Climate, Food, Health & Economic Crises Are Interlinked – What’s the Best Path Forward?

6 Mins Read

A major UN report calls out governments for ignoring the connections between biodiversity, water, food, health and climate change – and suggests how best to address these crises.

Environmental, social and economic crises like biodiversity loss, water scarcity, food insecurity, health risks, and climate change are all deeply interconnected, rendering separate efforts to address them “ineffective and counterproductive”, according to a landmark report by the UN Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

The report – known as the Nexus Assessment – found that governments are prioritising “short-term benefits and financial returns for a small number of people”, while ignoring the costs to the five nexus elements: biodiversity, water, food, health, and climate.

Approved by almost 150 countries in Windhoek, Namibia, the analysis is described as “the most ambitious scientific assessment ever undertaken of these complex interconnections”, and argues that “fragmented governance” of these elements is causing unintended consequences and stands in the way of effective action.

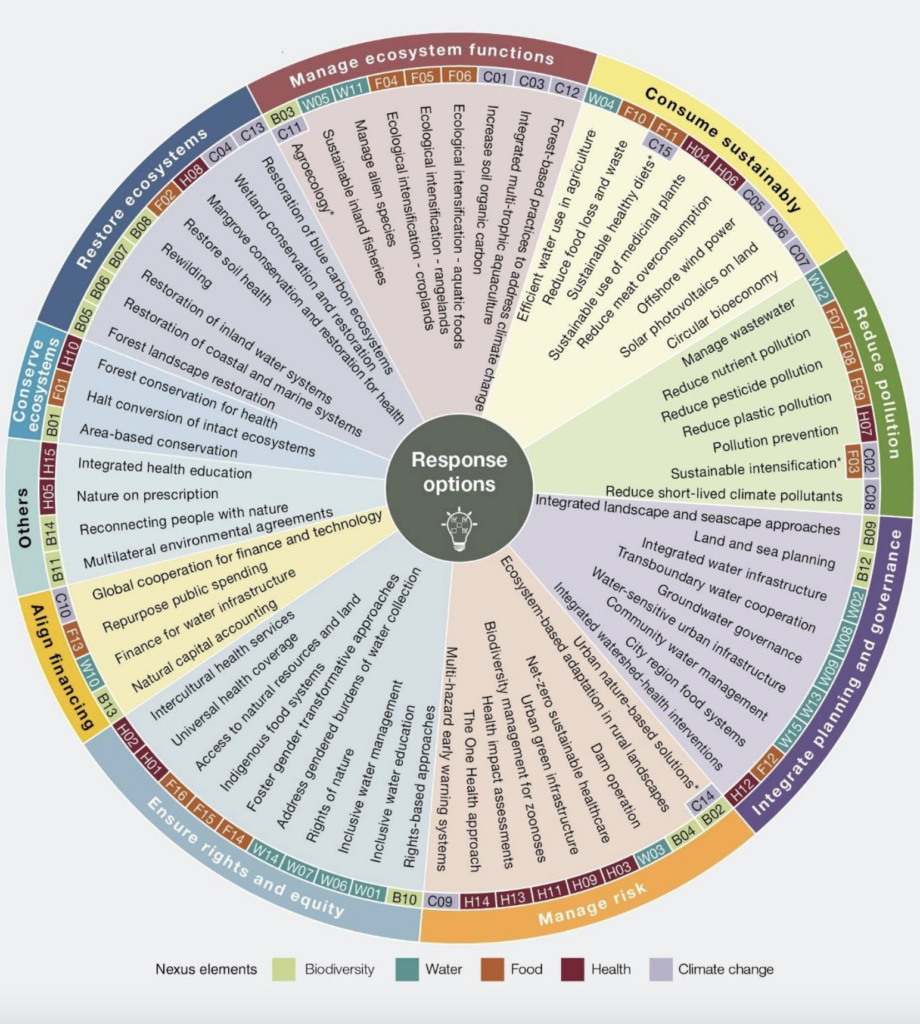

Instead, tackling these issues can maximise co-benefits for each of the nexus points, according to the IPBES, which laid out 71 “response options” to address the challenges.

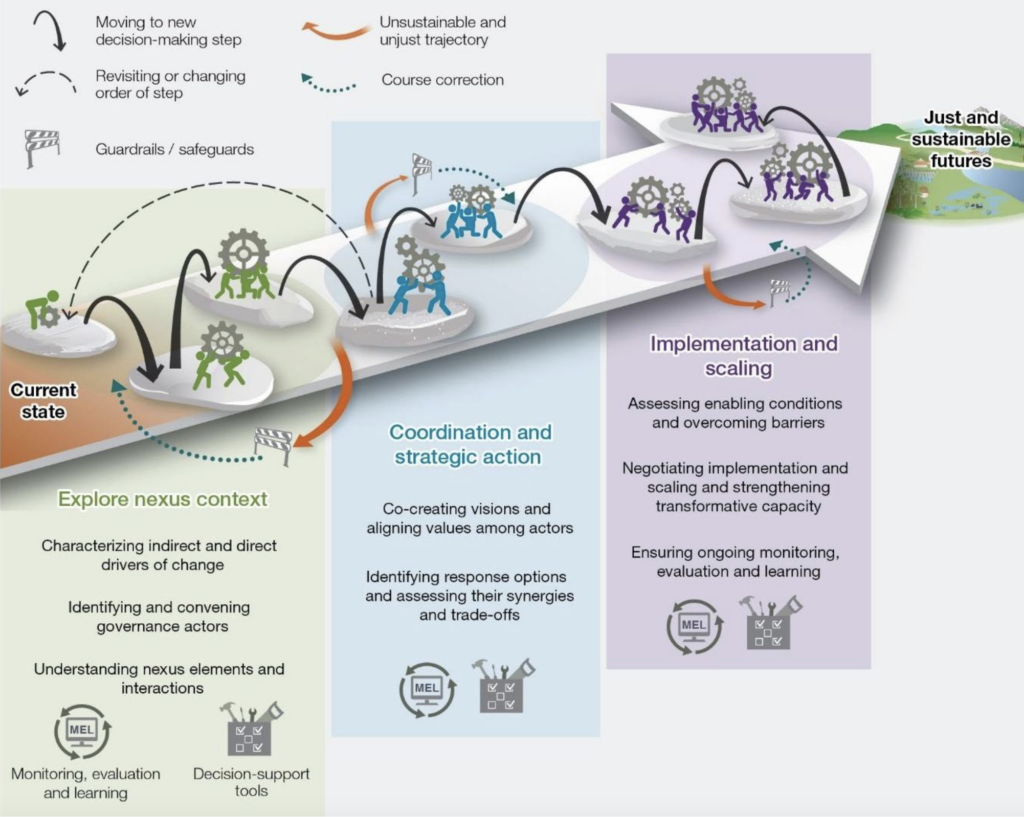

“We have to move decisions and actions beyond single-issue silos to better manage, govern and improve the impact of actions in one nexus element on other elements,” said Prof Paula Harrison, a co-chair of the Nexus Assessment.

Fellow chair Prof Pamela McElwee said that decision-makers have so far failed to hold climate-damaging actors to account. “It is estimated that the unaccounted-for costs of current approaches to economic activity – reflecting impacts on biodiversity, water, health and climate change, including from food production – are at least $10-25T per year,” she noted.

Analysing a variety of long-term climate outcomes

The Nexus Assessment suggests that for the last 30 to 50 years, 2-6% of biodiversity has decreased every decade, across every region. And today, more than half the world lives in areas experiencing the worst impacts of declines in biodiversity, water availability and food security, and increases in health risks and climate harms.

But while some regulations and research efforts have been partially successful in improving trends across the nexus elements, they’re unlikely to succeed without addressing the interconnections in a more rounded way, and tackling indirect drivers like trade and consumption.

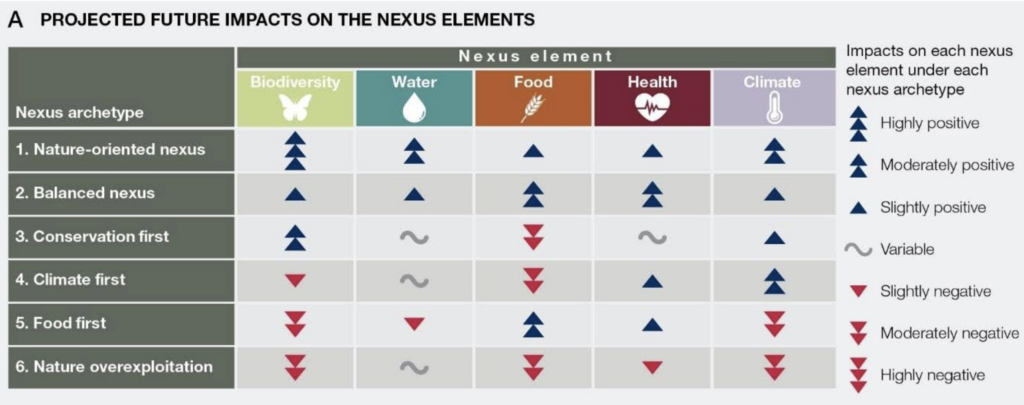

The authors used 186 outcomes from 52 studies to assess how the elements would interact with each other this century, using the data to develop six nexus scenario archetypes. They found that a focus on trying to maximise the outcomes for only one part of the nexus in isolation will likely result in negative outcomes for the other nexus element.

The first two archetypes – labelled “sustainability scenarios” – concern nature-oriented and balanced nexuses. They focus on strong environmental regulation, effective protection of natural areas, sustainable agriculture, healthy diets and food waste reduction, resulting in positive impacts for all five elements.

Meanwhile, the conservation-first archetype has positive outcomes for biodiversity and climate, but negatively impacts the food nexus. The next archetype, climate-first, results in negative impacts for both biodiversity and food.

Business as usual will lead to ‘extremely poor’ outcomes

The final two archetypes – food-first and nature overexploitation – are described as “business-as-usual” scenarios, and have negative impacts on almost all elements. The food-first archetype focuses on unsustainable agriculture and positively affects nutritional health, but this arises from an “unsustainable intensification of production and increased per capita consumption”.

These business-as-usual archetypes are characterised by intensive material, energy and land use, greater greenhouse gas emissions, and unsustainable exploitation. This is a key message of the IPBES report: if things continue the way they are the outcomes will be “extremely poor” for biodiversity, water quality and human health, with worsening climate change and growing challenges to meet policy goals.

“The future scenarios with the widest nexus benefits are those with actions that focus on sustainable production and consumption in combination with conserving and restoring ecosystems, reducing pollution, and mitigating and adapting to climate change,” said Harrison.

The link between human health and the multiple crises is startling. Nearly six in 10 human infection diseases are likely to worsen during climate change, while 16% of all deaths in 2019 were caused by increased air and water pollution (numbering nine million).

It’s why the IPBES has come up with its response options, which can allow us to manage these crises and often at low costs. They’re divided into 10 broad categories, covering pollution, sustainable consumption, ecosystem management, planning and governance, and finance, among others.

These solutions include managing biodiversity to reduce animal-borne diseases in humans, improving integrated landscape management, supporting Indigenous food systems, and reducing pesticide and plastic pollution, as well as repurposing public investments.

IPBES advises replacing meat with novel foods and sustainable healthy diets

Today, 42% of the world’s population is unable to afford healthy diets, a figure that rises to 86% for low-income countries. Over a tenth of the world is affected by food insecurity in Asia and Africa, while in 2017, 11 million adult deaths were caused by unhealthy diets.

With the global food system accounting for 21-37% of all emissions, sustainable production and consumption are key to achieving goals across the five nexus elements. The response options therefore include a reduction in food loss and waste, a shift to planet-friendly, healthy diets, and a decrease in the overconsumption of meat.

The latter involves cutting back on red and processed meat in support of “sustainable healthy diets”, which the IPBES defines as those that promote individual health, have a low climate impact, and are accessible, equitable, affordable, and culturally affordable.

“Scenarios show that sustainable healthy diets and the reduction of food loss and waste decrease greenhouse gas emissions as well as benefiting other nexus elements; in addition, sustainable healthy diets also reduce human deaths,” the Nexus Assessment says.

Shifting to such eating patterns and reducing the amount of food that ends up in the bin will benefit food security and health, reduce emissions, and free up land, providing “co-benefits for nexus elements such as biodiversity conservation and carbon sinks”.

Additionally, among the food system transformations analysed in the nature-oriented archetype is the adoption of novel food sources like macroalgae and microbial protein. “Such transformations would enable the current agricultural land area to meet the calorific and nutritional needs of future generations in the medium to long term (e.g., through improved productivity), enabling positive outcomes for human health and for biodiversity as well as sustainability.”

The report further says it’s well-established that “the way food is produced, what foods are produced and consumed, where they are produced, and how much food is lost and wasted impact both nature and people”.

“Our current governance structures and approaches are not responsive enough to meet the interconnected challenges that result from the accelerated speed and scale of environmental change and rising inequalities,” said McElwee. “This can be addressed by moving towards ‘nexus governance approaches’: more integrated, inclusive, equitable, coordinated and adaptive approaches.”