Beer Proteins: Researchers Develop Method to Extract Protein from Brewers’ Spent Grain

5 Mins Read

Researchers have come up with a way to extract useful proteins through leftovers from beer production, which could help reduce waste and produce a circular, more sustainable source of protein.

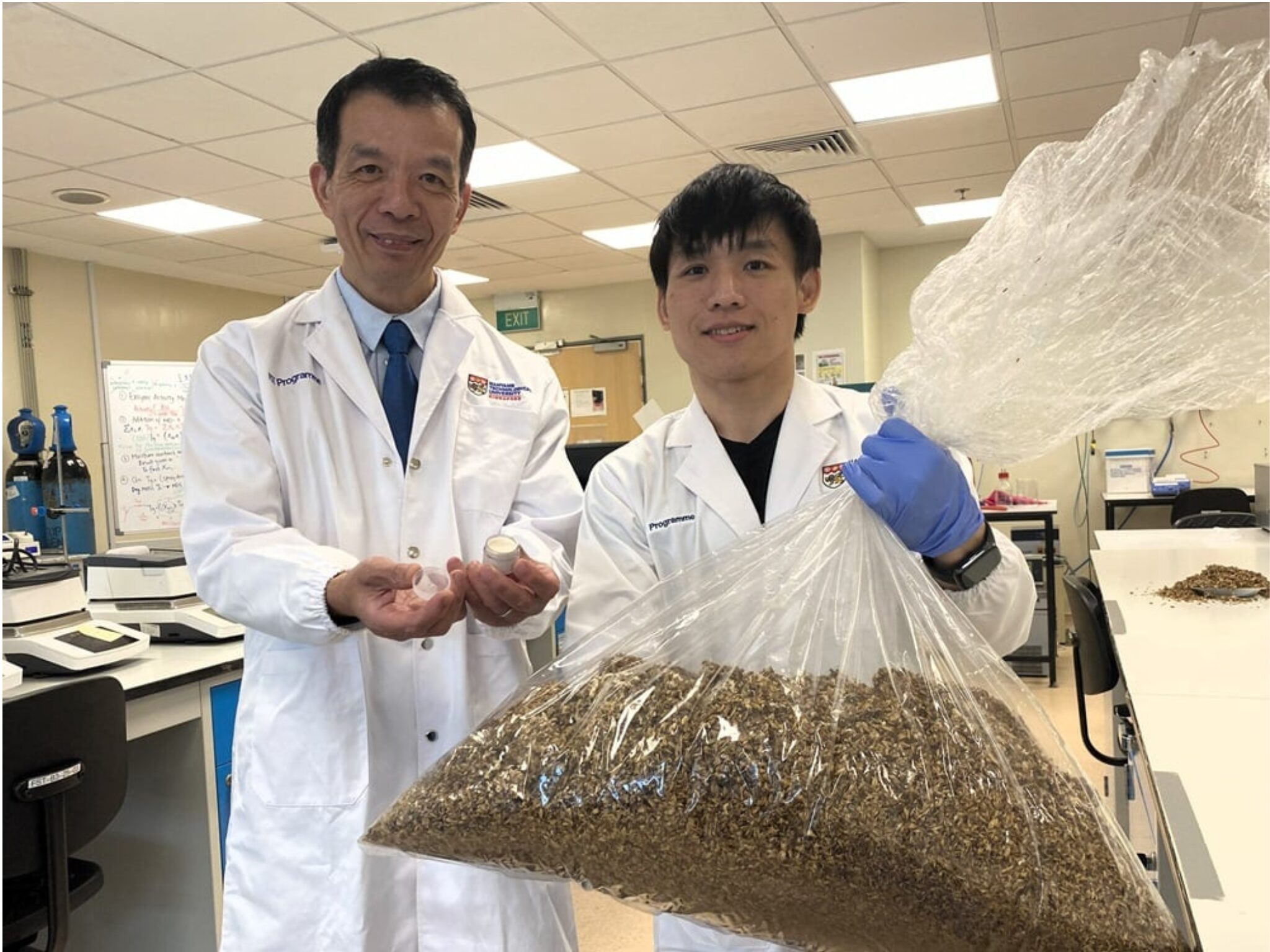

Would you eat the beer industry’s byproducts? That’s what researchers at the Food Science and Technology Programme at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University (NTU) are proposing, having developed a method to extract over 80% of the proteins available in brewers’ spent grain (BSG), which is left over from the production of beer.

The solid residue from malted barley after brewing beer, BSG makes up 85% of the waste emanating from the brewing industry – each year, 36.4 million tonnes of the byproduct is manufactured globally. But while some are repurposing BSG for animal feed (accounting for 70% of its use), biofuel production or compost, a substantial portion still ends up in landfill, emitting harmful greenhouse gases like methane and carbon.

But using up the beer industry sidestream as a protein source could reduce the amount of gases released into the atmosphere, cut food waste, address humans’ protein needs, and tackle food shortage and insecurity globally, according to the study published in the peer-reviewed journal Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies.

This was echoed by programme director and lead researcher William Chen, who said: “Our study, which presents more sustainable and efficient ways to add value to brewers’ spent grain disposal, is a crucial step towards mitigating its contribution to greenhouse emissions and reducing environmental strain, while also enriching the global food supply chain.”

How researchers turned brewers’ spent grain into proteins

To produce the proteins, NTU collaborated with beer giant Heineken’s Asia-Pacific division, which produces Tiger Beer (the leading beer in Singapore, with a 19% market share) and provided its BSG for the study.

The researchers sterilised the BSG before fermenting it with Rhizopus oligosporus, one of the fungi strains used to produce tempeh. The three-day fermentation process breaks down the BSG’s complex structure, making its protein content more easily extractable.

This is then dried, ground into a powder, filtered and spun in a centrifuge to separate the protein, which floats to the top, away from the rest of the mixture. Once extracted, these proteins can be used directly in supplements, added to plant-based foods to boost their protein content, as well as enhance the shelf life and boost the moisturising and antioxidant properties of lotions or creams.

“Demonstrating that the protein-rich qualities of brewers’ spent grain could be successfully extracted and funnelled into supplements and enriching plant-based proteins to make them more attractive to the consumer addresses two global pressure points – food wastage and food shortage,” said Chen.

Given that the BSG proteins are rich in antioxidants, they can protect our skin from pollutants, and present an eco-friendly alternative to conventional cosmetic components like parabens, which disrupt hormone function in aquatic animals, and petroleum-based ingredients, whose extraction and production carry a heavy climate impact.

Highlighting these cosmetic applications of the protein, co-author Chai Kong Fei said: “Due to their natural exfoliating properties and abundance of antioxidants, we feel they could be incorporated into various skincare formulations, from moisturisers to body lotions, offering an alternative to chemicals such as preservatives, which have been shown to cause damage to wildlife and the environment after being washed down our sinks.”

NTU plans to scale up and commercialise BSG proteins

The authors note how the fermented BSG proteins can be used to grow an increasingly hungry planet. By 2050, the global population is set to reach 10 billion, with meat consumption set to increase by 73%. But this is unsustainable, both in practice and for the planet – meat production generates twice as many GHG emissions as plant-based foods, and scientists say emissions from livestock farming must be halved by the end of the decade.

Animal-derived foods also only account for 18% of calories and 37% of protein globally – and as 780 million people face hunger around the world, and a third of all food goes to waste, more efficient and sustainable protein sources are paramount.

The researchers at NTU managed to extract up to 200g of protein per kg of BSG – this means if all the world’s BSG could be fermented to produce proteins, we could have an additional 7.28 million tonnes of protein on our hands every year. In Singapore alone, the average woman and man require 146kg and 204kg of protein each year. These BSG proteins are safe for consumption, and incorporating them into plant-based foods could enhance the nutritional value and help meet daily protein requirements more efficiently.

The extracted proteins also feed into growing consumer preferences for sustainably sourced and eco-friendly products, with 66% of global consumers happy to pay more for products from brands committed to sustainability, according to Nielsen.

“Innovative applications of underutilised grains like those being brewed up at NTU have the potential to reduce Singapore’s dependence on raw-material imports, provide an additional revenue source for local producers, and help entrepreneurs craft more nutrient-dense plant-based meats,” said Mirte Gosker, managing director of alternative protein think tank the Good Food Institute Asia-Pacific. Singapore currently imports 90% of its food supply, but the government has set out a goal to make 30% of its food locally by 2030. “Amid rising food demand pressures, protein extraction from agricultural sidestreams is field-primed and ready to be tapped.”

The team at NTU, which was the first APAC university to offer an undergraduate course focused on alternative proteins and cultivated meat, is in further talks with Heineken Asia Pacific to scale up the protein extraction method. Moreover, it plans to collaborate with food, beverage and cosmetic companies to incorporate its technology with an eye towards commercialisation.

“Our method presents an innovative way to repurpose beer waste into a valuable protein source for global nutrition,” said Chen. “Beyond mere innovation, our work embodies a narrative of turning what was once considered waste into a vital resource, a symbol of sustainability, and a solution to one of humanity’s most pressing challenges: protein scarcity.”