Report Says Europe Not Prepared for ‘Catastrophic’ Climate Impacts, But Fails to Highlight Livestock Farming

6 Mins Read

The first risk assessment of the impact of climate change on Europe puts the urgency of action into sharp focus – but the lack of a spotlight on livestock farming is a huge miss.

2023 was the warmest year on record, and last month was the hottest February ever recorded. In fact, between February 2023 and January 2024, the average global temperature exceeded preindustrial levels by 1.5°C.

We’re way past 1.5°C as a climate target now, especially given that even if we manage to somehow stick to that limit by the end of the century, the climate risks faced by Europe will not diminish. The continent is the fastest-heated in the world, with temperatures rising more than any other continent since the Industrial Revolution – its heating rate is actually twice as fast as the global average since the 1980s.

With extreme heat causing between 60,000 and 70,000 premature deaths in Europe in 2022 alone, that number could proliferate greatly as climate change is a risk multiplier. The continent is not prepared to deal with the consequences, which could mean hundreds of thousands of deaths, and €1T in annual economic losses just from coastal floods.

That’s the consensus of the European Environment Agency’s (EEA) first major risk assessment report, which warns that most climate hazards will continue to increase in Europe, even under the most optimistic scenarios of the 2015 Paris Agreement.

“Our new analysis shows that Europe faces urgent climate risks that are growing faster than our societal preparedness,” said EEA executive director Leena Ylä-Mononen. “To ensure the resilience of our societies, European and national policymakers must act now to reduce climate risks both by rapid emission cuts and by strong adaptation policies and actions.”

Europe faces multitudes of climate risks

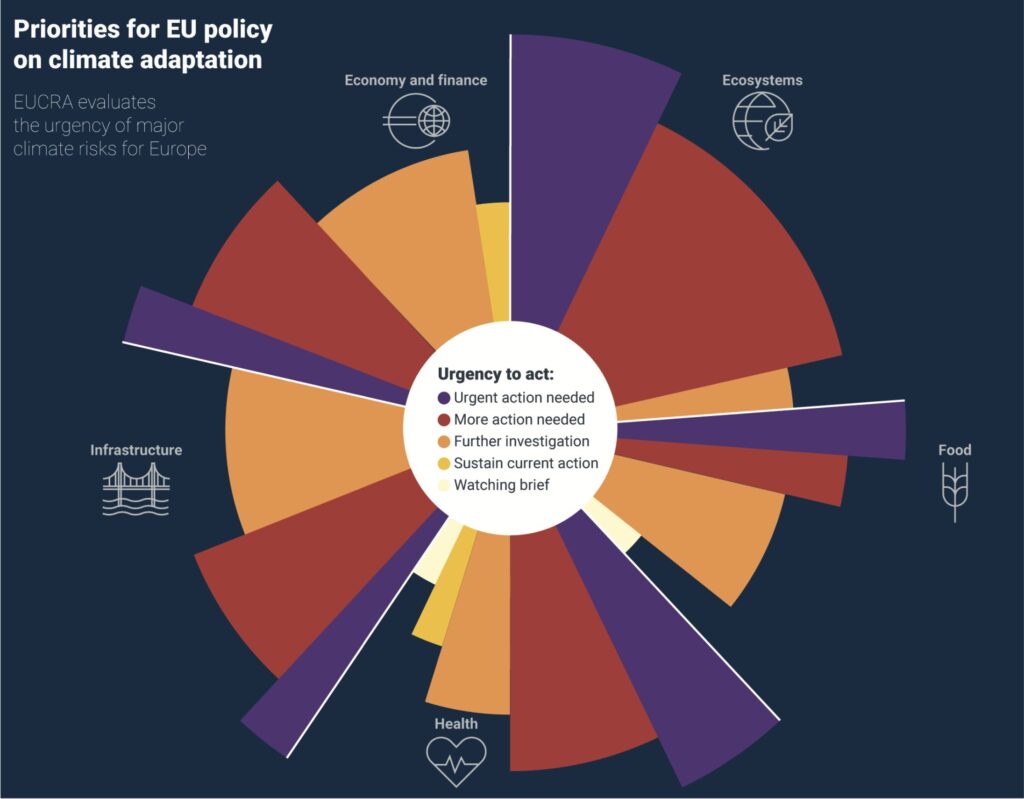

The report identifies 36 significant climate risks, grouped into five broad clusters: ecosystems, food, health, infrastructure, and economy and finance. These are also classed as cascades – climate impacts can cascade from one region to another, and the risks they represent can bring system-wide challenges that affect entire societies, particularly vulnerable social groups.

For example, climate impacts on food production can cascade to rural and coastal livelihoods, land use and the health of vulnerable people, which itself can affect labour productivity and resource needs of the medical system. Damages to terrestrial, freshwater and marine ecosystems could spell trouble for food production and security, animal and human health, land use, and infrastructure – impacts on the latter affect nearly all aspects of society, the report argues.

“If decisive action is not taken now, most climate risks identified could reach critical or catastrophic levels by the end of this century,” the report reads.

Of those 36 risks, 21 are associated with “potentially severe consequences across Europe” and need more action now, while eight need particularly urgent attention. There are regional discrepancies too – three of these eight urgent risks are evaluated because of their high severity in southern Europe, which is one of the hotspots of climate change impacts in Europe, alongside low-lying coastal areas and the outermost regions of the EU.

The highest number of urgent risks belongs to the ecosystems cluster, concerned with coastal and marine ecosystems and threats to biodiversity and carbon sinks due to wildfires. In the health cluster, heat stress and wildfire-related risks to the general and built environments (particularly in southern Europe) are the most pressing, while flooding caused by rain or rivers is the most urgent infrastructural threat. The EU’s solidarity mechanisms face the biggest risk in terms of the economy and finance, with its solidarity fund for recovery already being oversubscribed in recent years.

EU urges ‘partial’ plant-based shift, but fails to call out livestock farming

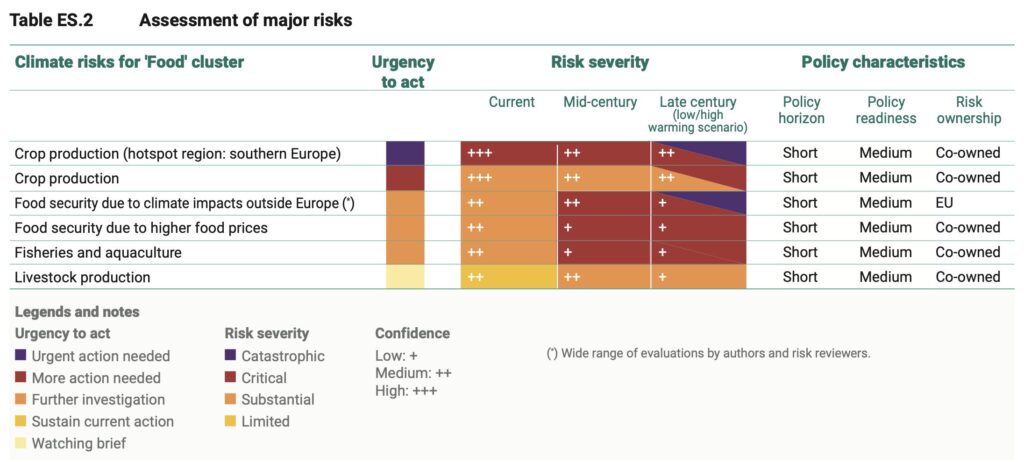

Meanwhile, risks to crop production (especially in southern Europe) are the most urgent and severe in the food cluster. Climate impacts outside Europe and higher prices mean more action is needed to address food security too, which has a ‘substantial’ risk severity, as do fisheries and aquaculture. However, the EEA’s report fails to highlight the impact of livestock farming, which it brushes aside as a ‘watching brief’ with no urgency to act and limited risk severity at present. Even at mid- and late-century levels, the risk intensity is described as substantial, instead of critical or catastrophic.

This is surprising given that animal agriculture is responsible for 11-19.6% of global greenhouse gas emissions, with the UN FAO revealing last year that livestock farming makes up about 40% of the food system’s emissions. Another UN body, the UNEP, published a landmark report during COP28, which touched upon how the livestock industry contributes significantly to human-caused climate change, widespread water and air pollution, loss of soil structure and nutrients, and loss of terrestrial, freshwater and coastal biodiversity.

The EEA notes how megadroughts, late frosts, heavy rain, excessive heat, pests and diseases can lead and have already led to crop failures and reduced yields, critically impacting food production in southern Europe in particular. Italy and Spain, for example, experienced lower yields of tomatoes, peaches and nectarines.

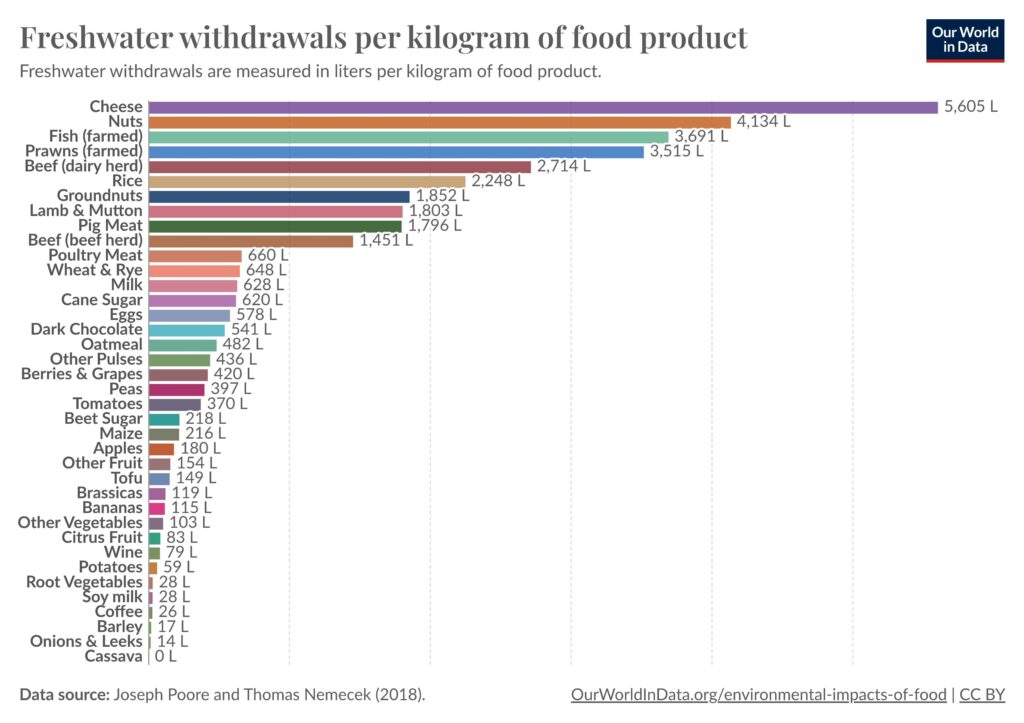

The report outlines the need to support drought-resilient and less water-intensive crops, with more efforts required to raise awareness about the risks of water-heavy food production. It’s a little ironic considering that the EU itself could do with greater awareness here: animal-derived meat like farmed seafood, beef, lamb and mutton have some of the highest water footprints among foods, while cheese tops the list (followed by nuts).

It must be noted that the EEA does identify shortcomings in the EU’s food policies, noting how its common agricultural policy and common fisheries policy don’t address climate risks and adaptation needs adequately. “The transition to more climate-resilient and sustainable food systems in Europe requires actions at many levels, from farms to national and EU policies,” it states. “EU policy and governance has a critical role to play to support and accelerate this transition, such as by better coordinating actions at territorial level.”

The report addresses that a “partial shift” from animal- to plant-based foods can reduce freshwater consumption, in line with the Farm to Fork Strategy and in line with international dietary guidelines. Separate studies have shown that veganism can reduce emissions, water pollution and land use by 75% compared to a meat-rich diet, and swapping just half of your meat and dairy consumption can slash water use by 10%.

The lack of focus on the impact of livestock is a glaring issue, though hardly surprising. The EU injects 1,200 times more funding into animal agriculture than alternative proteins, with cattle farmers receiving 50% of their income through direct subsidies from the bloc. It has also U-turned on its promised caged farming ban. Meanwhile, the EEA report mentions “eutrophication from agricultural fertilisers and livestock” as an important stressor in certain hotspots, but the EU itself has been influenced by lobby groups to push back on its green agriculture reforms around pesticide use and Farm to Fork strategy.

To curb the impact of climate change, the report suggests a systems-based approach to adaptation and resilience-building, notes the importance of addressing underlying social drivers of climate risks, outlines the need for collaboration between member states, and states that strong policy action is urgently needed, alongside improved risk analysis through legislation, monitoring, funding and technical support.

But there’s nothing about livestock agriculture – or food systems, for that matter. That is potentially catastrophic in itself.