Big Meat Rivals Big Oil’s Methane Output – Governments Need to Step In

5 Mins Read

Meat and dairy giants produce as much methane as the world’s largest fossil fuel companies, but non-action would result in global heating of 0.32°C by 2050.

At COP26 three years ago, leaders from around the world came together to adopt the Global Methane Pledge. Now featuring the signatures of 158 countries, the target is to reduce emissions by 30% by the end of the decade.

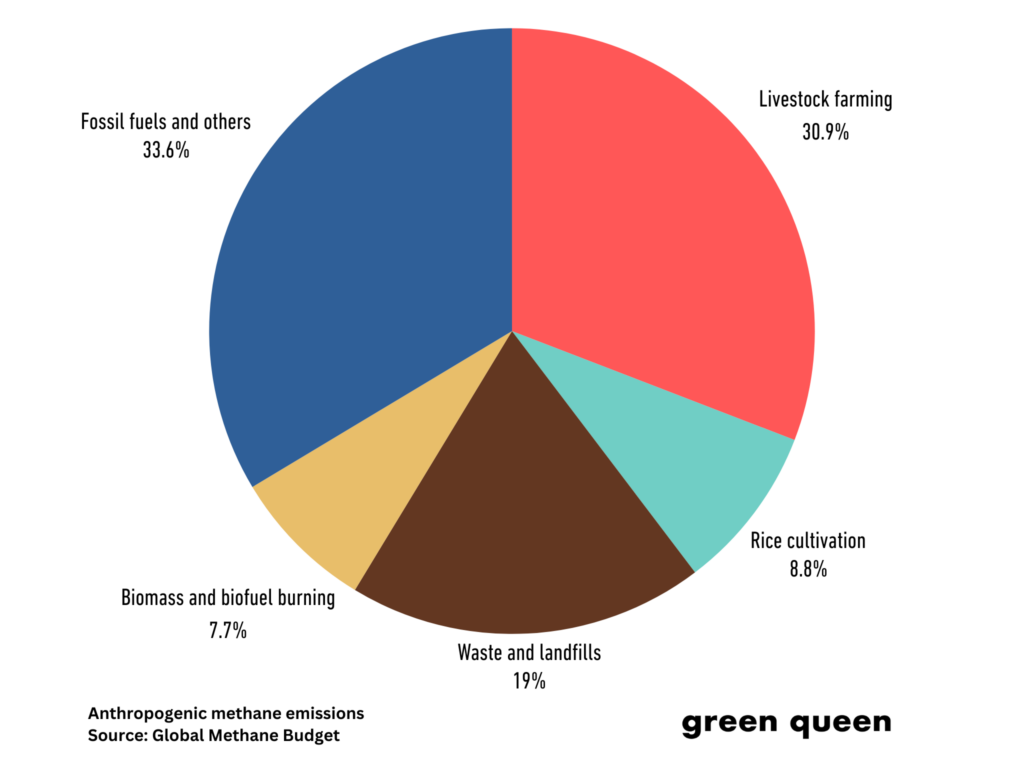

But the pledge only focuses on drastic methane reductions from the fossil fuel sector, not the agriculture industry, which is the largest source of anthropogenic methane emissions. Within this, meat and dairy production is the biggest culprit, responsible for 31% of the output.

As things stand, the road to 1.5°C is virtually a dead-end. If you ask some climate scientists, even limiting post-industrial temperature rises to 2°C is wishful thinking. Without addressing the food system, there’s no way we’re meeting our climate goals.

That is because the methane emissions from 29 major livestock producers rival those of the fossil fuel industry’s 100 biggest emitters, according to a new report by Greenpeace Nordic.

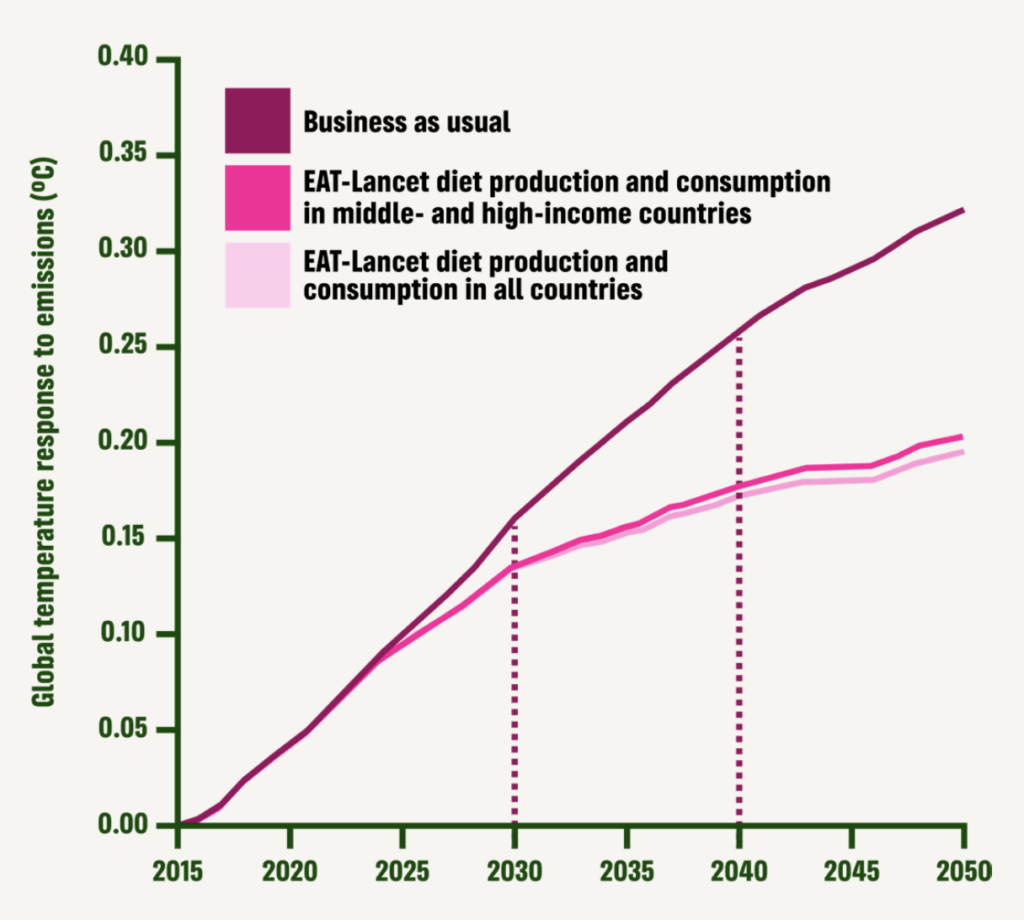

The analysis, which comes a month ahead of COP29, suggests that if we don’t take action to curb this impact, meat and dairy alone could lead to a temperature rise of 0.32°C by 2050. But if we cut our production and consumption of animal products in line with the Eat-Lancet Planetary Health Diet, we could prevent 0.12°C of warming in that period.

This would provide a ‘cooling effect’ on the projected heating levels from the livestock industry, amounting to a 37% reduction in warming by 2050 compared to a business-as-usual scenario.

“For so long, we have tiptoed around big meat and dairy companies and their unfettered growth as if they are somehow exempt from making the drastic changes required of everyone else on this planet,” said Shefali Sharma, senior agriculture campaigner for Greenpeace Nordic, calling the findings incredibly hopeful.

“It’s always either the farmer or the consumer who has to change, while these companies decide what farmers grow, what they are paid and what we eat. We have shown that the pathway is clear.”

Methane from meat and dairy is hurting the planet

The report models three projections to determine how the meat and dairy sector will affect warming between now and 2050. In the first projection, where things remain as they are, meat and dairy production would lead to 0.16°C of warming by the end of the decade, on the way to the aforementioned 0.32°C rise by 2050 – and this doesn’t include the impact of fossil fuels.

In the second projection, where middle- and high-income countries adopt the Planetary Health Diet, livestock methane emissions would actually be reduced by 0.06°C by 2030, and 0.12°C by mid-century. And in the third scenario, all countries would take to this dietary approach, leading to a cooling effect of 0.13°C by 2050.

Greenpeace Nordic calls these “hopeful projections”. “It’s a pathway that rights wrongs in the food and agriculture sector by driving out overproduction and overconsumption of meat and dairy,” explains Sharma.

The report found that the methane emissions of the five largest meat and dairy companies – JBS, Marfrig, Minerva, Cargill and Dairy Farmers of America – are higher than those of the combined emissions of ExxonMobil, Shell, Total Energies, Chevron and BP.

JBS, which has been sued for greenwashing by New York state’s attorney general, would rank fifth if put on a list alongside the world’s largest methane-emitting corporations across sectors. Its methane output alone is higher than those of ExxonMobil and Shell combined.

ExxonMobil’s methane emissions would also be surpassed by the combined emissions of the world’s three largest dairy processors, Dairy Farmers of America, France’s Lactalis and New Zealand’s Fonterra, showcasing the huge footprint of not just meat, but also milk producers.

Governments need to clamp down on greenwashing

The report suggests that meat and dairy companies effectively have no plans for a just transition pathway. For example, JBS invested in a cattle unit to triple its production capacity, and is banking on a 70% increase in demand for meat by 2050.

There are also plenty of tactics to actively avoid this transition and greenwash consumers. One major way they do this is by relying on emissions intensity over absolute emissions – the dairy industry’s emissions intensity reduced by 11% between 2005 and 2015, but its absolute emissions were up by 15% in that period. “Any reduction in emissions intensity can easily be negated by an increase in overall production of meat and dairy products,” the report says.

Moreover, the industry is promoting regenerative agriculture, which has no widely agreed definition, while exaggerating carbon sequestration potentials. Meanwhile, carbon offsets are are being used as a tool to compensate – not eliminate – their methane emissions, but there are two problems here: offsets rarely work, and if even they do, we need to increase carbon sinks while also reducing absolute emissions.

Technological fixes like biogas (which has been criticised by many experts), feed additives (a largely unproven solution), and selective breeding (which could work, but takes too long for it to make a difference now) all leave a lot to be desired.

This is why Greenpeace is calling on companies to report their full scope of supply chain emissions, cut emissions through reduced livestock numbers (without using offsets or insets, start meeting annual targets aligned to the Paris Agreement, stop expanding into natural ecosystems, and ensure ingredients are sourced from areas that aren’t ecologically sensitive or linked to human rights violations.

To keep them in check, governments are called upon to set binding regulations for meat and dairy companies to report and reduce their full-scope emissions, stop the expansion of industrial livestock and animal feed production, lay out strategies to shift public funding away from the sector, and introduce policies that encourage a shift to plant-based foods.

“Governments have to step up to the plate and drive the investments and rules that will get us on this hopeful pathway,” says Sharma, calling on policymakers to “support farmers and workers in a just transition” and give the world “a fighting chance to limit global heating while saving millions of lives and livelihoods”.