Meatable CEO Jeff Tripician: ‘I’d Be Disappointed If We Don’t Have Approval in 5 Countries Next Year’

14 Mins Read

Meatable’s Jeff Tripician gets practical. In an exclusive interview, he tells Green Queen about his journey from meat industry veteran to cultivated meat CEO, why these proteins should be more expensive, the company’s upcoming Series C round, and its global regulatory plans.

“It’s just a very practical conversation,” says Jeff Tripician. The current demand for eight billion people is taxing the food system. You have rising emissions, alarming rates of soil degradation, a huge amount of freshwater used to feed and grow animals that we eat.

“What do you do 25 years from now, when [the demand for meat] is 70% bigger, there are two billion more people, and developing countries [are] eating more?” he asks. “Hell, that’s why I joined this.”

The ‘this’ Tripician is referring to is Meatable, the Dutch startup making cultivated meat. He joined as CEO in May, taking over from co-founder Krijn de Nood, who remains on the board. His appointment hints at the company’s US expansion plans, leveraging his decades-long experience as a meat industry executive.

“I was part of the meat industry. I’ve run these companies, and I don’t have an answer to that question,” Tripician, who has worked at Perdue Farms and Grass Fed Foods, tells me. “I don’t know if cultivated meat is the perfect answer, [but] I know that it has huge positives.”

Cultivated meat can do in 12 days what it takes a pig eight months to, and a cow two to three years. The technology involves minimal waste, a fraction of the land and water use, and a dramatic reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. “It does a lot of things, and it does it at once, at scale, and at a price that’s reasonable,” suggests Tripician.

“In our case, the taste is so close to conventional pork that if you use it as an ingredient, like a sausage, or in a taco, burrito, or meatball, you cannot tell the difference. Because it’s real meat. It comes from real pig cells.

“So you sit there and think: ‘If this isn’t the answer, I would like to know what is.’ And you hear nothing. The meat industry goes: ‘Well, we’ve already invested in all of this, so we’ll just continue to push.’ If they’re successful, they will further stress the planet. If they’re unsuccessful, they don’t have enough meat to feed the planet. Which is worse?”

Cultivated meat appeals to tech-savvy Gen Z

That being said, Tripician says the company has had a “big change” in approach: “The role of Meatable is to help meat companies gain access to more meat. We’re a supplier to them. We show them the technology. We transfer the technology so they can do what they do. They take raw material – meat – they turn it into food, and they sell it. We now provide them with some of the meat. Very simple.”

Meatable conducted a survey of 500 chefs in the US, 60% of whom said they’d put its cultivated pork on the menu, alongside the message and the brand name. It then polled thousands of consumers – while older ones were more apprehensive, younger Americans were excited.

In Tripician’s mind, there are two ways meat companies (this includes plant-based) can cater to the growing protein demand. The first involves combining a plant-based product – which “just doesn’t taste as good” – with a percentage of cultivated cells. This hybrid route is what’s currently being taken by most cultivated meat startups right now.

The problem here is that “there’s a younger consumer that says food is supposed to do more than provide calories and nutrition”. Indeed, taste is the most important purchase driver for nearly three-quarters of Gen Zers in the US.

That’s where the second approach comes in. “You take your conventional product, add in some Meatable, and now some of that is helping make it a better place. I think that’s a route that would work, and it’s cost-effective at that size.”

He points out that younger Americans are holding sustainability dearer than perhaps older generations do. Their purchasing power is massive, and they’re not afraid to switch to a different brand if it doesn’t meet their ethical needs.

“So if the meat industry wants to help itself, they should say: ‘I’ll put some of those things on the shelf with my name on it, not Meatable’s name, and have those consumers go: ‘Great!’” says Tripician.

“We saw it with plant-based,” he adds. “People tried it, didn’t really buy it again, it fell off dramatically. That’s simply fixed with taste. Change the taste, change the texture. We tested a 25-30% [cultivated pork] blend. For an average person, you could not tell the difference between that and a 100% pork product.”

‘I won’t tell billion-dollar meat companies what to do’

Meatable has been using similar rations for its tastings. The company held two events in Singapore last year, and one at its Leiden headquarters in the Netherlands in April – this was the first on EU soil.

“We try host investors and government agencies and so on, just give them a chance [to try], because they can’t go buy it yet. Really, Singapore is the only place that’s embraced cultivated meat – we do regular tastings there,” says Tripician.

“It brings the media into the discussion, and other parties that can influence positive outcomes. [The tastings] were really well received. We continue to do them in other places, with other people… What we’re talking about at the end of it is: this is food, how do you feel about it?”

Meatable will host a large tasting event in February 2025 with investors, the company’s board and meat companies interested in how to feed 10 billion people by 2050 with fewer resources at hand.

As for how much cultivated meat clients want to add to their product, Meatable leaves it up to them. The startup can show them different recipes, whether that’s a mix with pea or soy protein, or even a vegetable patty with butternut squash, carrots and mushrooms. “You can blend other things in here that have high nutritional value, no sugar added, all kinds of health benefits.”

“It’s really up to the business, meat company, grocery store, restaurant,” says Tripician. “So if you’re a meat company – Impossible, Cargill, JBS, whoever it is – and you go: ‘You run plants, you bring in livestock, you harvest, you fabricate, you turn it into food, put it in cold storage, put on a truck, you sell to restaurants and grocery stores.’

“All we’re going to do is say: ‘We’ll give you the technology, so you can have the equipment in your plant to make cultivated meat.’”

Tripician doesn’t want to change what meat producers do. “I’m not going to tell a $15B company how to make their product. I’m going to say: ‘I can get you raw material at a competitive price in 12 days, guaranteed, regardless of whether, regardless of feed prices, regardless of pandemics or diseases like avian or swine flu, regardless of all of that hailstorm, none of that matters.”

He continues: “When they go to their customers, they would be able to say: ‘Look, you seem like a progressive chef. You’ve got the younger people, they’re all on their iPhones… Do you think a product like this would make sense?’”

Meatable looks to collaborate with fellow cultivated meat producers

One of the defining features of Meatable’s business is its production process, which was recently updated to halve the manufacturing time to just four days. This is made by its Opti-ox technology, which allows it to make products by isolating a single animal cell, without the need for fetal bovine serum.

The process uses pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), which – unlike immortalised cell lines that need to be altered to multiply indefinitely – have the natural ability to continue multiplying, and do so rapidly. This is coupled with a perfusion process that allows the startup to work in a continuous cycle to generate very high cell densities and produce fully differentiated muscle and fat cells faster than any competitor.

The company moved to its Leiden facility in November 2023, which houses 200-litre bioreactors (with the potential of expanding to 500 litres). It has also partnered with Singapore’s ESCO Aster, the world’s first approved contract manufacturing facility for cultivated meat, and plant protein manufacturer Love Handle.

But scaling up to meat industry levels is an immense challenge that has troubled even the most well-capitalised companies in the space. Tripician, for his part, doesn’t want to own a pilot plant. “We’re going to go to people that are our colleagues, and we’re going to say to them: ‘You figured this out. Why don’t we work together?’” he says.

Meatable is reaching out to cultivated meat pioneers in Australia, Europe, the UK and elsewhere to collaborate. “I want to use their pilot plant. I want to use the things they know, so that when we figure it out, we obviously benefit. And so do they. There’s more than enough demand for a bunch of us to be successful.

“Because – this isn’t going to shock anybody – what happens if, five years from now, the technology changes and the equipment’s different, you have to redo all the equipment. I don’t own any equipment. I don’t want to own any equipment.”

Cultivated meat ‘should not be at price parity’

One key advantage of scaling up is that it will bring costs down, which is critical if cultivated meat is to reach the masses one day. The sector has managed to lower costs by 99% in the last decade, but a report from McKinsey suggests it will take at least until 2030 for these proteins to reach price parity with meat.

Tripician, however, doesn’t believe cultivated meat should cost the same as its industrially farmed counterpart. “I think it should be a little bit of a premium,” he says. “As an industry steward, if it gets to parity, then farmers and ranchers are at risk, because it would be the same price, and I want them to be a little bit lower, so that their businesses are always strong.”

He adds: “And if you’re going to ask a meat company to invest hundreds of millions of dollars in plants and facilities, they better make a little bit more money.”

But where does that leave the consumer? Tripician points out that between 6-23% of the dairy, produce, egg and bakery industries are made of premium-priced items. “These are 100-billion-dollar industries just in the US. If those can be that penetrated, then you would think the same premium on meat would be equally effective.”

He puts it in the same bracket as organic meat, which can be 70-75% higher than commodity meat. “It’s more, but it’s an amount people pay for,” he feels, forecasting such prices for cultivated meat in the next two to three years. “After that, it will come down more, a slow glide down.”

Targeting a Series C raise in the $30M ballpark

To date, Meatable has raised $95M from investors, and that’s excluding grants like the €7.6M pumped in by the Netherlands Enterprise Agency under its Innovation Credit programme last month. The company is now working on a “modest” Series C raise, which would close at around the $35M mark (similar to its Series B round last year).

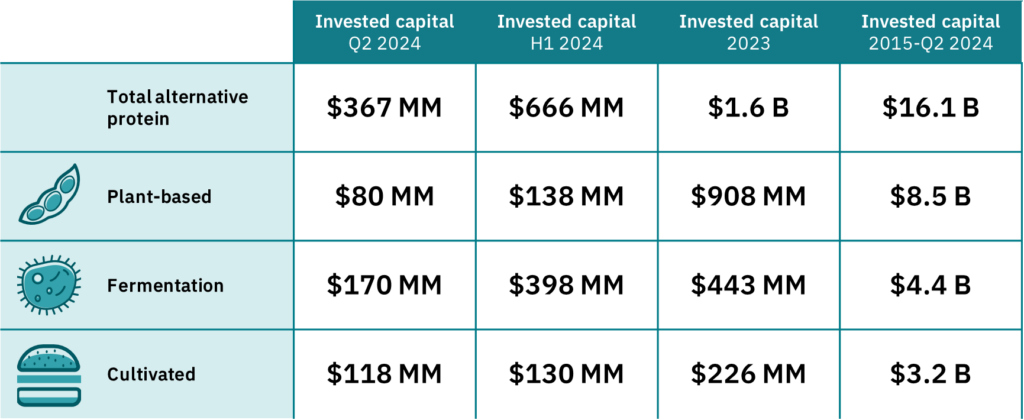

It’s part of the startup’s asset-light approach – it’s not building a plant, and it’s not competing with the rest of the industry in terms of production, distribution, sales, and the like. Lately, investors have cooled on cultivated meat – as they have on the wider food tech sector – though the downward spiral may be ending.

“They hate the asset-heavy thing,” Tripician says of venture capitalists. “They’ve lost a lot of money, or think they’re going to lose a lot of money in that. Because it’ll be very, very difficult for a pilot plant in cultivated meat to ever make money… We’re not pursuing that.

Meatable has an 18-month runway, which is on the healthy side compared to many in the industry, though the Series C would buy the company more time. “We’re fine, but I want to have more than fine, and I think that’s smart to say to an investor,” its CEO says.

“Look, if you believe we’re on the right path and the science and the IP and all that’s there, and our business model is going to be successful, can you invest an amount that will get us through this time?” he says when asked what his pitch to investors would be. “I know the meat companies will be buying licenses from us, building plants, and entering the marketplace over the next five years.”

He reveals that the business is doing a “soft launch” for existing investors who might satisfy the capital requirements though officially the round will open in January 2025, with the aim of closing it by the end of spring.

Meatable expects regulatory approval in multiple countries next year

Each of Meatable’s seven business hubs services the countries around it. For example, its Asian base is in Singapore, the first country to approve cultivated meat, and one that is currently evaluating Meatable’s application too.

“We’ve got meat companies there that know there’s regulatory approval, or there will be, within 12 to 18 months,” says Tripician. “That’s where it’s going to gain traction, and then we’ll follow.”

He adds: “I flew out and sat with the Singapore Food Agency. Their thinking – this is an American saying this – far exceeds ours as far as coordination between ministries of government, the Economic Development Board… and the private industry [goes]… Now, they also have a different background. We are not food insecure – they are. The US doesn’t have that pressure, and [Singapore] is a small country, but the coordination was truly impressive.

“They’re helping with staff. They’re helping open doors, and that’s the model. If countries go: ‘Our water is a problem, our soil is a problem’ – maybe it’s not food insecurity, you have other issues – then you should be facilitating solutions, not rejecting.”

Tripician says that Meatable is currently filing dossiers in six countries. “The Singapore regulatory approval process is largely welcomed. Several other countries out in Asia look to Singapore and say: ‘Well, we pretty much follow that.’ It’s not 100%, it’s not guaranteed, but it’s very alike,” he says.

“So we’re perfecting it with Singapore, and then we’re just taking it and saying to the other countries: ‘Here’s what we have. What do you need to see that’s a little different?’” he adds. “Some of them are saying nothing. Others are going: ‘Well, we could use a little more data here or a little more information there,’ and we go: ‘Absolutely.’”

Once the Singapore approval comes through – which Tripician expects by Q1 2025 (“we’re just a little short on the explanation, not the science”) – Meatable will use that to get authorisation in a host of other countries. The UK’s Food Standards Agency has announced its intention to use a framework for international cooperation for novel food approvals too, a partnership likely to include Singapore.

“I see us moving with pretty good speed through 2025,” predicts Tripician. “At the end, I would be very disappointed in our team if we don’t have approval in five, six countries by this time or the end of next year.”

The EU is ‘leading with science, not a fear of change’

What about things closer to home? So far, the EU has only received one application – from France’s Gourmey – thanks to the make-up of its existing novel food regulation. The complexity and timelines have led homegrown startups (like Meatable) to look internationally for launch plans.

“Countries and areas have their own hurdles, the things they care about, and it’s up to companies to navigate that. It’s not up to [EU members] to change their mind,” says Tripician. “We’ve been working with them in a way that we’re leading with science, not the fear of change.”

He believes the EU is taking a “very methodical” approach to the regulation of cultivated meat and other novel foods, and is now questioning the barriers it previously put up.

“If the product is safe, and you have bigger problems – climate change, feeding your people, soil, use of land – do you really want to use all of that land to raise feed? Or do you want to convert it to feeding people?,” asks Tripician. “Those are internal conversations, but they’ve been very supportive.”

Cultivated meat bans ‘anger’ Meatable CEO

As for Tripician’s own home country, a wave of states have been attempting to restrict this industry – Florida and Alabama have already banned cultivated meat”, with the former currently facing a lawsuit for the decision. “As an American, it angers me,” Tripician says.

“They don’t have a better idea, but they’re going to shut this down,” he adds. State politicians are suggesting that cultivated meat could be bad for farmers and ranchers. “That’s just un-American. We’re supposed to pick what we want, as long as it’s safe, [we’re] not supposed to have someone tell us what to do.”

He wants to appeal to state governors, whom he describes as “smart people” who are “trying to do the right thing”: “I would ask them the same question we started with: if you don’t like cultivated meat for whatever reason – probably political because farmers and ranchers vote – what’s your answer for five, 10, 15, 20, 25 years from now?” he wonders.

“We already have 10% of the global population going to bed hungry every single night. What’s that number going to be? Is it going to be your kids, your grandkids, your nephews, your nieces, your neighbours? What’s your answer?”

He adds: “I think if you’re not part of the solution, my god, please don’t be part of the problem. Just get out of the way. Let the FDA and USDA do their job. They’re really good at it. If it’s a problem, they’ll stop it.”

Drawing on his experience as a “meat guy”, he believes that farmers won’t be hurt by the success of cultivated meat as an industry. “Farmers and ranchers are the best stewards of the land. Nobody cares more about the quality of the land than them and the livestock they treat with respect. They don’t want to do anything bad to them, but if they’re running out of meat, then everyone’s going to push them for more,” he says.

Cultivated meat can take some of that pressure off. The livestock farmers and producers wouldn’t be impacted negatively if cultivated meat grew at a reasonable rate – one that they decide, based on how much they want to include in their formulations.

“The meat companies then could say: ‘Now I have enough meat, I can feed the people, and that meat doesn’t destroy soil, water or air. It doesn’t do the harm,’” says Tripician. “How does that puzzle not fit together?”