Plant-Forward Planetary Health Diet Can Lower Global Emissions by 17%

6 Mins Read

Following the Planetary Health Diet, which is rich in plant-based food and contains minimal animal proteins, can bring about a major shift in our carbon footprint.

Replacing red meat with nuts and legumes as part of a plant-forward diet can bring about a major shift in the food system’s climate footprint, a new multi-university study has found.

If everyone adopted the the EAT-Lancet Commission’s Planetary Health Diet – which advocates for more plants and whole foods, and less meat and dairy – decrease greenhouse gas emissions by a sixth.

Designed in 2019 as a way to feed 10 billion people and keep the planet healthy by 2050, the Planetary Health Diet recommends that fruits and vegetables should make up over half of people’s diets. As for the rest, more than a third should come from whole grains, plant proteins and plant oils, while dairy products and meat and seafood should make up only 3.6% each.

“The shifts of chief protein sources from animal-based to plant-based proteins according to the Planetary Health Diet would contribute the most to changes in footprints globally,” the researchers write.

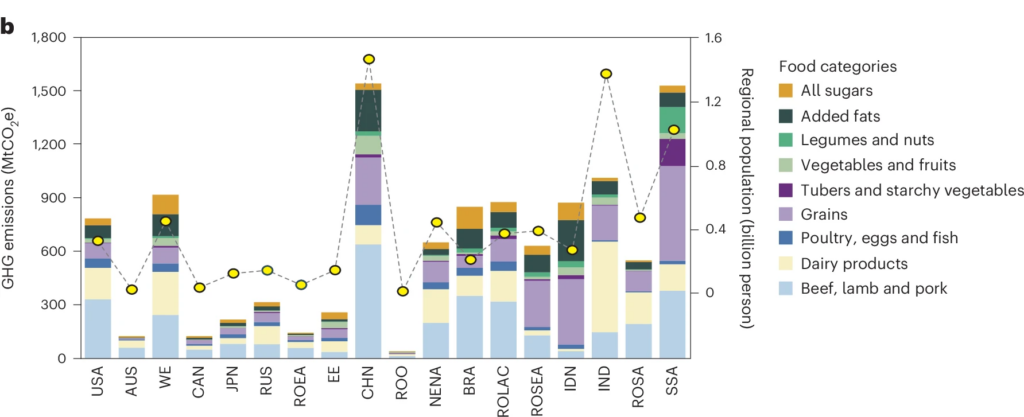

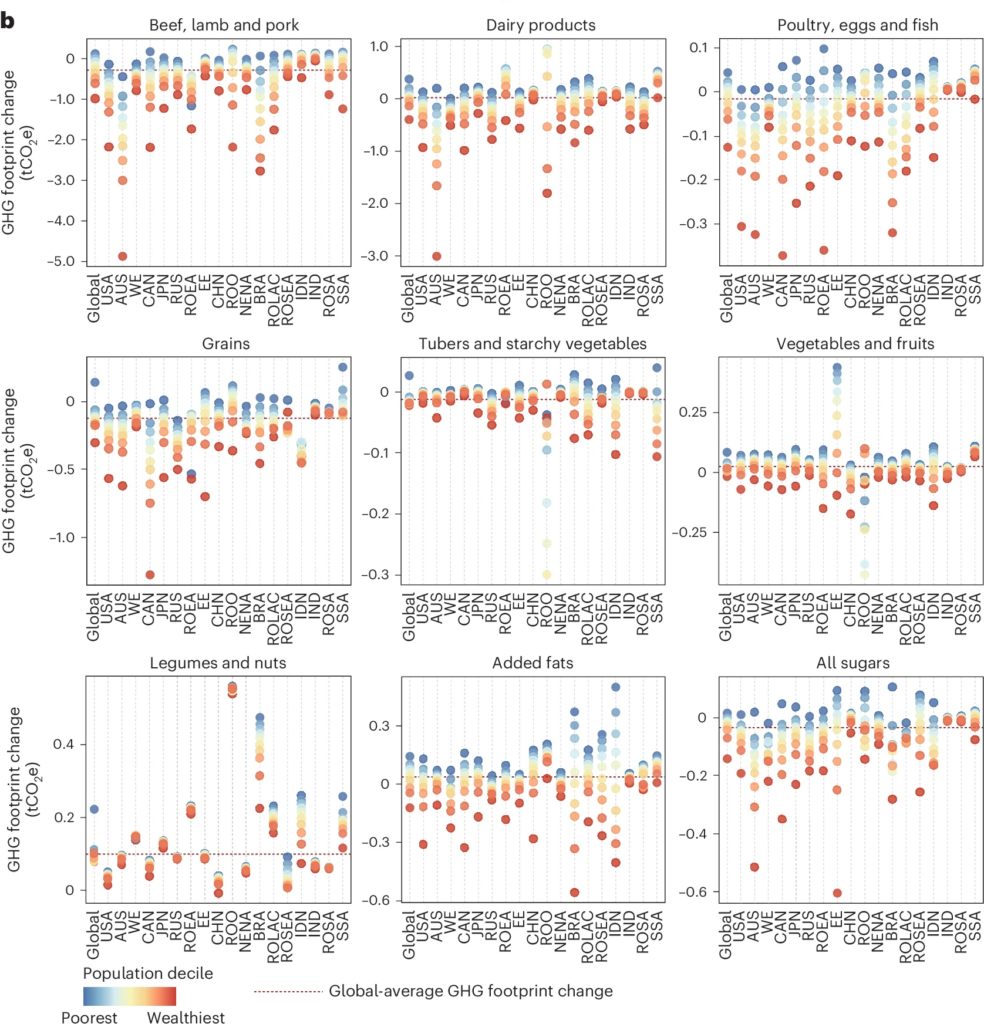

In the study published in Nature Climate Change, scientists highlight the inequality of our protein consumption and its associated climate impacts. Consumers in rich countries cause more emissions thanks to higher red meat and dairy intake, but they display lower levels of inequality compared to low-income nations, whose diets produce fewer emissions.

The research found that nearly 57% of the world’s population is overconsuming protein, but if this group of people adopted the Planetary Health Diet, it would bring about a 32.4% reduction in emissions. This offsets the 15.4% rise in dietary emissions that will come from a shift to healthy diets by underconsuming populations, resulting in a 17% decrease overall.

“We should look to reduce overconsumption of emission-intensive products in affluent countries, such as beef in Australia and the US, especially for wealthy consumer groups who are overconsuming, which would help to achieve significant health and climate benefits,” said corresponding author Yuli Shan, who noted that “animal-based products show greater potential for reducing emissions”.

The regional disparities in meat consumption and emissions

The study assessed the “unequal distribution” of dietary emissions from 140 food products in 139 countries or regions. It suggests that animal proteins account for 52% of dietary emissions, compared to 48% for plant-based products (in contrast with previous research that puts the former at 57%, the latter at 29%, with the rest ascribed to other land uses like cotton or rubber cultivation).

However, the gulf between their contribution to dietary consumption is vast, with plant-based foods supplying 87% of the world’s calories. Red meat is the most polluting food group, amounting to 29% of agricultural emissions but only 5% of its calories. Similarly, dairy contributes to 19% of emissions, but just 5% of calories as well.

Grains make up 21% of dietary emissions, but crucially, also provide 29% of global calories, highlighting the gap in efficiency between plant and animal proteins.

This is especially prevalent in high-income countries like Australia (where 84% of emissions come from meat and dairy) and the US (71%), despite animal foods contributing to less than a quarter of calories. Inversely, a majority of emissions in regions like Southeast Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa and Indonesia come from plant-based foods, albeit they’re also the source for most of their calories.

The researchers explain that in countries like Mongolia, where diets rely on red meat and dairy due to traditional nomadic lifestyles, such shifts may not be feasible. Instead, such areas could benefit from enhanced nutritional education.

For various reasons, many low-income countries can’t afford to move away from meat currently, so the biggest responsibility lies on developed nations, who are also the largest polluters. “Low-income countries face greater challenges in reaching healthier diets, with more than 1.5 billion low-income populations worldwide unable to afford the cost of the Planetary Health Diet,” says corresponding author Klaus Hubacek.

“Diet shifts need increased food consumption, but Sub-Saharan Africa, as well as South and Southeast Asia, have experienced stagnating agriculture production efficiency for decades and cannot produce nor afford to import the required food,” he explains.

“Agricultural efficiency must increase through various measures such as crop and soil management techniques and introduction of high-yielding crop varieties. But the proportions of nutrient-rich products in food imports must increase – alongside a reduction in restrictive trade policies which tend to raise food prices.”

Red meat the largest driver of livestock emissions

Lead author Yanxian Li says the objective of the study was to “assess the potential implications of emission mitigation of the food system resulting from changing consumer choices instead of forcing everyone to adopt the same diet”.

The suggested dietary shifts would mean a drastic change in the global calorie supply, with red meat slashed by 91%, all sugars by 72%, tubers by 76%, and grains by 50%. Meanwhile, consumption of legumes and nuts would need to be increased by 438%, added fats by 62%, and vegetables and fruits by 28%.

The proposed cuts in meat, eggs and fish consumption would lead to a reduction of 2.05 gigatonnes of CO2e – that’s more than the emissions of Indonesia, Germany and Canada combined. And 94% of this is driven by red meat. China is the largest contributor to dietary emissions (13.5%) – thanks to its large population and meat consumption – and it would also see the largest emissions cuts from red meat reduction (22%). This is followed by the US (15%) and Brazil (14%).

Overall, Uzbekistan (-74%), Australia (-70%), Qatar (-67%), Turkey (-65%) and Tajikistan (-64%) would benefit from the biggest decreases in dietary emissions, while Iraq would witness the largest increase (155%) if the world adopts the Planetary Health Diet.

As Hubacek alluded to, high costs remain the largest barrier for people in low-income countries to choose this diet. This is why these shifts “require tailored policies targeted at regions, countries, expenditure groups and products instead of ‘one-size-fits-all’ policies”.

In less affluent nations, policy efforts should focus on pricing interventions and technical assistance to reduce food costs and make it more accessible.

And in well-off countries, meat and carbon taxes – like the one in Denmark – could go a long way, as could eco-labelling and innovative menu designs to promote meatless foods. Increasing subsidies or tax breaks for plant-based food manufacturers would be highly beneficial too.

The study chimes with previous research extolling the climate credentials of plant-based food too. One analysis shows that vegan diets cut emissions, after pollution and land use by 75%, while another has found that replacing even 50% of meat with plant-based analogues can double climate benefits and halt deforestation.