Paella with Quinoa? This Future Seed Project Aims to Inspire Climate Action & Preserve Native Foods

7 Mins Read

A new project is using climate analogue mapping to send native seeds to regions that will have similar environments decades down the line.

What do the dishes of the future look like? Will we be eating the same traditional dishes in 60 years that we do now? What if we could take heritage crops from one part of the world and grow them elsewhere to address food insecurity and the changing climate?

These are questions Prof Jonathon Keats is contending with. The conceptual artist and University of Arizona researcher is working on a project to preserve locally and culturally important seeds for the future.

But it’s not your typical seed banking project. Keats is exploring how native seeds that grow in one part of the world today – but are threatened by climate change – can thrive in another area that will have a similar climate decades from now.

The idea is based on climate analogue mapping, a model devised by fellow researchers from the University of Maryland and North Carolina State University. Essentially, it determines where you’ll find the climate today that your current place of residence will experience in the future – whether that’s 10 or 20 years, or even a century or more.

The predictions are based on UN models and were created to understand the changes in flora and fauna as a result of the climate crisis. Keats was interested in the cultural aspect of this methodology, using it to identify the ideal future regions for foods that are traditional to you.

His project, called Seeding Tomorrow, involves sending local seeds in jars to climate analogue regions and burying them in a public space, as well as distributing seed packets to families. They’re meant as agricultural insurance – but also as an incentive to take a stand against climate change. If those seeds stay buried or unused, that’s a win for the planet.

“Agriculture moves very slowly. And farmers need to know that there will be a demand for crops, well in advance of making the commitment to changing crops,” says Keats, who is also working on an atlas of traditional ecological knowledge to help people make long-term decisions.

“So this is a way to be able to transfer that knowledge to prepare people, and to also create the systemic level of experimentation and have the confidence to make the changes that are going to most likely be needed,” he explains.

Born out of a heritage cuisine project

Seeding Tomorrow is a sister project of a heritage cuisine initiative called Tasting Tomorrow. Keats is based at the University of Arizona’s Desert Laboratory in Tucson, whose climate analogue is Burgos, a city in Spain.

He worked with James Beard Award-winning chef Janos Wilder (also based in Tucson) to reimagine olla podrida, a traditional dish from Burgos. “How do we sustain your cultural heritage – and specifically your culinary heritage – but in a way that is sustainable in terms of the ingredients and demands [of] irrigation, energy, input, and all the other factors,” Keats explains the thinking behind the project.

The Spanish red bean is a key ingredient in olla podrida. To substitute it, Wilder used the tepary bean, grown by the Tohono O’odham people in the Sonoran desert since time immemorial and is highly drought-adapted to Tucson. Similarly, instead of the rice used as a binder for the blood sausage in the stew, he utilised Sonoran white wheatberries as an alternative.

The project helps to offer a vision for what olla podrida could look like in 50 years’ time, when Burgos’s climate resembles the hot, dry climate of Tucson today.

Other examples of climate-analogue locations include San Francisco and Tangier in Morocco, Mexico City and the Sanaa region of Yemen, as well as Hong Kong and the northwest Indian city of Alipurduar.

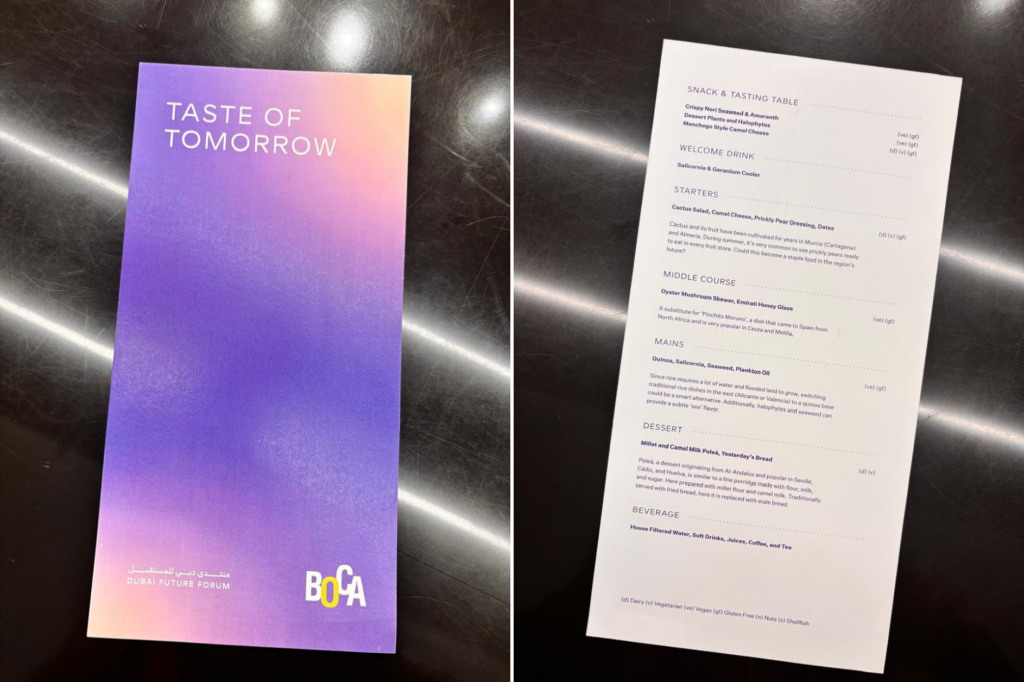

Another such link exists between Seville, Spain and Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, which Keats demonstrated at a Taste of Tomorrow dinner at the Dubai Future Forum last month, in partnership with BOCA restaurant. The idea was to highlight how many places in the Gulf have the future climate of regions in southern Spain.

Green Queen founding editor Sonalie Figueiras was present at the event, and tried dishes like a paella made from quinoa and seaweed and oyster mushroom kebabs (instead of the pork-based pinchos morunos). “The use of quinoa was proposed by the restaurant, and fits their interest in sustainable ingredients that can be grown in local climate conditions. That said, it has not been traditionally grown in the Gulf,” says Keats.

These efforts point to a mounting and crucial problem. A tenth of the world’s population has been facing chronic hunger thanks to a combination of Covid-19, geopolitical conflicts, and climate change. If the latter isn’t addressed, the risk of hunger and malnutrition could rise by 20% by 2050.

And about 80% of the people at risk from climate-change-induced crop failures and hunger live in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia, highlighting why these are among the regions most vulnerable to the climate crisis.

How Seeding Tomorrow works

Keats’s project has two aspects to it, one more public than the other. In an installation funded by Germany’s Goethe Institute, Seeding Tomorrow developed a prototype of seed packets for San Francisco.

“It’s a matter of putting the seeds in people’s hands so that they have these packets with seeds for plants that are typical in an analogue location. And the packet challenges you to keep it sealed,” he says. In the San Francisco initiative, the team took tangerine seeds – which is where Tangier gets its name from – and delivered them to locals on the West Coast.

The seed jars are a little more complicated, as they require large-scale cooperation between people from different locations. “What we want to do is to find a community in West Bengal willing to identify food crops that are really traditional in terms of being well-adapted to the climate there, and to write instructions in the local language for growing those seeds and cooking those food crops,” says Keats.

These will then be sent to people in Hong Kong, who will make a seed jar – ideally in Cantonese and with traditional materials – which will be annotated with information about the viable substitutions to those crops.

“All of this will be buried in the ground and marked with a brass marker in a public place – a botanical garden, for instance – where essentially it’s a time capsule, but a time capsule that is meant never to be disinterred,” he explains.

“The idea is that it gets buried and people see and recognise it simultaneously as a sort of insurance that is best not cashed in because ideally, we make conditions on Earth better.”

The importance and challenges of global seed banks

Currently, the Seeding Tomorrow project is without any funding, operating in good faith and with in-kind support from originations including the Metropolitan Autonomous University in Mexico City and the Highland Institute in Nagaland, India.

That is in stark contrast to the well-established seed banks across the globe, such as the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, the Millennium Seed Bank, the Indian Seed Vault, and the US National Center for Genetic Resources Preservation.

Keats believes these large seed banks are “really important”. Monocropping, for example, has led to a loss of biodiversity that’s essential for dealing with climate change impacts. “So for the place that deposited the seeds, they’re really important to have,” he says.

They also serve as an inspiring symbol for the world, in that there’s a commitment that implores people to think longer-term and act in the present to safeguard the future.

But these seed vaults have several challenges, chief among them being the transportation of seeds. Keats says they haven’t worked this out because they have a lot of other things to focus on, primarily food sovereignty: “And food sovereignty is really important in its own right, but it is not necessarily viable in the sense of seeds remaining where they are.”

He continues: The conditions of climate change result in a sort of a three-body problem: the land, the climate and the people are all changing in their relationship with each other. And so we’re going to need to respect food sovereignty, but [also] to think beyond that in terms of the complexity of the problem. And thus far, the seed banks are not doing that.”

Seeding Tomorrow, he argues, is simultaneously working with people on both climate mitigation and adaptation. “The last thing we want is for people to be paralysed by the cataclysmic conditions that potentially obtain with climate change,” says Keats. “That will only make matters worse.”

“I think it’s really important to recognise that there still are possibilities. It won’t be the same, but nevertheless, there is the possibility that you will still be able to have your traditions. And those traditions are all that much more important because of the many different ways in which the world will change.”