants will play a role too. Overall diet diversity might be affected by changing climate and agricultural practices.

“Plant and animal varieties susceptible to climate change might be replaced by more resistant species with different nutritional qualities, either due to natural or artificial selection,” the study explained.

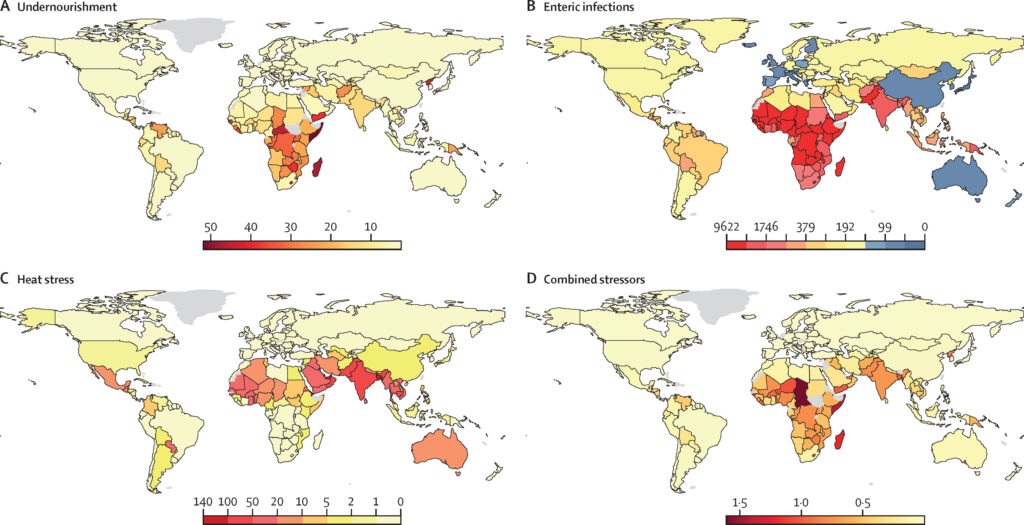

Low- and middle-income face the brunt of the impact

Litchman suggested that one implication of climate change would be a diminished ability of the body to absorb vital nutrients, and this is a problem greatly exacerbated when nutritious food is in short supply. Concerns over food security loom large in climate discourse – the global population is set to approach 10 billion by 2050, but hunger has increased consecutively for three years now.

Like the climate crisis, food security disproportionally impacts low- and middle-income countries. These nations may have fewer means to counteract food shortages, which could worsen the implications for gut health among these populations.

“The effects of food shortages and starvation can be especially severe in children in low-income countries, with malnutrition changing the gut microbiota composition,” said Litchman. “Malnutrition might be resistant to treatment, with dysbiotic gut microbial communities persisting despite interventions.”

Moreover, high temperature stress can affect the physiology of breastfeeding for both mothers and infants. Infant gut microbiome can be significantly altered here, with these changes especially relevant for populations in low- and middle-income countries with a high prevalence of breastfeeding, widening the health inequities under climate change.

The research found that selecting more climate-resilient varieties of crops could help mitigate climate change and food insecurity, as well as regulate the gut microbiome “However, if new varieties are selected to primarily maintain yield in novel climatic conditions, they might not necessarily have the same nutritional quality, thus changing dietary nutrient uptake, with potential effects on gut microbiota,” it stated.

Again, countries and communities with low purchasing power may not be able to acquire or adopt climate-resilient varieties, further widening the gap between low-income and affluent countries.

“Promoting food diversity to improve nutrition would benefit multiple aspects of human health, including the composition and functioning of gut microbiomes,” Litchman said. “Increasing diet and ecosystem diversity can improve food security globally, especially in low- and middle-income countries, and reduce the hidden hunger effect.”

Additionally, achieving high-quality sanitation is crucial for nations that already have a high enteric pathogen burden. “Effective mitigation and adaptation strategies would not be equally available across regions, countries, and communities,” the study highlighted. “However, efforts should still be made to eliminate or minimise inequities at different scales.”