Can AI Tech Fight Climate Change Without a Mega Emissions Footprint?

9 Mins Read

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly being used to better understand greenhouse gas emissions and develop tools to fight climate change – but it’s equally important to look at the tech’s own carbon footprint, and whether the emissions generated by all those large language models (LLMs) undo all its good work.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ve probably heard of Sam Altman in the last couple of weeks. The Open AI founder was ousted from the company, a lot happened, over 500 employees threatened to leave, and he was back as CEO sooner than you could follow the story.

It has become the most extraordinary tech story this year, given Open AI’s position as a leader in artificial intelligence following the launch of its wildly popular chatbots ChatGPT and GPT-4, which basically kickstarted a new tech revolution. Open AI has been a major factor behind the ascent of AI in our everyday lives – from text and image generation to research and relationship advice, AI has seeped into our routines.

AI models have been presented as a tool to fight climate change too, cutting down the need for travelling and saving hours of work by computing large amounts of data and helping improve climate models and sustainability goals. But there needs to be a conversation around AI’s own carbon footprint, and whether what it does in helping the environment is outweighed by its impact on the same.

How AI can help companies fight climate change

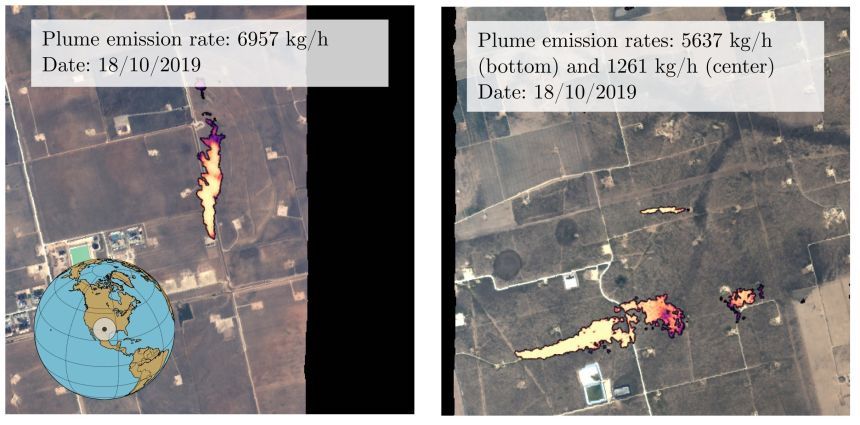

Just this week, researchers developed a tool to detect methane plumes on the Earth from its orbit via machine learning, which could “help identify excessive ‘super emitters’ of methane” and enable more effective action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions”.

It’s just the latest AI-led tool aiming to help people and businesses better understand their impact on the climate, and how they can address it. The UN Environment Programme has also hailed this ability of AI systems, using the tech to monitor air quality, mitigate methane emissions, and reduce the overall emissions of the information and communications tech sector.

AI models can help mitigate climate change in a host of different ways. For instance, they can detect floods or deforestation in real time, analyse crop imagery to find pest or disease problems and perform tasks humans may not be able to – like collecting data from the Arctic when it’s too cold or conducting research in oceans.

“The ways AI can help with climate change are infinite,” Noa Weiss, an AI and machine learning consultant specialising in alternative proteins, tells Green Queen. “At the end of the day, AI is a tool: as long as you have the data, it can help you achieve your goals faster and more efficiently, almost regardless of the goals themselves.”

“This could be either directly (for example, using image recognition models to provide more precise treatments for crops, which translates to less land and water required for producing food), or indirectly (a trivial example: the developers of a climate tech startup using the AI assistant GitHub CoPilot for their coding, which helps them launch their product faster).”

In Weiss’s field of alt-protein, the “most obvious example is using AI to improve the R&D phase, getting better results with less time and resources” – which she does through her non-profit venture, GreenProtein AI. “Getting us to better, cheaper foods that are not animal-based is a big way AI can help mitigate climate change, but it can be even simpler: using models to better plan public transport, for instance, in order to reduce the use of private cars,” she says. “It’s really all about the goal you set.”

Scientists can also use AI to enhance climate pattern modelling, while other applications include identifying how to conserve water, fight wildfires, recover recyclables, and reduce business emissions.

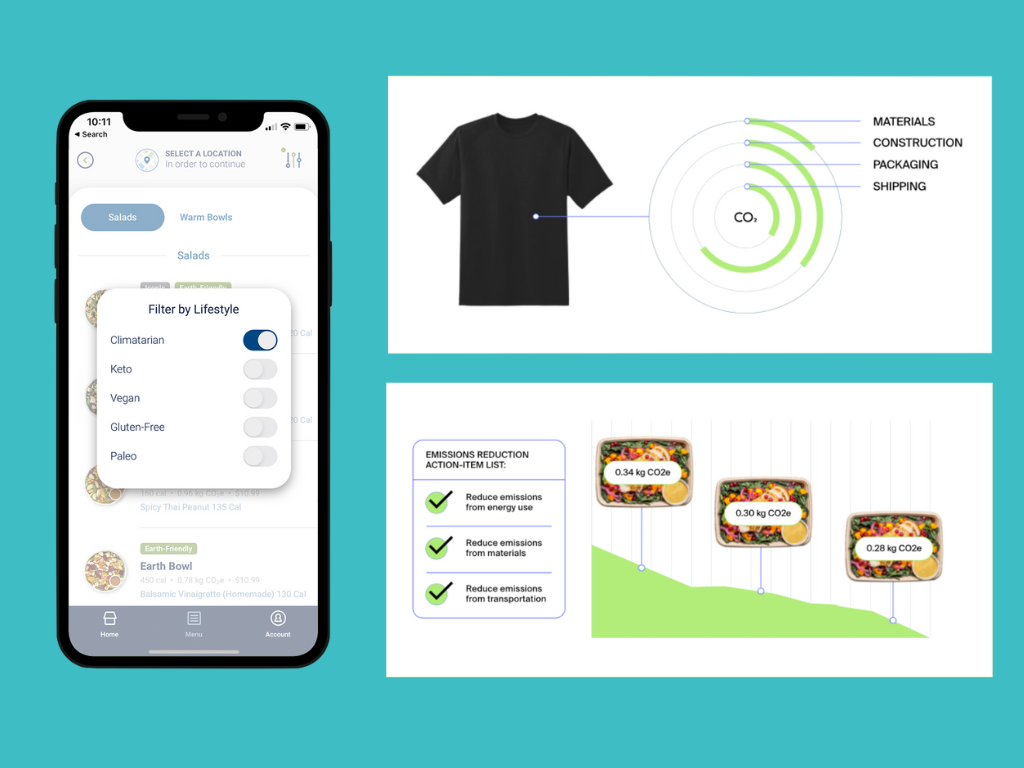

For example, Planet FWD is an emissions calculator that recently launched a platform leveraging AI to tackle food system emissions. It can provide food companies with product-level emissions information in real-time, while wider corporate-level emissions can be revealed in just a few weeks. The tool helps cut carbon modelling costs by at least 82% and accelerates the process by at least 95% for companies looking to decarbonise.

Similarly, Silicon Valley startup ClimateAI employs AI to evaluate how vulnerable crops are to increasing temperatures, using climate, water and soil data to measure how viable growing a certain crop will be in the future.

AI’s large carbon footprint

The flip side to all this, of course, is that AI itself consumes a lot of energy, which, in turn, releases a lot of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. This comes from creating, training, running and using AI’s large language models (LLMs).

Data centres run 24/7, and most use fossil-fuel energy – one estimate puts their contribution to global GHG emissions between 2.5-3.7%. Another estimate predicts that data centres and communication tech are set to account for 14% of global emissions by 2040. With AI models being integrated into search engines, more computing power will be required, which could increase the energy used by five times per search. Plus, the raw materials for the computers AI uses are mined and can carry a hefty environmental cost (not to mention the labour-intensive process).

Then there’s the creation and training of these models. A 2019 study found that making BERT – a generative AI with 110 million parameters (referring to the size of the AI, with more parameters usually meaning more skilled models) – consumed the same amount of energy as a transcontinental round-trip flight for one person.

Creating the much larger GPT-3 – the model ChatGPT is trained on and one that contains 175 billion parameters – used 1,287 megawatt hours of electricity and generated 552 tonnes of CO2. That’s equal to 123 gas-powered cars driven for one year.

As for training AI models, researchers have found that the training process for a single one of these can emit over 626,000 lbs of CO2 – that’s the same as 62.6 cars a year. Another study (not peer-reviewed) has suggested that training GPT-3 could have potentially consumed 700,000 litres of fresh water, which is nearly as much as 5,000 people’s daily water use in the UK.

ChatGPT’s annual carbon footprint is calculated to be 8.4 tons – but since its knowledge cutoff is 2021, it means updating this would need more training, and hence generate more emissions. Another estimate suggests that ChatGPT’s electricity consumption may be between 0.0017 and 0.0026 kilowatts per query – the chatbot sees over 1.5 billion visits per month.

But given the mass usage of AI systems, is their climate impact overstated? Weiss thinks so, if only because these emissions are “the results of the training phase of extremely large-scale models – a rather rare (and expensive) occurrence”. She explains: “In the grand scheme of things, when trying to reduce our negative environmental impact, it makes more sense to focus on those actions and practices our society takes every day (the manufacturing of animal-based foods is one such example), as those quickly aggregate to much bigger numbers.”

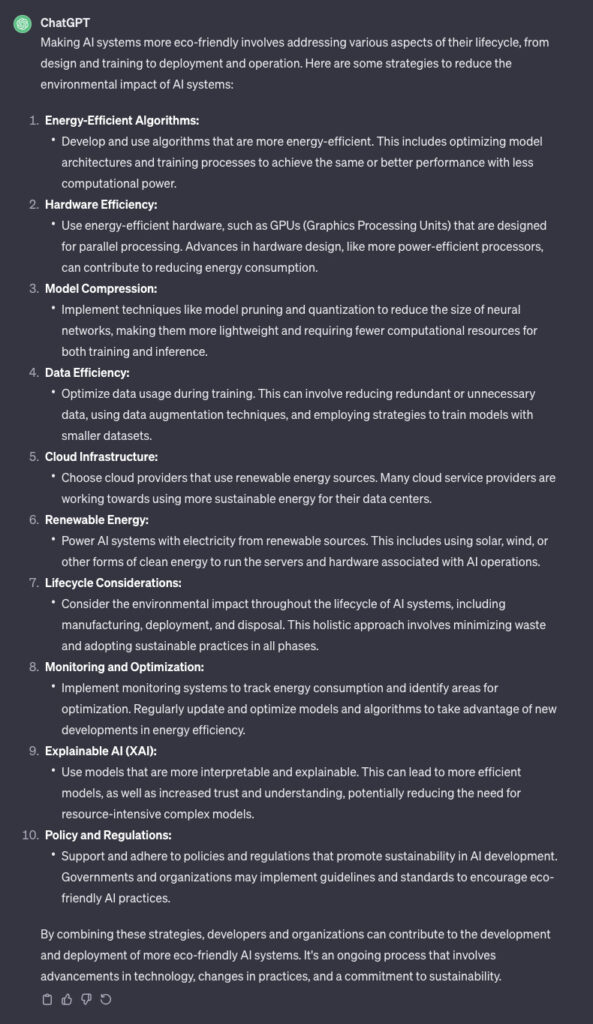

I’ll let ChatGPT spell it out for you. “I don’t have a physical existence or activities, so I don’t have a carbon footprint,” the chatbot wrote when I asked it about its climate footprint. Pressed a little more about the wider impact of the AI industry, it said: “The carbon footprint of AI systems can vary widely depending on factors such as the computational resources used, the energy efficiency of the hardware, and the nature of the tasks being performed. Training large AI models, especially deep learning models, can be computationally intensive and require significant amounts of energy.”

A greener AI system

So where do we go from here? AI is only set to become bigger. And the bigger it becomes, the higher its impact on the planet. In an environment (pun unintended) where we’ve already broached a 2°C temperature rise above pre-industrial levels – let alone 1.5°C – and are heading for 3°C, the climate impact of these technologies must be lightened as quickly as possible.

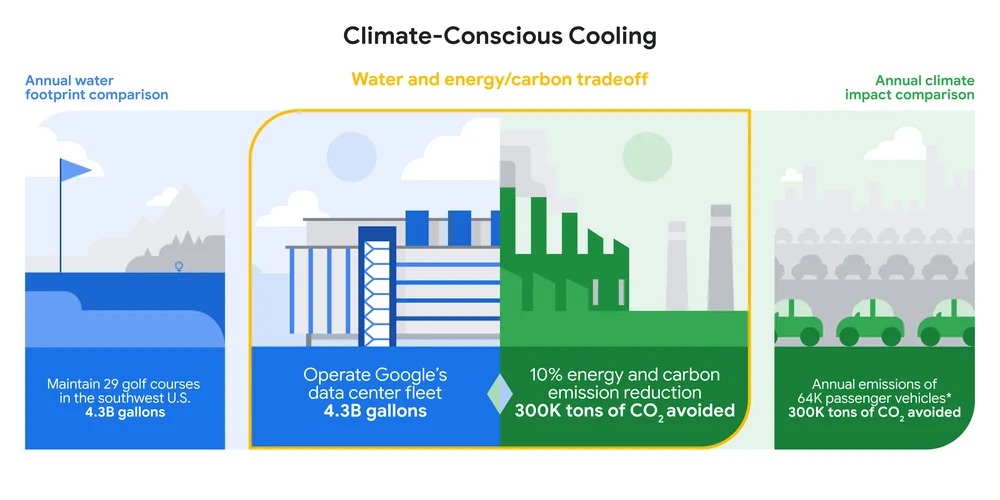

One way to address this can be through data centres. Google research found that data centres cooled using water energy emit about 10% lower carbon emissions than air cooling – the company already runs its offices and data centres (including those for its Bard AI model) on 100% renewable energy. Similarly, Microsoft says all major cloud data providers plan to run data centres on 100% carbon-free energy by 2030, while itself committing to running on 100% renewable power by 2025.

Companies like Altman’s Open AI, meanwhile, could take a leaf out of Hugging Face’s book. The French startup’s language learning model BLOOM – which has 176 billion parameters (more than GPT-3) – consumed 433 MWh of electricity for its training, which is about 25 metric tons of CO2e in emissions (that’s 20 times less than GPT-3).

This figure doubled after taking into account the emissions produced by the equipment manufacturing, infrastructure, and the power needed to run BLOOM – but that’s still much less than its counterparts, thanks to the use of mostly nuclear energy for its training, which doesn’t produce CO2 emissions.

Some have called for greater transparency in this space. It’s important to standardise how carbon footprints are calculated for AI systems. One group of researchers has built a tracker to calculate energy use and carbon emissions from AI training, while Microsoft’s Emissions Impact Dashboard for Azure lets users measure their cloud’s carbon footprint.

“By placing [AI systems’] achievements in proper context and acknowledging the trade-offs involved, we can actively encourage new avenues of research that do not solely depend on developing larger and more complex models,” writes Earth.org author Sophie McLean. “This approach not only promotes responsible practices in the field of AI but also paves the way for ‘greener’ AI.”

Weiss touches upon the cost aspect, explaining: “As training these huge models is a very expensive feat, and the environmental impact pretty much correlates with the monetary cost, I assume the companies that train them also consider that a priority, and hopefully apply such methods when they are available.”

There’s a meta solution involved here too: using AI to solve AI’s problems. As Renee Cho, author at Columbia Climate School’s news site State of the Planet, explains: “AI systems can even green themselves by finding ways to make data centres more energy-efficient. Google uses artificial intelligence to predict how different combinations of actions affect energy consumption in its data centres and then implements the ones that best reduce energy consumption while maintaining safety.”

The AI industry’s carbon footprints reflect the broader issue with the tech sector as a whole, which is already responsible for 2-3% of all emissions. Touching upon that meta aspect, I asked ChatGPT to come up with solutions as well – and come up it did. It added: “It’s important to note that the carbon footprint of AI is just one aspect of the broader environmental impact of technology. The development, manufacturing, and disposal of hardware also contribute to the overall environmental footprint of AI systems.”