Fermentation-Brewed Proteins: Farmless Raises €4.8M in Seed Funding for Pilot Plant & NPD

5 Mins Read

Dutch fermentation startup Farmless has secured €4.8M to fund a pilot plant and accelerate R&D for its landless microbial protein. Founder and CEO Adnan Oner speaks to Green Queen about the investment round and plans for regulatory approval.

In total, Farmless has raised €6M, after a €1.2M pre-seed round earlier this year. The oversubscribed seed round was co-led by World Fund and Vorwerk Ventures, with participation from Revent.

The company creates climate-friendly functional proteins with a complete amino acid profile, employing a biomass fermentation technique that relies on liquid gases as feedstock. Its tech platform is designed “from the ground up” to be cost-effective, simple and efficient.

“Moving away from sugar as a feedstock for fermentation represents a significant opportunity to reduce CO2 emissions of fermentation-based food production,” said Dr Nadine Geiser, principal at World Fund.

Peter Schmetz, principal at Vorwerk Ventures, added: “We’re glad to back Farmless’s approach, which leverages molecular biology, food science and physics to develop superior food products that outperform its animal counterparts on all dimensions with significantly reduced climate impact.”

How Farmless grows its protein without farmland

Founded in May this year, Farmless aims to build a fermentation platform that can create “an entirely new food repertoire” by harvesting naturally occurring microorganisms through controlled fermentation with a replenishable liquid feedstock. The latter is key, as instead of using sugar – as Geiser referred to above – the company’s feedstock is made from carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen and renewable energy.

This allows Farmless to produce proteins locally, independent of agricultural land, which is important considering that half of all habitable land on the planet is used for farming, and 77% of that is for livestock production.

These proteins are made using liquid fermentation, a subsect of biomass fermentation. Unlike solid-state applications, where microorganisms are grown over an inoculated solid surface, microbial cells are submerged in a liquid for growth. It’s something that’s being used by large-scale manufacturers, most famously Quorn, the mycoprotein meat company. Farmless uses microorganisms that consume alcohol for its product.

“We source the feedstock from other companies that make it with CO2 captured from the air with green hydrogen [and] renewable energy,” Farmless founder and CEO Adnan Oner tells Green Queen. “The ammonia can also be made with green hydrogen. Additionally, we use a minimal quantity of micronutrients, very similar to those needed by plants.”

This feedstock is then turned into protein through microbial fermentation. “After fermentation, we separate the water and microorganisms efficiently through centrifugation and then dry it further,” explains Oner. “The end result is a whole food where we really use the whole organisms as the end product. The organism has a high protein content, ranging from 60-80%.”

The Amsterdam-based startup has already developed an initial protein product that can be used in meat, dairy and egg alternatives, through a protein platform designed to eventually “outperform animal-based proteins” on cost.

Climate impact, competition and regulatory approval

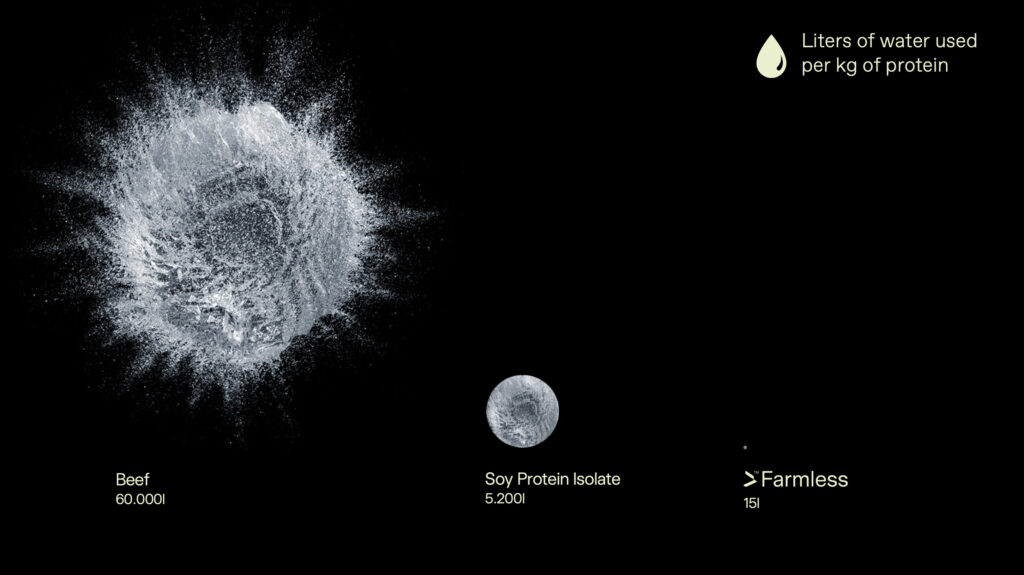

To measure the impact of its protein – which it claims is “carbon-negative” – Farmless conducted an internal life-cycle assessment (unverified by an independent third party). This revealed that the protein uses 15 litres of water per kg of protein (4,000 times less than beef, which uses 60,000 litres), needs no arable land (so about 5,000 times lower than beef, which uses 1,600 sq m per kg), and emits 2.2kg of CO2e per kg (227 times less than beef, which emits 500 kg of CO2e).

But it’s not just beef that Farmless’s protein trumps in terms of climate impact. Widely used in the plant-based industry, soy protein isolate – which is a pure protein extracted from soybeans – has a higher footprint too, using almost 350 times more water (5,200 litres) and 10 sq m of land, and producing nearly 3.5 times more GHG emissions.

Liquid fermentation certainly has its benefits, but it’s not an industry without challenges, which include – as Oner outlines – “scaling up the process specifically for your organism and finding the right equipment that makes the complete process efficient” and “finding non-dilutive capital to scale the infrastructure”.

Looking ahead

Farmless is “working on a B2B2C application where our protein is branded but we don’t sell to the end customer”, and the startup is currently exploring partnerships. Another thing it will need is regulatory approval, as its protein would be considered a novel food under EU regulations, which means it requires premarket authorisation by the bloc. This can be a slow process, which Oner feels is a “problem for the fermentation industry as a whole”.

But his company is in the early stages of prepping a regulatory filing, with plans to seek approval in multiple regions. “We have not yet submitted any regulatory dossiers and expect it to take one to two years before submission,” he confirms.

For now, the company will focus on recruitment and building a “pilot protein brewery” in Amsterdam to scale up its process. “We’re also setting up a substantial kitchen within the same facility. This space will be our creative playground, where we will play with, ferment and try out new food products – all under one roof,” he explains. “The pilot protein brewery will also enable us to produce a steady stream of samples for product co-development with partners.”

Multiple companies are working with novel proteins using gases in some form. For example, Finland’s Solar Foods – which closed an €8M funding round last month – makes Solein protein using CO2, hydrogen and oxygen; Air Protein – a subsidiary of Californian biotech firm Kiverdi – makes use of recycled carbon; and Austria’s Arkeon Biotechnologies taps into carbon and hydrogen for its microbial protein. Meanwhile, companies like NovoNutrients, Calysta (both Californian) and Deep Branch Biotech (UK) are producing air proteins for livestock and fish feed.

But Oner doesn’t see any of these as competition – Farmless’s big beef is with Big Beef. “Our direct competitors are legacy animal protein producers,” he notes. “We initially target the production of proteins with best-in-class functional properties that can be used in a variety of food products. We’ve chosen proteins because they can directly compete with animal products.”