Explained: How Methane Emissions Are Linked to the Food System, and What We Can Do About It

8 Mins Read

Methane has highly detrimental impacts on the planet, with the food system – particularly livestock – the main emitter of the gas. What can we do about it?

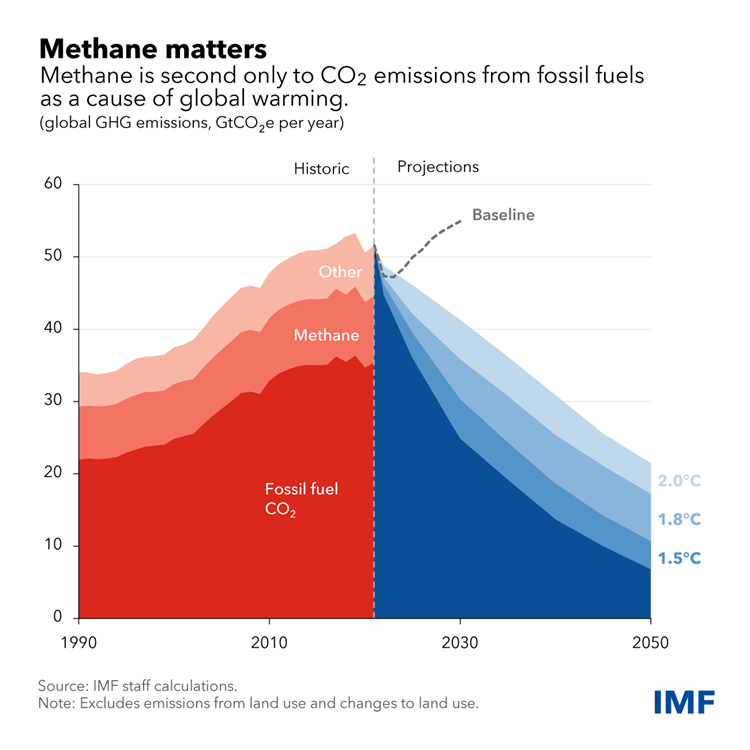

When we talk about greenhouse gas emissions, many of us are really just talking about carbon emissions. And it makes sense – carbon dioxide is responsible for 75% of global warming.

But we often overlook methane (CH4), a gas contributing to a further 20% of warming. Its impact may have been even bigger since the Industrial Revolution, with scientists saying it’s made up 30% of total warming since that period.

However, unlike carbon, the largest source of anthropogenic methane emissions isn’t fossil fuel production – it’s the food system. Agriculture already accounts for a third of all greenhouse gas emissions. Nearly half of these come from carbon dioxide, and 35% are from methane.

Methane emissions are rising faster than ever before, growing by as much as 20% between 2000 and 2020. And if we don’t take any action, human-caused methane emissions will rise by up to 13% between 2020 and 2030, taking the world in the opposite direction on the path to 1.5°C.

So addressing methane is critical to the climate fight. According to the UNEP, anthropogenic methane emissions can be cut by 45% within the decade, which alone would avert almost 0.3°C of temperature rises by 2045.

With the food system’s outsized impact on methane – and vice-versa – it is vital to consider just what we can do to fix the situation, and what solutions companies and governments are looking into.

How does methane harm the environment and human health?

Methane has a much shorter lifespan (12 years) than carbon, but it’s much more efficient at trapping radiation. Scientists have found that methane is 86 times more potent than CO2 over a 20-year period, and has a warming impact 28 times stronger over 100 years.

Methane is the primary contributor to the formation of ground-level ozone – higher methane emissions account for half of the global rise in tropospheric ozone levels. Ozone is a hazardous pollutant and greenhouse gas, and causes a million premature deaths every year.

So by reducing methane, we can curb ozone, which could prevent 260,000 premature deaths, 775,000 hospital visits for asthma, and 73 billion hours of lost labour from extreme heat every year.

What are the worst contributors of methane emissions?

Human activity is the main source of methane emissions, amounting to 60% of the global total – the rest comes from natural causes. Agriculture is the biggest polluter here, the source of 40% of anthropogenic CH4 emissions, according to the Global Methane Budget (which is yet to be peer-reviewed).

Within this, meat and dairy production is by far the worst offender, accounting for 25-35% of total human-caused methane emissions. This is thanks in large part to livestock’s digestive processes, called enteric fermentation.

Since cattle are ruminant animals, they have specialised digestive systems, allowing them to digest foods that humans and most other animals can’t. When food enters their stomach, microbes and bacteria break down the particles, which ferment in a part of the stomach called the rumen. As this process takes place, these food particles produce methane.

Every time cows belch or flatulate, they emit methane into the atmosphere. To understand just how much this gas is central to cattle emissions, consider this: if we removed the warming effects of methane, the greenhouse gas footprint of beef production would be halved.

In addition to livestock, rice cultivation also plays a major role here, emitting 8% of methane from human activities. And aside from agriculture, waste accounts for up to 20% of anthropogenic methane emissions – this involves food waste, wastewater, and organic materials in landfills.

How does methane affect the food system?

Okay, so agriculture has a major impact on methane emissions. But how does CH4 itself affect our food system?

Methane’s contribution to climate change can lead to a change in growing seasons, increase the prevalence of pests and diseases, and decimate crop yields. Research has shown that through its contribution to ozone formation, methane is responsible for staple crop losses of 15% per year.

This illustrates methane’s role in growing food insecurity – 10% of the world goes hungry every day. With the world population expected to reach 10 billion in 2050, the demand for food will soar in tandem, worsening food inequities and creating more hunger.

Methane emissions from wetlands also impact water availability, a major problem for the food system considering agriculture accounts for 70% of all freshwater withdrawals. There’s an effect on land use too – reducing methane emissions could free up over 350 million hectares of land by 2050, which could then be used for carbon sequestration and habitat protection.

Curbing methane emissions is crucial to limiting climate feedback loops like the melting of the polar ice caps and the rise of sea levels. By accelerating warming, methane exacerbates climate change’s impacts on the food system, destroying crop yields, reducing food quality and access, weakening soil health, altering ecosystems, and lowering farmer incomes while subsequently raising food prices.

What solutions exist, and which food-focused startups are fighting the problem?

So what can we do? Experts say there are a host of measures we can take to cut out methane and its impact on our lives.

Many advocate for improved livestock feed. Current crops like corn and soy take up a lot of land and are responsible for vast amounts of deforestation, and feeding them to animals that are then eaten by humans isn’t an efficient use of resources. Quick and large-scale implementation of enhanced livestock feeding mechanisms can bring down global methane emissions by 20% by the end of the decade.

The WWF has expressed support for better feed systems as a lever for the food system’s sustainability improvements. Many of the startups aiming to reduce livestock-derived methane emissions are betting on seaweed, such as Rumin8, Sea Forest, Symbrosia, and CH4 Global.

This idea is based on a study that proposed an over 80% reduction in methane emissions when you put a type of red seaweed in livestock feed – however, a subsequent trial showed that this only amounted to a 28% cut in methane. Scientists are also aiming to figure out ways to manage manure more efficiently, whether that’s by composting it, covering it, or upcycling it into biogas.

There are other approaches to reducing livestock methane emissions too. Brightly calculates methane emissions from diverting food waste from landfills and converts them into high-integrity carbon credits (though this market faces a lot of scrutiny), Windfall Bio captures methane to transform it into organic soil, and Brightmark turns methane emissions from organic waste into renewable natural gas.

In terms of crops like rice, one of the most effective actions is to use an alternate wetting and drying approach, which can halve emissions. This involves irrigating and draining paddies two to three times throughout the season, as opposed to allowing continuous flooding, which helps limit methane production without impacting yield (while also requiring a third less water). Startups like AgriG8, Rize, MittiLabs and CarbonFarm are all aiming to decarbonise rice.

Finally, one of the most effective ways to cut out methane is to cut out meat and milk. Dietary shifts towards alternative proteins can help reduce the industry’s water footprint, free up farmland, and slash its emissions. Methane alone makes up 25-80% of livestock producers’ emissions – just think of the benefits a transition away from meat and dairy would present.

As carbon credits are called into question, and experts lay doubts over the efficacy of techno-fixes like feed additives and methane-cutting vaccines, alternative proteins are a surefire way to decrease methane from the air. Plant-based, fermentation and cultivated meat startups like Beyond Meat, Mosa Meat, Aleph Farms, Impossible Foods, and Meati are among the many players hoping to wean consumers off beef.

How are governments handling the issue?

While policymakers worldwide have been making promises about methane, many of them have been deemed ineffective or insufficient.

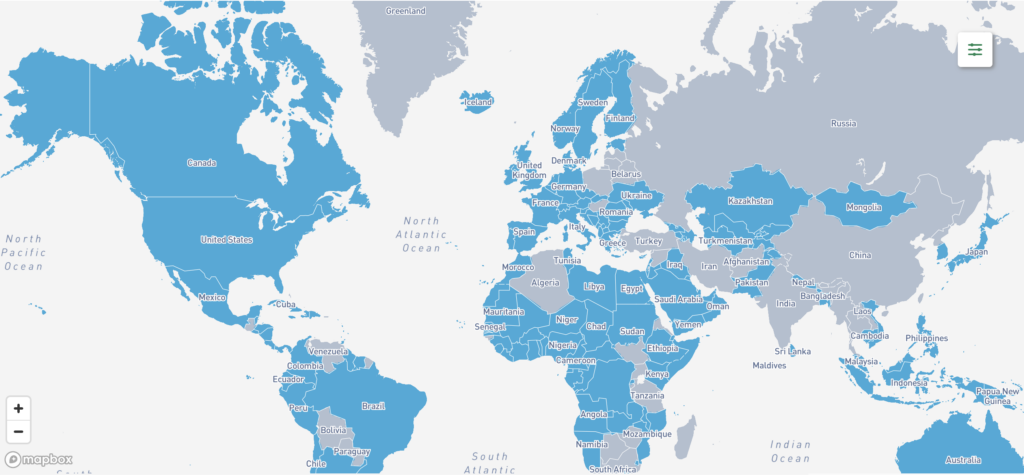

At COP26 in 2021, countries all over the world signed on to the Global Methane Pledge, which now involves 158 nations and the EU (representing over 50% of global methane emissions). The goal is to reduce CH4 emissions by 30% by the end of the decade, but this has been thrown into doubt.

In its agrifood roadmap presented at COP28, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) set a target for cutting livestock methane emissions by 25% by 2030. But the text was heavily criticised by a range of experts – and the FAO has a history of censoring its members’ work on methane.

Also at COP28, the US announced its intention to cut methane pollution from the oil and natural gas sector by 80%. But while this includes a $10M grant for the reduction of emissions from enteric fermentation (mostly for feed additives), the main focus wasn’t on agriculture, the primary source of methane emissions.

Then there’s the EU Methane Pledge, which lays out policies and activities to support the Global Methane Pledge. However, this strategy has been heavily shaped by livestock lobby groups, and the region’s overall efforts to curb methane pollution have been accused of falling short.

Meat and dairy lobbyists are highly influential in policymaking around climate change, and have been pushing governments to adopt a methane-reporting metric that vastly understates the actual emissions of the sector.

In a report uncovering the influence and misinformation efforts of the livestock sector, the Changing Markets Foundation has called on governments to implement national methane action plans, as well as support progressive policies like methane taxes, while food companies are urged to introduce ambitious methane targets.

Clearly, policymakers and business leaders need to do more to tackle methane pollution from the food system, which poses numerous dangers in an increasingly uncertain future for the health of the planet, its food system, and its people.