From the Impossible Burger to A Carbon Ranch, Film Spotlights Pat Brown’s Bid to Save the Planet

5 Mins Read

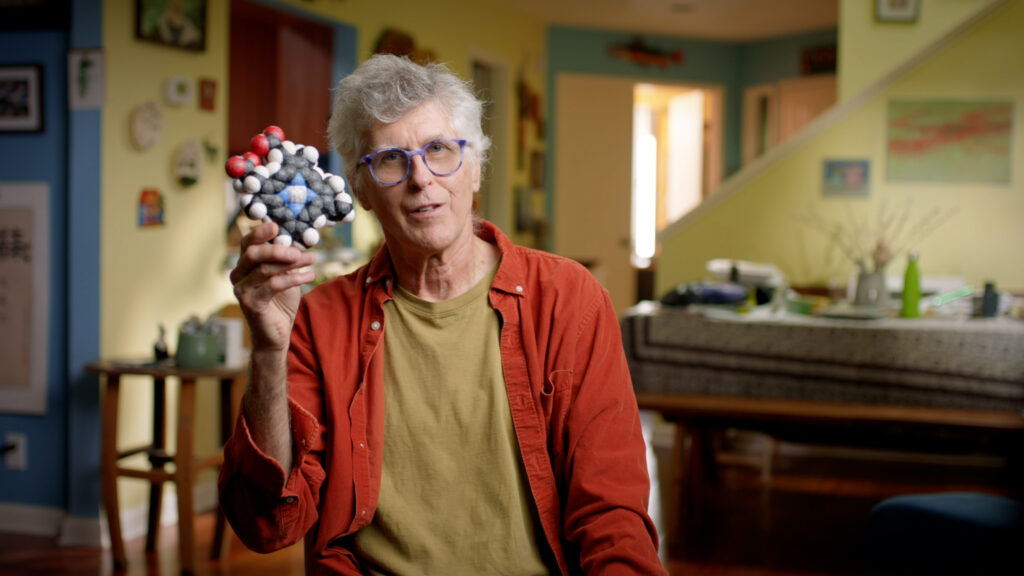

Impossible Foods founder Pat Brown is the subject of a recent episode of the Wild Hope documentary, which details his dedication to fighting climate change, and his new Carbon Ranch.

After decades spent in labs, Pat Brown is taking to the field.

The founder and former CEO of Impossible Foods, one of the most seminal companies in the alternative protein ecosystem, is leveraging his experience in academic and corporate America to tackle the biggest issues in the heartland.

On a 1,000-acre Carbon Ranch in Arkansas owned by the Poland-based Impossible Foundation, Brown and fellow scientist Michael Eisen are creating a model to show farmers how carbon-intensive cattle ranches can be transformed into carbon-capturing forests.

Brown’s journey from biochemist to food CEO to land restorer was detailed in a recent episode of the Wild Hope docuseries, titled Mission Impossible.

Problem one: cattle farming

The work on the Carbon Ranch is built on research by the two colleagues in 2022, which suggested that a phaseout of animal agriculture over the next 15 years would have the same effect as reducing emissions by 68% through the rest of the century.

The study was published in PLOS Climate, a journal owned by the Public Library of Science, an open-access publisher co-founded by Brown at the turn of the century. Since then, he took a sabbatical that led to the establishment of Impossible Foods.

“What I wanted to do on the sabbatical was to figure out what was the most important thing I could do to make the best possible world,” Brown says in the documentary. “The environmental impact of the animal ag industry was completely unacceptable, and no one was seriously trying to make it go away completely. So that’s what I decided I was going to do.”

Figuring out what makes meat taste the way it does, and finding the necessary components to deliver an animal-free alternative, was “the most important scientific challenge in the world”, he says.

The documentary details Brown and his team’s bet on heme, the iron-rich red molecule that is said to give animal products the meaty colour and flavour they’re known for. Brown recalled that heme is also carried in soy leghemoglobin, a protein present in high concentrations in soy root nodules.

To produce it at scale though, the team turned to precision fermentation, inserting the DNA from the soy plants into a genetically engineered yeast strain called K. phaffii, which is then fermented in a similar way to how Belgian beer is made. The soy leghemoglobin is then extracted from the yeast and added to the plant-based ingredients that make up the Impossible Burger.

It formed the base of Impossible Foods’ success, which soon partnered with Burger King to launch the first vegan Whopper, in a distribution deal that still runs today.

Beef is the most polluting food on the planet, and as a whole, livestock farming emits a fifth of the world’s emissions. According to the Californian firm, the Impossible Burger generates 89% fewer greenhouse gas emissions, consumes 87% less water, and uses 96% less land than conventional beef.

But 11 years after establishing the company, Brown turned to the next stage of his quest to safeguard the planet and undo the harms of the animal agriculture economy.

Problem two: land restoration

“If you get rid of the demand for meat products, you have two problems you need to solve,” Brown told Wild Hope in an interview. “Number one, what happens to the people who make their living raising animals for food? Obviously they’re not the bad guys. They’re just trying to make a living, doing an incredibly hard, dangerous job. So, what happens to them?

“Secondly, you don’t realise the benefit of eliminating the use of land for animal agriculture unless you use that land to restore the native ecosystems and recover carbon from the atmosphere.”

This is why Brown stepped down from his role as CEO in 2022 to focus on specific strategic initiatives at the company, including hands-on research, public outreach and technology progress.

The Carbon Ranch he’s working on now had 800 cows when it was first bought, who were moved to a nearby land by the previous owner. “We’re so used to thinking of a cattle farm as… a part of nature,” Brown says in the documentary. “And it’s the destruction of nature.”

Brown and his colleagues cleared the land to give it the opportunity to recover, and divided it into three sections. In the first, they did no intervention. In the second, they planted a mixture of 30 different native tree species, and in the third, they cultivated 330,000 fast-grown timber species.

“The product we want from this experiment is a playbook for farmers and ranchers that basically tells them how to do this, and how to make a living by doing this,” he said in the interview with Wild Hope. “Because they’re ultimately going to be the ones that are carrying out the transformation, and we want them to be able to make a really good living from it.

“The best way for that to happen right now is through carbon markets. Because if you’re capturing carbon through reforestation, you can get paid a decent amount of money. And if it works well, a lot of farmers are going to opt to do that, so we need to figure out how well that works.”