Food is Medicine Series: How to Save American Lives and Billions of Dollars with Food Prescriptions

7 Mins Read

Food is Medicine programmes – which include medically-tailored meal initiatives and produce prescription campaigns – could help reduce diseases, improve quality of life, and cut billions in healthcare costs in the US, according to a new study.

This article is the second installment of our Food is Medicine content mini-series.

Poor nutrition is the leading driver of conditions that lead to death and disability in the US, a country that sees 10,000 deaths each week and $1.1T in annual healthcare spending. It’s characterised by some grave numbers. One in two Americans have type 2 diabetes or prediabetes, three-quarters are overweight or obese – with the latter making up 42% of the population – and 14 in 15 have suboptimal cardiometabolic health.

On the whole, rates of diet-related chronic disease in the US are high. This is complemented by the fact that 13.2 million American households (10.2% of the total) were food insecure at some point during 2021. Americans with food insecurity are estimated to spend an extra $1,800 on healthcare per year.

What is Food is Medicine?

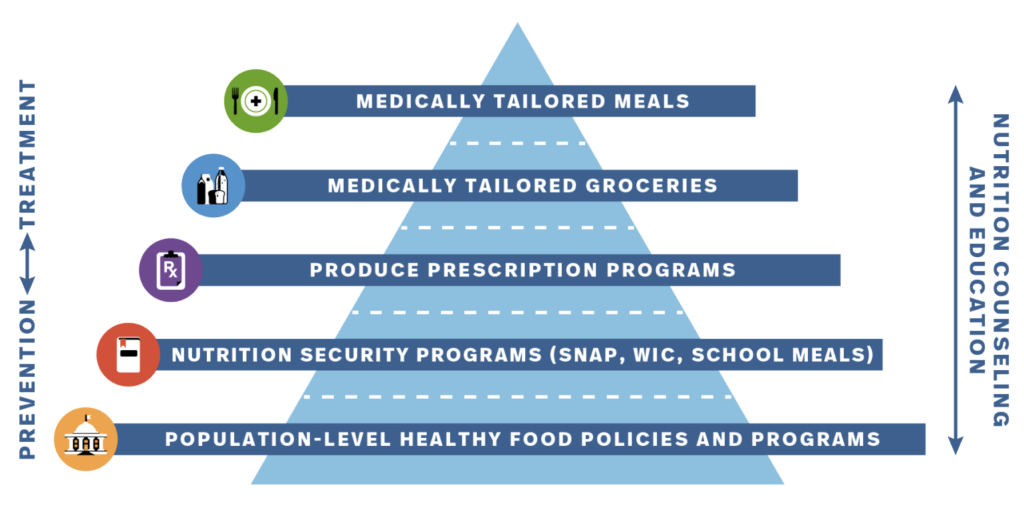

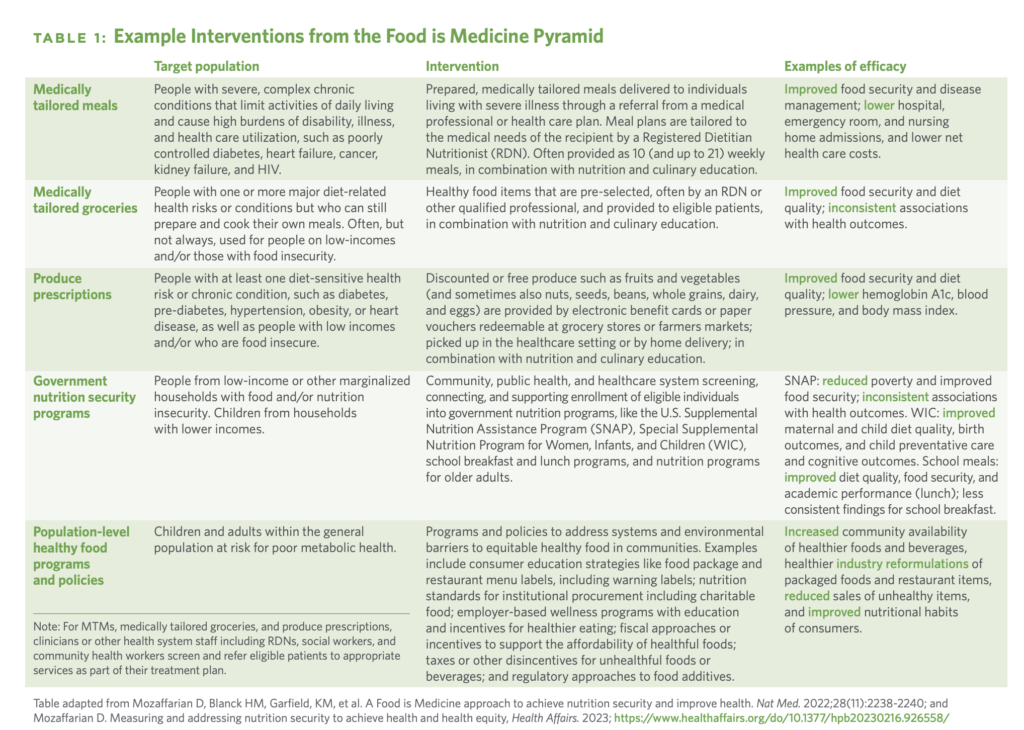

One solution to these growing health issues? Food is Medicine (FIM) (also known as Food As Medicine) programmes. A new report measuring their true cost by researchers at Massachusetts-based Tufts University’s Food is Medicine Institute describes them as “food-based nutritional interventions that aim to treat or prevent disease, show tremendous promise for improving nutrition, reducing food insecurity, improving health outcomes and increasing health equity”.

The Biden administration’s National Strategy on Hunger, Health and Nutrition includes several FIM interventions and has generated support from multiple organisations that have committed to support such efforts. The American Heart Association and the Rockefeller Foundation have earmarked $250M to build a national Food is Medicine research initiative, while insurer Kaiser Permanente has committed $50M to programmes that increase food and nutrition security and improve health outcomes, among other initiatives.

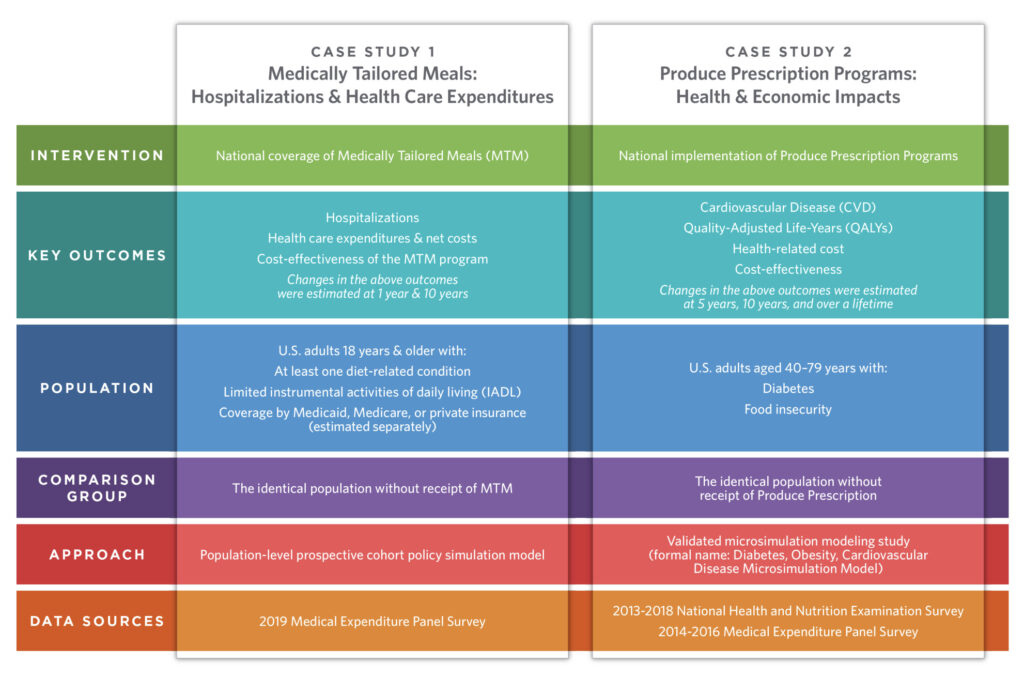

The Tufts University researchers analysed the impact of FIM programmes through two case studies, one evaluating medically tailored meals (MTMs), which help people with specific dietary needs based on their medical conditions, and produce prescriptions, which aim to improve people’s health and food security.

The impact of medically tailored meals

Based on the researchers’ estimates, 6.3 million US adults would be eligible for MTMs. And if these individuals received MTMs, it would help avert 1.6 million hospitalisations and – after factoring in Medicaid and Medicare payments – save $13.6B in healthcare costs. And that’s just in the first year.

If implemented nationally over 10 years, it would save $484.5B in healthcare costs – from an insurer perspective, that’s a net cost saving of $185.1B – and avoid 18 million hospitalisations. But if you include people who are food insecure – who are younger and more likely to be Hispanic or non-Hispanic Black and have lower household income – the number of eligible participants for MTMs reduces to 1.9 million, with net savings of $5.5B.

“Few – if any – other interventions in healthcare are both cost-saving and cost-effective,” the study says. Vaccines and contraception can be cost-saving, for example, but measures like blood pressure and cholesterol screening and control or cancer screening don’t save money, despite being highly cost-effective. “In contrast, MTMs are estimated to gain health and save money – a rare outcome in medical care.”

The impact of produce prescriptions

Based on national data, 6.5 million adults could be eligible for fruit and vegetable prescription programmes. Participants received a $42 credit per month, and used an average of $32 (after subtracting unused vouchers).

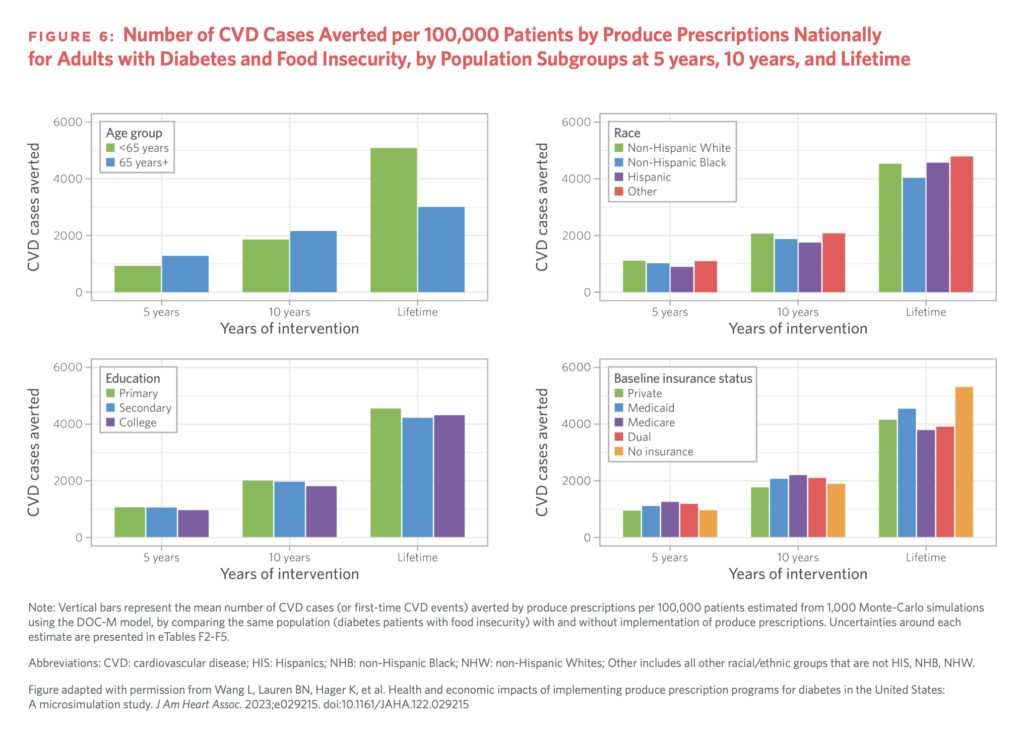

The study found that a national implementation of produce prescription initiatives could prevent 292,000 cardiovascular events and generate 260,000 quality-adjusted life years – a measure of how well a treatment lengthens or improves patients’ lives – over a lifetime.

In a five-year period, they would avert 66,900 cardiovascular events, and produce 126,000 life years. The programme in the case study had better results among people under 65, and among non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic patients (compared to non-Hispanic White patients and other races or ethnicities).

In terms of costs, the implementation would save $39.6B in healthcare costs and $4.77B in productivity costs over a lifetime. In addition, the intervention would be cost-effective at shorter time horizons of five and 10 years.

“Compared to modern weight loss medications, produce prescriptions are much more cost-effective,” the researchers wrote. “The estimated ICER [incremental cost-effectiveness ratio] for weight loss medications is about $200,000 [per quality-adjusted life year], which equates to more than 10 times higher cost per health gained than produce prescriptions.”

Last month, separate research found that people on produce prescriptions ate 30% more fruits and vegetables per day, and witnessed a drop in blood sugar, body mass index and blood pressure. Additionally, they saw the odds of food insecurity – which is linked with chronic health conditions – reduce by a third.

Food is Medicine: policy recommendations

The researchers said that policy solutions can help facilitate and leverage the potential of FIM interventions to improve health and save medical costs for Americans.

There are three key pillars. The first focuses on infrastructure development, with the authors suggesting a flexible anti-kickback statute safe harbour specifically for FIM initiatives, or at least a clarification of the circumstances in which FIM programmes won’t be sanctioned. They added that a comprehensive set of Food is Medicine Networks or Centers of Excellence could be developed, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services could support efforts to develop electronic data infrastructure for food and nutrition insecurity.

Finally, healthcare, advocacy and policy stakeholders could ensure nutrition education for doctors. This could be done via reform of accreditation requirements, medical licensing exams, speciality certifications, and nutrition-centric research programmes.

The second pillar concerns the generation of opportunities and funding. Pilot programmes for MTMs and produce prescriptions could be conducted to provide individuals with support from insurance and government services. States could apply for waivers of Section 1115, which would help deliver FIM programmes to those who need them (nine states have already been granted these waivers). Additionally, private insurance payers and providers could be convened to discuss incorporating FIM interventions into health insurance plans.

Finally, the third pillar focuses on the USDA’s nutrition programmes. Researchers said that while the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) – formerly the Food Stamp Program – has been “successful in reducing food insecurity”, it needs to be leveraged more effectively to reduce nutrition insecurity. This could mean regular analysis and reporting on SNAP purchasing nationally, as well as an encouragement of state pilots testing approaches to advance food and nutrition security.

Additionally, the Gus Schumacher Nutrition Incentive Program (GusNIP) – which provides grants for produce prescription programmes – could be expanded to reach more SNAP participants. including in online retail; and encouragement of innovative state pilots to test new approaches to jointly advance food and nutrition security. And GusNIP’s existing $500,000 limit award per grant could be beefed up to $1M to support larger-scale projects.

Further research is key

The researchers stressed that continued evaluation is key. Areas that research could focus on include potential health and financial benefits for patients, caregivers, family members or households, and economic advantages for local, regional and national farms, retailers and associated supply chain stakeholders.

Further analysis could also look into an integration of FIM programmes with procurement priorities like the support of small and mid-sized farms, local and regional production, regenerative and organic agriculture, fair labour practices and food sector ownership from traditionally marginalised communities. Payers’ experiences in the implementation of FIM initiatives, their identification of barriers to their expansion, and patient experiences can be examined too.

“Food is Medicine interventions have emerged as a highly promising strategy for changing the status quo of US healthcare by placing a stronger emphasis on providing nourishing food as a specific intervention for treating and preventing diet-related chronic disease,” concluded the study.

The report’s senior author Dariush Mozaffarian, a cardiologist and director of the Food is Medicine Institute, said it demonstrates how FIM interventions like MTMs and produce prescriptions can combine with nutrition education for medical professionals and insurance coverage of nutrition counselling to make a real difference in Americans’ health and medical spending.

Devon Klatell, VP of food initiatives at the Rockefeller Foundation, which supported the study, added: “The true costs of our food system – the environmental impact of how food is produced, the working conditions of the people who grow our food, and the impacts on our health, healthcare spending, and health equity are too often left off the price tag.

“This report can assist governments, companies and consumers in better evaluating the value of Food is Medicine interventions by considering not just the price paid for food, but the return on investment in improved health outcomes they can deliver.”

Don’t miss part one of our Food is Medicine series: Can Produce Prescription Programmes Improve America’s Health & Food Security?