9 Mins Read

Many have drawn parallels between alternative proteins and electric vehicles, but their disruption of conventional industries is far from the same. So how can the former learn from the latter?

“Elon Musk says they would have failed twice, if not for long-term low-interest government loans. There is no solar industry, there is no EV industry, there is no biopharma industry, if not for governments helping the companies that can’t qualify for standard bank loans, giving them long-term low-interest loans.”

That was Bruce Friedrich, president of alternative protein think tank the Good Food Institute (GFI), speaking at the cellular agriculture innovation day at Tufts University in January. He was comparing cultivated meat to the electric vehicles (EV) industry. “If the government gets the industry started, then the private sector can take over, just like electric vehicles,” he stated.

Friedrich’s statement has been echoed by many experts and stakeholders in the future food industry. And you can see why. Both are hoping to decarbonise highly polluting sectors – fossil fuels are the worst offenders, agriculture is second on that list.

EVs tackle a road transport industry that generates around 10% of global emissions. Alternative proteins go even further, aiming to displace an animal agriculture sector that produces between 11-20% of all emissions. But the disparity between the two sector’s impact to date is stark.

Between 2012 and 2023, the sales share of EVs went from 0.2% to 18%. But plant-based meat, which began its current wave around a decade ago too, still only accounts for 0.9% of the entire meat market (plant-based milks, at 14.5%, fare better).

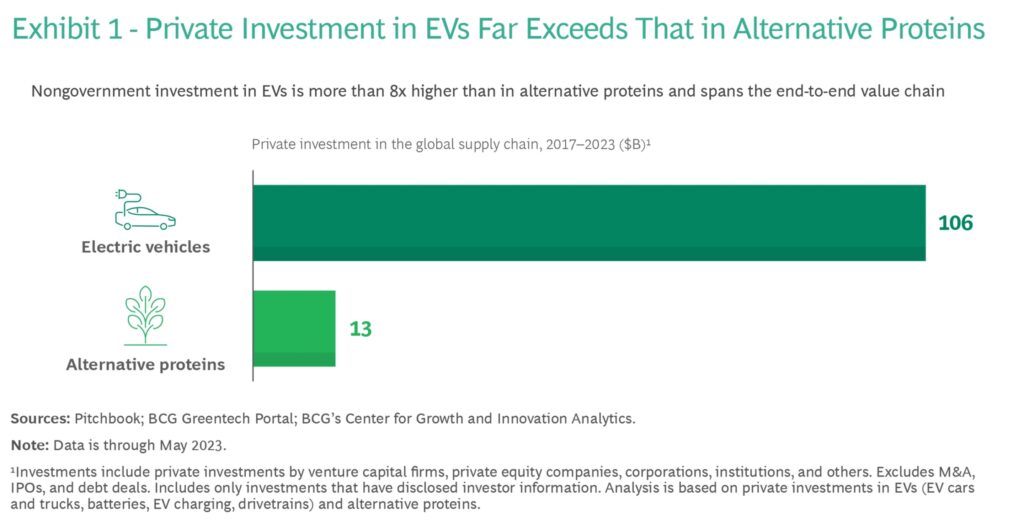

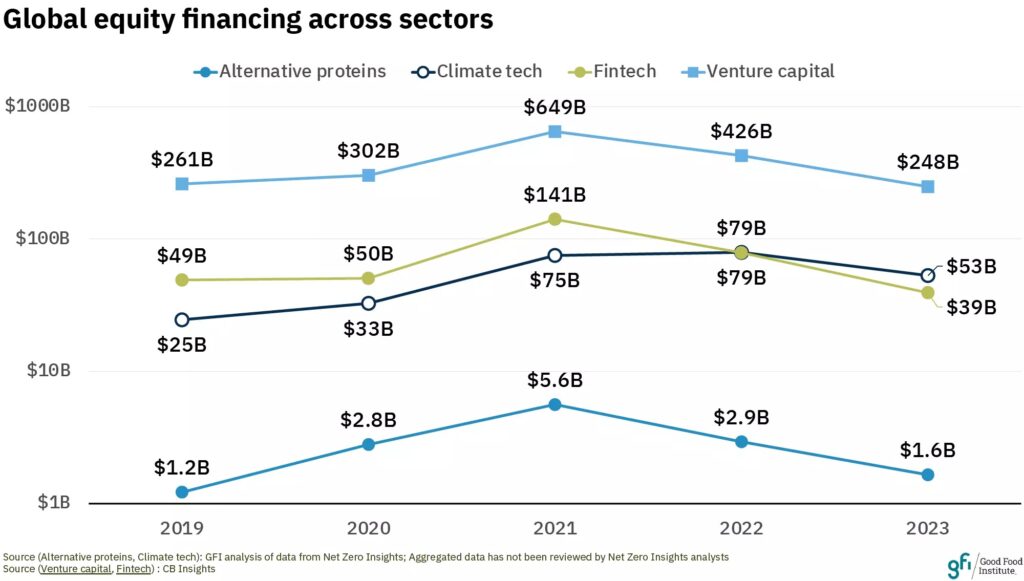

People were apprehensive about both technologies in the beginning, but only EVs lit up investors’ eyes. The sector received $106B in private sector capital from 2017-23 – that’s more than the GDP of many countries, and over eight times what the alternative proteins sector got in the same period ($13B).

The trend is similar across public investment too. In 2022, EVs received $40B in direct purchase subsidies, but governments only pumped $635M into the novel protein sector.

Change is needed, and fast. “Alternative proteins are one of the most effective technologies we have to reduce the environmental costs of our food systems. Unfortunately, this area is not moving at the speed necessary to combat climate change, and is far behind advances in the energy sector,” says Hannah Ritchie, deputy editor of Our World in Data.

So what lessons can alternative protein companies take from their EV counterparts? It’s a question explored by the Boston Consulting Group (BCG), GFI, and Synthesis Capital in a new report. Here’s what it suggests.

Price parity is paramount

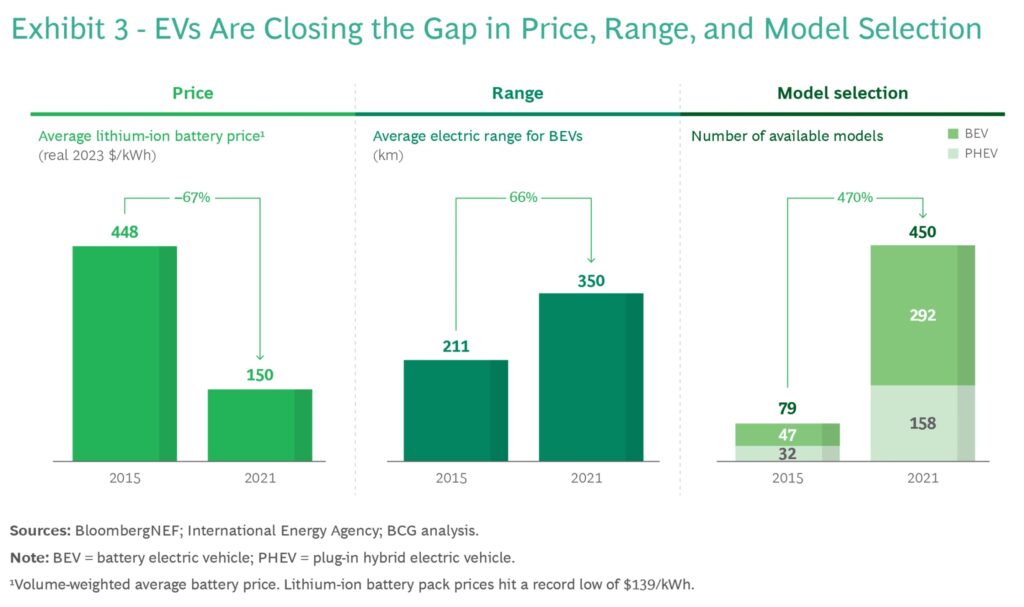

EV manufacturers have used the capital to make better and cheaper models – the cost of lithium-ion batteries was slashed by 67% from 2015 levels in just six years. Alternative proteins have a huge gap to fill here.

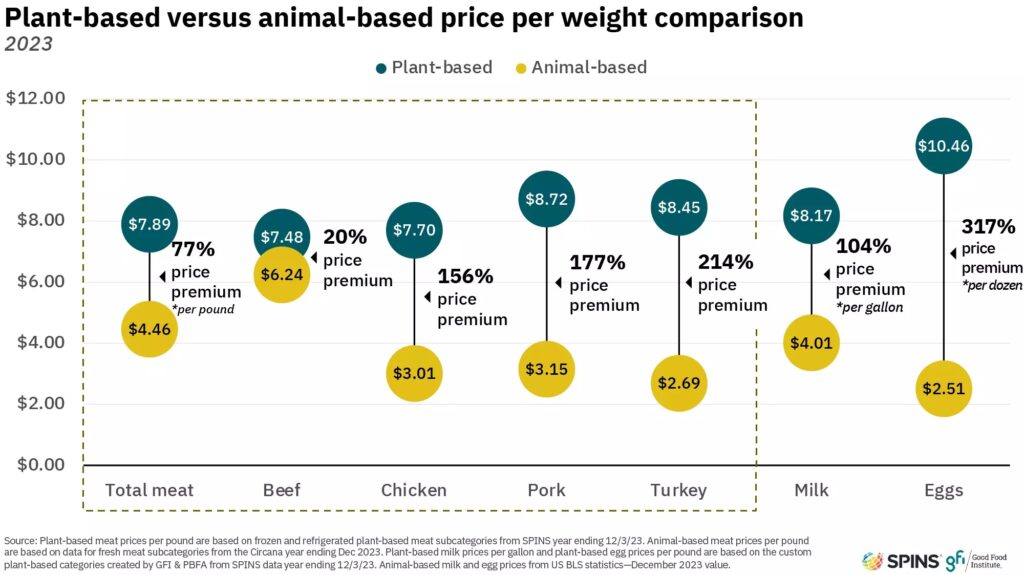

Cultivated meat is still years away from being cost-effective, but even with plant-based meat, the product that comes closest to its animal counterpart is beef. Still, plant-based beef is 20% more expensive, according to GFI. Overall, vegan meat analogues cost consumers 77% more on average, while plant-based milks have a 104% markup.

Granted, EVs are a high-cost investment usually made once every few years. In contrast, people have “hundreds of opportunities each year” to choose their preferred food at supermarkets and restaurants. But what EV makers have done well is to sell sustainability as an “and” instead of “or”, by making their cars competitive on cost, range and models.

The novel protein industry needs to do the same. Companies need to appeal not just on the sustainability front, but also speak to people’s core food needs. It means prioritising taste and texture just as much as price and convenience. “The goal is to make alternative proteins a choice rather than a compromise. This way, sustainability becomes a sweetener, not a sacrifice,” the report argues.

This is exactly what initiatives like the Bezos Earth Fund are trying to tackle. It has committed $1B to the future of food, $100M of which is going to three alternative protein research centres, two of which are already live in the US and the UK.

Andy Jarvis, the fund’s food programme director, told Green Queen earlier this month: “You’ll have no sustainability impact, unless the price and the taste are on parity – that’s an absolute necessity… What we need is something that is going to be attractive as a value proposition to carnivores. For that, it needs to cost the same or less, then it needs to taste just as good or better. That’s the bottom line.”

Just like successful EV companies have delivered great cars with unique-to-them features, low ownership costs, and advanced software and safety tech, alternative protein producers will need to close the taste and price gap, and then “out-innovate existing food companies”.

Technology will help, giving this sector a competitive advantage over animal-derived meat – think products with enhanced nutrition or functional ingredients. Companies can bring flavours unavailable to consumers at present, and personalise products to address allergies, health conditions and other dietary needs.

Governments need to back alternative proteins more

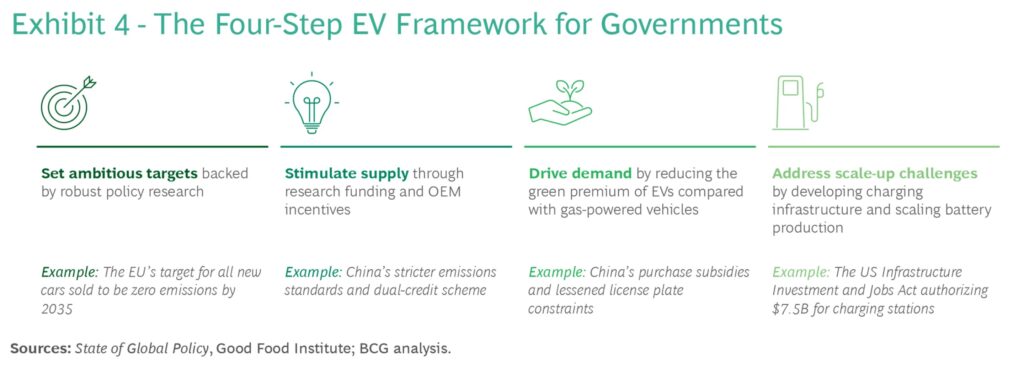

Public sector support has been crucial to the rise of new technologies like clean energy and EVs. The report points to a four-stage framework adopted by governments, which includes setting ambitious targets, stimulating supply, driving demand, and addressing scale-up challenges.

Take the EU, for example. Its Fit for 55 standards mandate a 55% emissions reduction from cars by 2030 (from 1990 levels), and that new models need to be zero-emission by 2035. Governments have created some goals for alternative proteins, but the authors say much larger commitments are needed.

One instance of such ambitious target-setting comes from Denmark, which recently approved the world’s first carbon tax on agriculture. It will cost the average farmer about $100 a year for each cow. And while this directly addresses livestock emissions only, the country last year also became the first to adopt a national action plan to promote plant-based foods.

Then there’s China’s stricter emissions standards and dual-credit policy, which financially rewarded carmakers that met their EV quotas. In contrast, government investment into alternative proteins has been modest, though much of the $180M allocated for R&D in 2022 went to publicly accessible research grants. Funding open-access research that helps producers can enable them to scale up.

Also in China, lawmakers offered purchase credits and streamlined licenced plate registration for EVs during Covid-19 to drive demand. Governments can do the same with cultivated meat through regulations that help bring novel proteins to market.

“As the industry grows and applications for market approval increase, governments must be prepared to evaluate alternative products quickly,” the report states. Additionally, most research focuses on taste, texture and price, but more work is needed to address other concerns, including health and variety.

In the US, the EV industry received $7.5B of public capital in 2022 to build more charging stations. In a similar vein, governments can help alternative protein startups build more labs and add capacity, which will keep countries competitive in the food system transition.

Public and private investment must increase

“The success of electric vehicles shows how fast public and private investment can catalyze green innovation. Forward-thinking governments and food companies now have the opportunity to replicate that success for alternative proteins,” said Lewis Bollard, programme director for Open Philanthropy.

VC funding for alternative proteins was down by 44% last year, and even the $635M that governments invested in 2022 is a fraction of what the industry really needs. BCG analysis has previously suggested that nearly $30B and $11B billion are required just to build the critical bioreactors and extrusion capacity, respectively, to produce sausage links, patties, and other products affordably.

“Just as EV makers needed to invest heavily in tooling, software development, and emerging battery technologies to succeed, alternative protein companies require funding to continue researching new food technologies, including cell cultures and precision fermentation,” the report reads.

Alternative protein companies need support across the value chain, helping them identify, develop and build industrial-scale manufacturing processes and facilities for texturising, extruding, and 3D-printing proteins.

Businesses themselves need to invest in the full spectrum of activities, from early research and infrastructure support to ingredient sourcing and consumer sales, to cut costs, overcome bottlenecks and increase access to their foods.

Looking to China once more, its government doubled down on credits and tax breaks between 2009 and 2022 to become the global EV leader. Such investments can attract private funding, and a dual public-private approach also builds market confidence.

State-backed research institutes could collaborate with alternative protein startups on R&D projects, or more public-private partnerships could fund infrastructure to support production and distribution.

What’s next for alternative proteins?

The alternative protein sector has had its fair share of criticism over the last two years. Parts of the media have blasted it, and some legislators have restricted progress by putting bans on product labelling and cultivated meat altogether.

“It is worth noting that the field has seen more technological advancements and cost reductions than most other disruptive technologies over the same duration of time,” counters Viknish Krishnan-Kutty, founder and CEO of Singapore-based Cellivate Technologies.

The report asks governments to build supportive policies that leverage the four-step framework, help companies fund R&D, secure raw materials, and build infrastructure – all of this will help move the affordability needle.

VCs must channel their dollars across the entire value chain and encourage companies to devote sufficient resources to R&D to cut the gap with conventional proteins.

If you’re an existing food company, innovating early can help you get a competitive advantage, allowing you to set industry standards and reset consumer expectations. And as for alternative protein startups, launch products that deliver “excellent taste, desirable texture, competitive prices, and utmost convenience”.

The report suggests that replacing half of our meat and dairy consumption with alternative proteins can cut five gigatons of CO2e annually, the equivalent of taking half of all gas-fuelled cars off the road.

Emma Ignaszewski, senior associate director of industry intelligence and initiatives at GFI, and one of the report’s authors, sums up the EV-alternative protein relationship best. “Electric vehicles are a powerful climate solution that doesn’t require consumers to make significant behavioural changes. They simply offer a more sustainable swap-in for gas-powered cars,” she says.

“Alternative proteins offer a strikingly similar promise: enjoy your burger, but produced with far lower greenhouse gas emissions than conventional meat,” she adds. “Competing on these drivers of consumer choice is the blueprint for alternative proteins to help decarbonise the food sector, just as electric vehicles can help decarbonise the transportation sector.”