Australia & UK Lead Climate Arrests As Governments Use Anti-Terror Laws to Curb Protests

5 Mins Read

Crackdowns on climate activists have increased alarmingly over the last decade, with Australia and the UK arresting protestors three times more than the global average.

As climate protests become more frequent amid a lack of action by world leaders, a new report reveals that instead of working with these activists, policymakers are actively taking measures and creating laws to clamp down on their efforts.

Arrests, disappearances and murders are all part of an increasingly worrying trend for dissent over climate change and the environment. Since 2012, over 2,100 environmental defenders have been killed, while police violence and arrests have also become common occurrences. Meanwhile, legislations meant for organised crime and terrorism are being used against these activists.

Reviewing data from Global Witness and Armed Conflict Location and Event Data, researchers at the University of Bristol found that 6.3% of climate and environmental protests end up in arrest globally, with the number jumping by around threefold in Australia (20%) and the UK (17%). Norway, where arrests are a result of 15% of protests, isn’t far behind.

The 14-country report suggests that since 2019, there have been 22 new pieces of legislation aimed at limiting people’s ability to protest, which often “undermine existing human and civil rights legislation and conventions, including the Aarhus Convention”.

“This is worrying because it focuses state policy on punishing dissent against inaction on climate and environmental change instead of taking adequate action on these issues,” said lead author Oscar Berglund, a senior public and social policy lecturer at the university. “It also represents authoritarian moves that are inconsistent with the ideals of vibrant civil societies in liberal democracies.”

The difference between climate and environmental protest

Bergland and his colleagues focused specifically on countries with more than 1,000 protest events between 2012 and 2023, before homing in on 14 nations that represent all continents (except Antarctica).

They went on to make a distinction between environmental and climate protests. The former are described as demonstrations that specifically target destructive projects like fossil fuel extraction, deforestation mining, dams or large construction, while the latter are a newer phenomenon that are more urban in their geography and tend to have greater political demands.

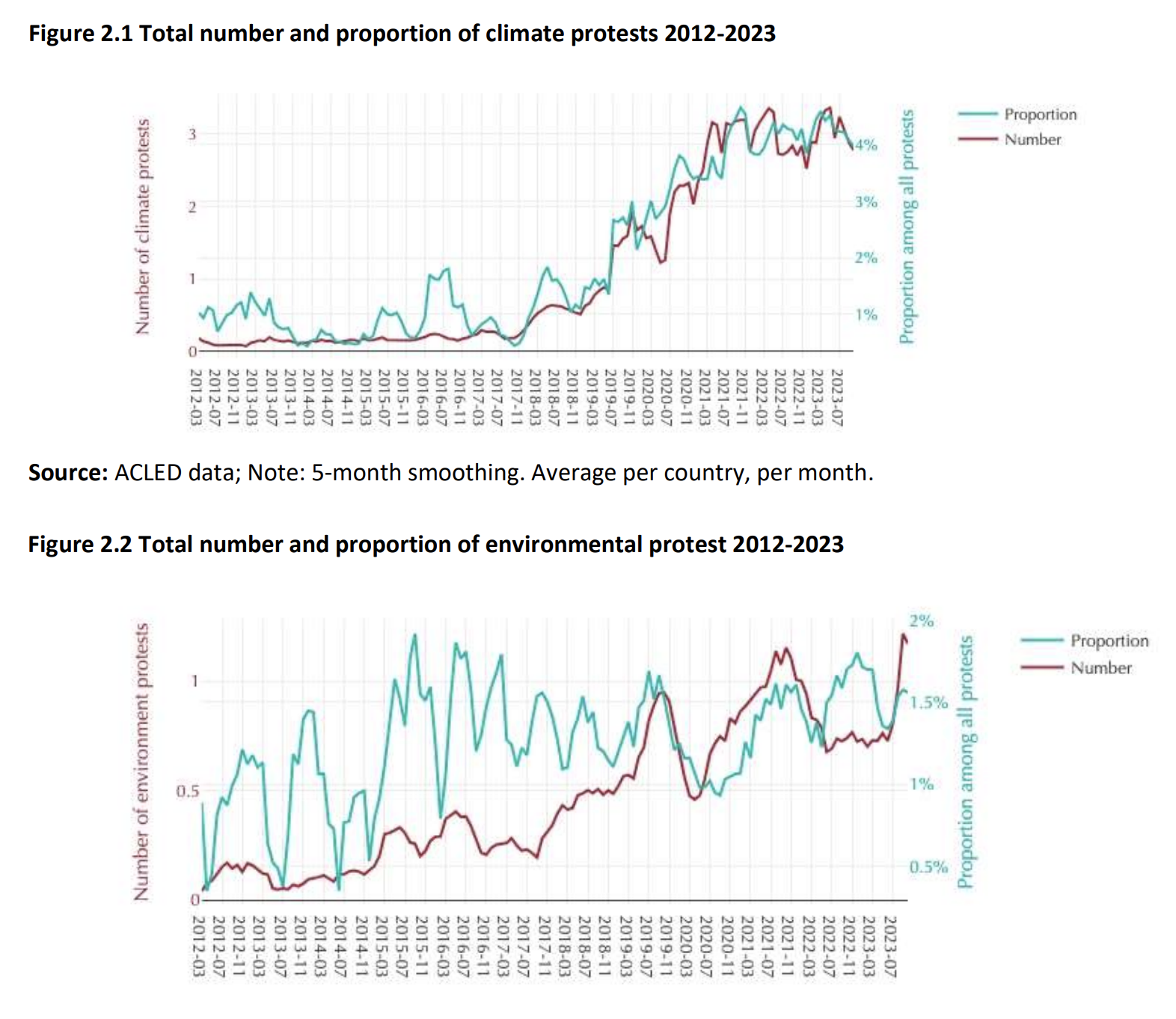

Both kinds of protests have increased in number, with environmental dissent up by about 2%, and climate demonstrations rising by 4%, thanks to a sharp uptick during the tail-end of the 2010s. This period also coincided with the largest climate protest in history in September 2019, spearheaded by Greta Thunberg.

The research found that 6.5% of protests end up in police violence in Peru, the highest of any nation on the list. This is followed by Uganda (4.4%) and South Africa (3.5%).

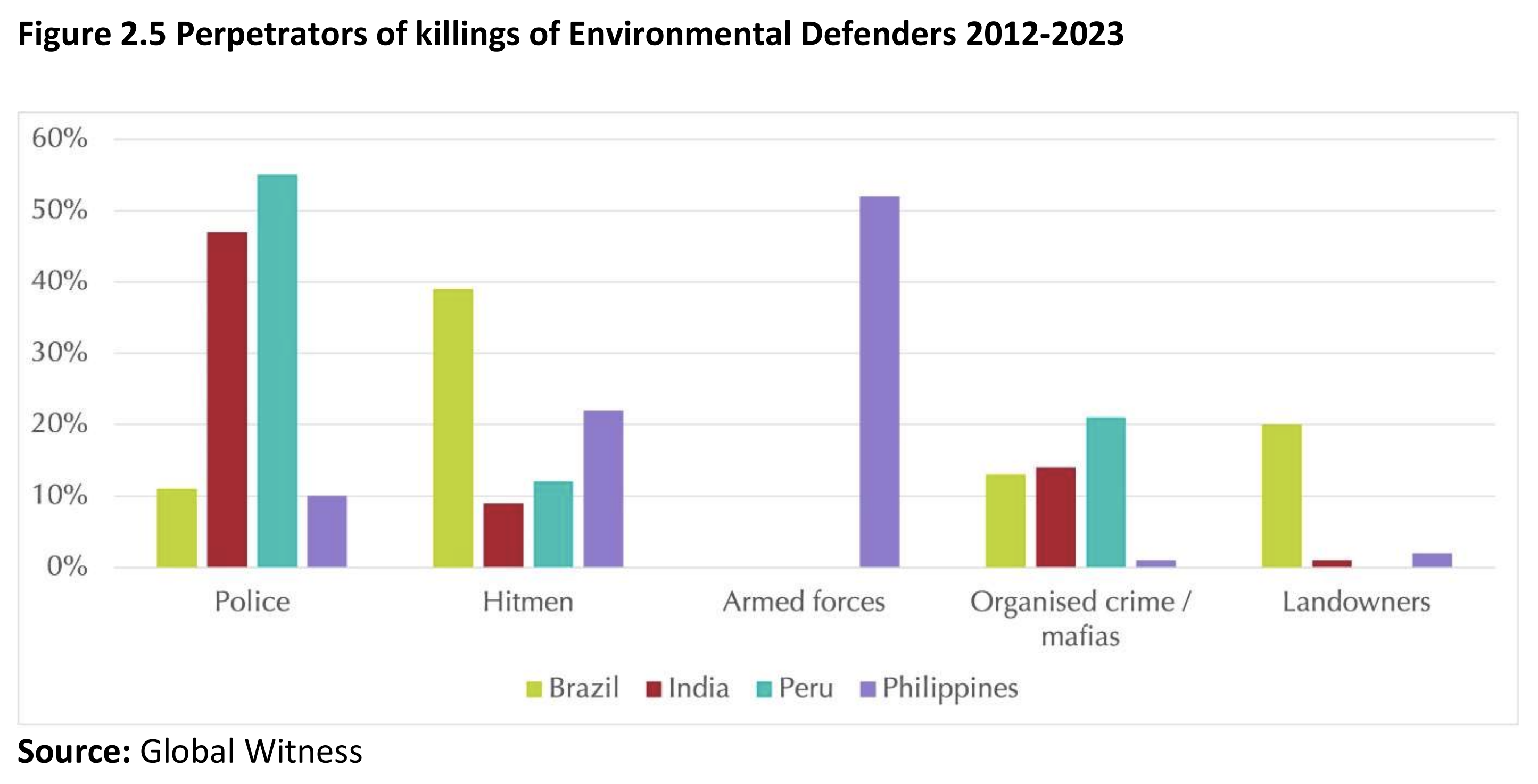

But despite having the lowest number of arrests (0.6%), Brazil has been home to over 400 killings, a fifth of the total in this period. The most high-profile of these was the murder of British journalist Dom Phillips and Brazilian Indigenous expert Bruno Pereira, who were shot for their effort to highlight deforestation in the Amazon and its terrifying impact on local communities.

The Philippines (298) was next after Brazil in terms of activist murders, with India (86) and Peru (58) the only others with double-digit killings.

Extinction Rebellion, Just Stop Oil, and Greenpeace were found to be the most common protest organisations. But even non-violent protestors have been sentenced to lengthy prison terms “designed to act as a deterrence to future activists”, like the five British Just Stop Oil activists who were handed down four- or five-year sentences in July.

Lawmakers use several mechanisms to curb dissent

The researchers highlighted four broad mechanisms used to suppress climate and environmental protestors. The first involves anti-protest laws, which introduce new crimes, make punishments more severe for existing ones, increase the power of police, and give officers impunity when harming activists.

Protests are also being criminalised through prosecution, with courts using existing legislation for the new purpose of curbing climate dissent. This can involve probing mentions of climate change in court proceedings, or changing processes to decrease the possibility of activists being found not guilty, according to the researchers.

The third mechanism concerns policing, carried out by both state and non-state actors (like private security or organised crime). Stop and search, physical violence, infiltration of movements, and threats and intimidation, all intending to stop protests from happening, are common here.

Finally, killings and disappearances appear to be common in some nations. “In many ways, these are an extension of policing as they are either carried out or permitted by the same authorities, often following death threats and other forms of intimidation,” explained Burgland.

He and his co-authors outline the need for governments and courts to operate with a presumption against criminalising environmental protest and implement “mechanisms of deliberative democracy” to generate legal definitions of terms like ‘serious disruption’.

The use of anti-terror legislation against climate activists must stop, as should the killing of environmental defenders. And extractivism projects should be governed with a participatory approach involving local stakeholders and bodies that weigh their climate risks. “Human rights frameworks should be at the forefront of policing considerations and operations to ensure that the public can exercise their right to protest without impediment or fear,” added Burgland.